The first time I saw Martin Armiger was onstage at Meadows Technicolour Fair on Saturday 29 January 1972. Meadows, on the Fleurieu Peninsula south of Adelaide was South Australia’s second pop festival, after 1971’s Myponga, and Martin’s band Toads, Nightly opened the event.

Martin moved to Melbourne shortly afterwards and fell fruitfully into the Carlton band, drama and poetry scene captured so vividly in Helen Garner’s Monkey Grip. The first time I met him was when The High Rise Bombers, the band he formed with Paul Kelly and Keith Shadwick, came to play in Adelaide in June 1978, shortly after Roadrunner started. He joined The Sports a few months later. The last time I saw him was again on stage, with The Sports at Sydney’s Taronga Zoo on 28 January 2017. After celebrating his 70th birthday earlier this year, he died in France on 27 November.

I interviewed Martin a number of times for Roadrunner after he joined The Sports. We were friendly, in the way that musicians often are with writers who like their band, and I always found him smart, sharp and amusing.

The Sports broke up at the end of 1981. Martin moved to Sydney and landed a gig as music director of Sweet and Sour, an ABC TV series about a young band trying to make it. The music featured in the series involved a who’s who of the Australian music industry and earned him the Best Producer gong at the 1984 Countdown Music and Video Awards. In a rather sad coincidence, those awards were hosted by Mental as Anything’s Greedy Smith, who also passed away in the last few weeks.

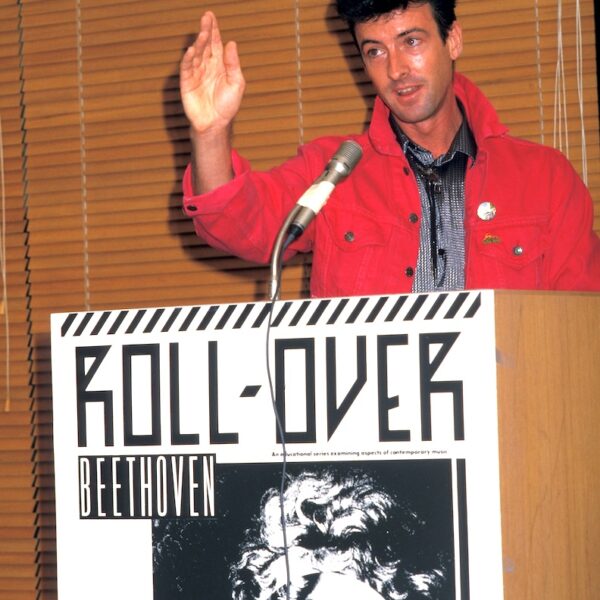

When I was editing the 1987 music education series Roll Over Beethoven for Fairfax Magazines, I commissioned an article from Martin on The Band as part of the section on The Music Industry. Taking time out from composing the music for Young Einstein (winner of the Best Original Music Score at the 1986 AFI Awards), he delivered the following piece. I remember being deeply impressed. As the bell tolls on more and more of those who illuminated the glory years of Australian post-punk and pub rock, Martin’s account is still up there with the best I’ve read about what it was really like inside the band bubbles in those heady times.

∗ ∗ ∗ ∗ ∗

The Band

by Martin Armiger

Once there were not bands. There were artists and artistes and there were big bands. But the band as we know and love it is a fairly recent phenomenon. It combines songwriters, backing musicians, a singer or singers, stylists and conceptualists in the one economical package.

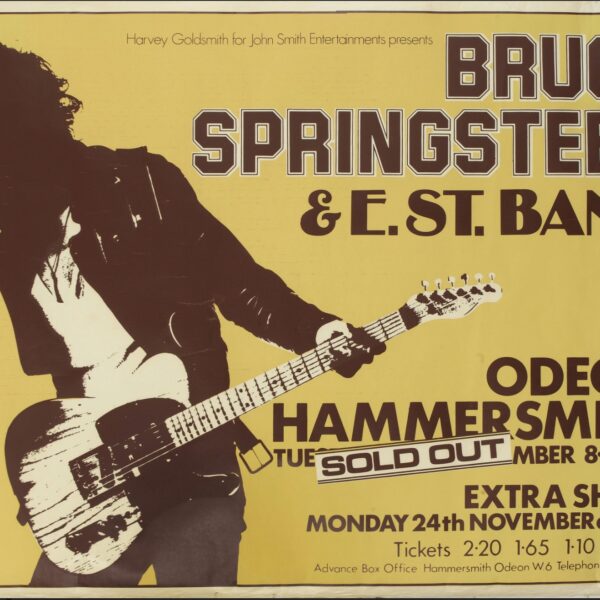

It became the dominant model for the music industry in the 1960s following the success of those two British supergroups, The Beatles and The Rolling Stones. These boys were not mere pawns in the grip of powerful agents, as many pop singers before them had appeared to be. They seemed to control their own destinies. And by amplifying a couple of guitars these four-piece and five-piece groups managed to make a bigger sound than those huge orchestras of the previous era. The sound economic sense of paying four people rather than thirty appealed to the collectivist spirit of the times. The band, as an idea, took off.

A band is a strange kind of cross between a street gang and a small business. At first the ‘gang’ characteristics predominate. You start off playing with a few mates at lunch time or after school. You learn a few Lou Reed tunes or Prince licks and pretty soon you’re not just messing around any more. You feel violently for or against certain radio stations. You probably have a book with a list of possible band names in it. You choose the best name and spray paint it on the nearest bridge. It looks good. You start writing your own songs. Things are getting serious. You want to go out and gig. Everything in your life begins to look pale in comparison to music. Suddenly the realisation dawns: You are a band.

A band is a strange kind of cross between a street gang and a small business.

When a band begins, the members are all outsiders, united by the fact that while they are different from everyone else who is not in a band, they are not yet part of the music industry. They have a lot to prove; to the agents, record companies, would-be-managers etc., to all the people who control the industry. The young band has to convince the cynical world that they, rather than the band up the street, have THAT CERTAIN SOMETHING; that combination of musical ability, teen-appeal, ambition, organizational skills, staying -power, and ‘charisma’, that will make it worthwhile for the industry to invest time and money in promoting the band. Because no band can make it on their own. It needs the support of a vast number of backroom boys and girls to get off the street and onto the charts.

This feeling of ‘outsiderness’ encourages the band to think of itself as an exclusive and tough club for desperadoes. The young band is all for one and one for all; a secret brotherhood (or sisterhood) united by musical tastes and mutual reliance. You start off with a couple of fans; (your brother, your roadie, your girlfriend) and before you know it, armed only with a few songs, a Stratocaster and a leather jacket, you have to face hostile crowds in some huge hotel in Blacktown or Waverly, playing a half-hour set in a tiny space on the stage left you by the main group, to audiences who are not yet warmed up by alcohol.

These are tough times. This is the moment when the old feeling of solidarity might become threatened by the pressure to succeed. The drummer whom you have known all your life may happen to have a unique and eccentric sense of timing. Pub crowds hate nothing more than an erratic beat. (Bye Bye Rocky.) Or maybe the keyboard player (who you love like your mother) can’t get her fingers around some of the chops, or is always late for rehearsal. Perhaps half the presets don’t work on her Yamaha DX7, and there happens to be some snotty kid with a brand new Kurtzweil standing by the side of the stage at every gig, and you know he would just love to join the act. (Bye Bye Sheila.) Now some bands will stick to their eccentricities, even make a fetish of them, and tell the world to go fish. For some this courage will pay off. These bands are very few and far between.

Of course as soon as a manager gets involved he or she will be full of suggestions as to how to improve the product (i.e. your band). Somebody doesn’t look right. Someone else seems to get drunk just by looking at a can of 2.2. Pretty soon, if you let ambition and other people’s advice take over, you might find yourself touring Queensland with a bunch of session players and people you don’t know very well. “What happened to the idea of the band?” you ask yourself. “What happened to my old mates whom I shafted so ruthlessly?” Not to worry. They’re all in other bands already, playing to huge crowds in the little hotel where you all got started, and making a fortune. A band is a gamble. You are going to invest a lot of time in it (and think of all the money that you could have earned elsewhere). If you don’t believe in the people you are working with you might as well get out and start again.

Some bands will stick to their eccentricities, even make a fetish of them, and tell the world to go fish. For some this courage will pay off. These bands are very few and far between.

One reason why it is important to like the people you play with is that you spend so much time together. It takes at least ten hours to travel by car from Melbourne to Sydney or from practically anywhere to anywhere in Australia. You have to like each other’s company. Then when you get where you’re going you are pretty well isolated in your motel room. The only persons outside the band that you get to talk to are DJs from the local radio station or publicity people from the record company. Now these are always splendid chaps, but they are not widely known for their stimulating company. Maybe that’s why musicians are always keen to meet people and make friends after the gig. It also explains why the various band members adopt different roles within the band. One becomes the clown. Another acts the animal. Another is more serious, worries about rehearsals and key changes in songs, and usually stops you getting lost on the way to some obscure gig. One band member will be so obsessed with personal style and dreams of global ambition that he or she can barely communicate with ordinary mortals. This person is probably the singer.

Perhaps your musical ideas are so developed (or so strange) that you think that the only way to realise your true potential is to dispense with other musicians and create the band by yourself. Plenty of artists: have made great solo records. Now the technical development of music-making machines has meant that by using drum machines, polyphonic synthesisers, and all the techniques of the recording ·studio applied to the stage (like having backing vocalists on tape, for ex-ample) you could actually tour as a band entirely alone. Many bands are, in fact, only two·people. (The Eurythmics, among others, make a band look more like a marriage than a gang). Recently Matt Johnson invented a band called The The consisting only of himself. It’s a good way of getting exactly what you want, musically speaking. What seems to happen though, is that eventually these magicians of the studio get tired of their own company and start playing with other musicians again, just for the fun of it. And maybe the manager will suggest that the audience might like something else to look at besides your gorgeous self and a bunch of machines.

One band member will be so obsessed with personal style and dreams of global ambition that he or she can barely communicate with ordinary mortals. This person is probably the singer.

Gradually the little unit known as the band becomes larger. Apart from your manager, who may or may not travel with you, there is the tour manager, and three or four roadies. These chaps become more important to you than food. They lug, they light, they mix, they change broken strings, they give you more foldback, they even get you drinks after the show if the crowd is looking hostile; they are a buffer between you and the world. You love each of them like a brother. Then one day you realise that you pay each one of them about twice as much as you pay yourselves.

In fact when you add up what you are shelling out on the truck hire, lighting rig hire, PA hire, travel, hotels and wages, you discover that you have become a business with a turnover somewhere between that of a small grocery store and a third world country. Perhaps some cost rationalisation will be called for. Perhaps you will stop paying the crew when you are off the road for a few days. You may even feel like sacking the manager and thus saving his massive 20 per cent commission. Please don’t do this, unless you have another, better manager waiting to take over. You really have enough to do writing songs, rehearsing, playing and promoting yourselves without having to worry about making sure everyone else gets paid. Managers are something of a necessary evil. When choosing one, remember this: In a world full of sharks it helps to have the biggest shark on your side.

Your band is a business. After you have registered the name, you will probably register yourselves as a company, with the band members as equal partners (co-directors of the company). You have the legal responsibilities of any company towards its creditors. You can be sued for non payment of bills or for failing to meet the terms of a contract. This all becomes much more complicated when you enter an agreement with a record company or a music publisher. Because these contracts usually cover the world and last for years it is vital to have strong personal and legal advice. Plenty of musicians have found themselves stymied by a bad contract. But the circumstances can vary so wildly between bands and record companies that it is impossible to say just what makes a good contract as opposed to a bad one.

Managers are something of a necessary evil. When choosing one, remember this: In a world full of sharks it helps to have the biggest shark on your side.

One group might want the record company to pay for everything up front, to choose a record producer, choose the studio, organise overseas deals, and so on. For this attention the band will pay dearly, in terms of percentages and future rights to the material. Another band, if it considers itself in a strong position, might want to pay for their own recording, keeping control over every aspect, then finally lease the finished tapes to the company or companies that offer most percentage points. The lowest band royalty that you could ever get would be around 6 per cent of the retail price of a record, tape or disc, (split between all the members). The most you could ever expect would be around 15 per cent. That’s for a really hot band.

These percentages only refer to the performance rights, (which is what you have granted the record company.) As well there are composition rights (songwriters’ royalties) which are fixed by law at something like 6.5 per cent, again divided between the writers. When you sign with a publishing company you agree to give them a percentage of your songwriting royalties in return for them collecting all the money that is owed you from the various territories, and for them to promote your songs with other artists. You normally give the publishers 20 per cent to 30 per cent, maybe more, depending on how much you expect them to do for you. Naturally, the more records you sell, the more publishers will want the rights to your material, and the more they will pay in advance or in royalties, for the privilege of administering it. The general rule is; hang onto percentage points rather than collect a big advance. The trouble with this rule is that by the time someone gets around to offering you a deal you are generally so broke that you jump at the chance of putting some money in the bank or paying for that new amplifier. Still, cash just gets spent, while points go on earning for years.

The main thing is that you have to feel that everyone who gets involved with the band believes in it. It’s no good having a great contract if the record company doesn’t seem too interested in releasing the record. You might have the biggest, greediest manager in the world but what’s the point if he’s too busy to speak to you? The more successful you are, the more easily these things will fall into place. But you may not have a huge smash with your first release. It takes most groups years to perfect a style. Or, as often happens in Australia, your first release may be top ten, then you can wallow for ages trying to find the formula that made it happen. You will spend many mornings waiting for your unemployment cheque. Your family will get used to you not giving Christmas presents. Your loved one will die of boredom waiting for you to come home. Your friends will write you off while all sorts of weird people (the audience) will claim you as a bosom buddy. Do not give up. Remember what you loved about playing music, and especially about listening to music in the first place. Keep your ears clean and your critical faculties intact. And keep on recording, on your four-track cassette, or in low budget studios, until you get the chance to strut your stuff on the Sony digital multitrack with the Solid State Logic desk. Good ‘demos’ help to make great records. It is all the same process, layering one sound on another to produce the perfect three-minute pop record. When you achieve that irresistible single, the world will not only beat a path to your door. They will break down the door, and drag you, blinking, into the spotlight.

Even if the big smash never comes, there is one undeniable consolation for those who play in bands. For someone, somewhere, you will have been the best band there ever was. Some red-eyed rager will approach you in the street, (you are used to this by now) and through cracked lips will tell you, in a crazed voice that the whole street will hear, “That night you guys played at the Maroubra Seals (or wherever) is the BEST night I ever had in my life.” Such is fame.