A hundred years ago: great John Maclean comes home to the Clyde – part 1

On the morning of Thursday 28 November 1918, the Imperial War Cabinet met at 10 Downing Street in London. Outside the weather was wet and windy and the temperature struggled to reach seven degrees Centigrade. It was the American holiday of Thanksgiving; but Americans were definitely not alone in feeling thankful.

The armistices signed by the Allies on 30 October (with Turkey), 3 November (Austria-Hungary) and 11 November (Germany) had brought hostilities in the Great War to a halt. The German Kaiser Wilhelm II had abdicated and fled to the Netherlands, the Austro-Hungarian Emperor Karl I had relinquished power and while Sultan Mehmet VI still sat shakily on his throne in Constantinople, most of his Ottoman Empire was occupied by Allied forces. Great Britain and its Empire forces, in collaboration with the French and Americans had won the war. Thoughts now turned to the peace.

The British King, George V and his two sons, the Prince of Wales and Prince Albert, having crossed the English Channel on H.M.S. Broke the day before, awoke that morning in northern France, en route to Paris. It was a visit that would be ‘a fitting prelude to the great Peace Conference which is shortly to focus the eyes of the world on Paris.’

On the continent of Europe, the collapse of the monarchies in Germany and Austria-Hungary had emboldened socialists and social democrats to seek to construct new social orders, while the upper classes scrabbled to retain at least a share of power. In Germany a revolution resulted in the establishment of a republic on 9 November with the moderate leader of the Social Democratic Party, Friedrich Ebert as Chancellor. German Austria, Hungary and Czechoslovakia also became republics during the month.

The previous evening in Moscow, Lenin had addressed a Moscow party workers meeting. ‘Our job is to wage a desperate struggle against British and American imperialism. It is trying to throttle us as fast as possible in the hope of dealing first with the Russian Bolsheviks, and then with its own.’

Under the leadership of Lenin, the Bolsheviks had been in government in Russia for just over twelve months. Russia had withdrawn from the war by means of the treaty of Brest-Litovsk in March 1918, but civil war was raging as the Red Army grimly battled on a number of fronts against anti-Bolshevik groups. These groups, collectively known as the Whites, were being supported by British, French, American, Canadian, Italian, Serbian, Czechoslovak and Japanese troops. To eliminate a rallying point for the counter-revolutionary forces, the Tsar and his family had been executed in July.

The previous evening in Moscow, Lenin had addressed a Moscow party workers meeting. ‘The German revolution is developing the same way as ours, but at a faster pace,’ he said. ‘In any case, our job is to wage a desperate struggle against British and American imperialism. Just because it feels that Bolshevism has become a world force, it is trying to throttle us as fast as possible in the hope of dealing first with the Russian Bolsheviks, and then with its own.’

Candidates were out on the stump across the British Isles for the first general election since 1910. On 14 November, Andrew Bonar Law, leader of the Conservative Party, had told the House of Commons the Prime Minister David Lloyd George would recommend that the King issue a proclamation summoning a new parliament on 25 November. Nominations would be due on 4 December and an election would be held on 14 December.

Despite the efforts of Lloyd George, Bonar Law and the Parliamentary Labour Party, the grand coalition that had prevailed in the parliament during the war had splintered. At its conference in June 1918, the Labour Party had decided to run an independent campaign while the Liberal Party split into those following Lloyd George and those supporting the former Prime Minister Herbert Asquith. Lloyd George and Bonar Law, having agreed to continue the coalition, endorsed a number of candidates as Coalition candidates. Asquith disparagingly called the letter of endorsement signed by both of them and sent to candidates on 20 November a ‘coupon’, and the election later came to be called the coupon election.

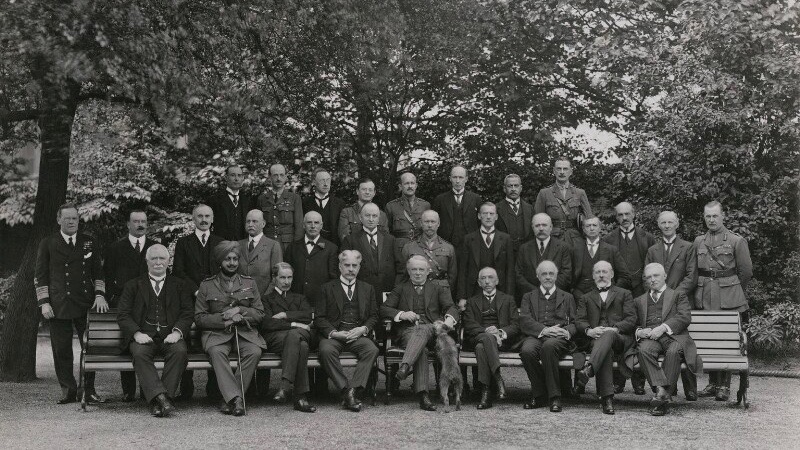

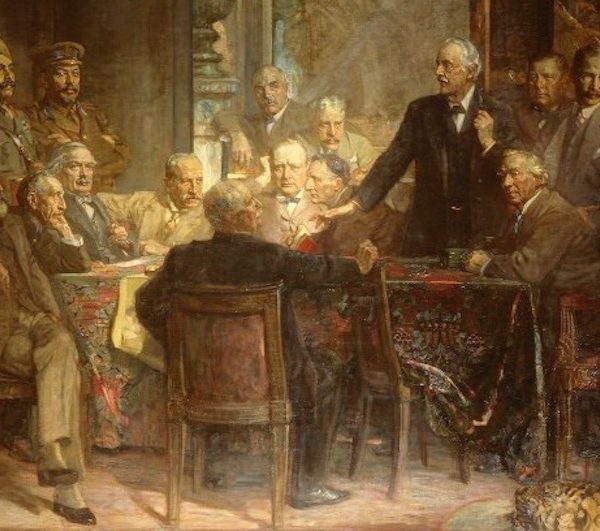

At the 28 November War Cabinet meeting, British Prime Minister Lloyd George was joined around the cabinet table by eleven British cabinet ministers, Canadian Prime Minister Sir Robert Borden and his trade minister Sir G E Foster, Australian Prime Minister Billy Hughes and his navy minister Sir J Cook and the South African defence minister Lieutenant-General Jan Smuts. General Sir H Wilson, Chief of the Imperial General Staff, Rear-Admiral S Fremantle, Deputy Chief of the Naval Staff and the Earl of Reading, British High Commissioner to the United States were also in attendance.

The first two agenda items for the meeting concerned international matters. The first was whether it was legally possible to prosecute the ex-Kaiser for war crimes, in particular the unprovoked invasion of Belgium in 1914 and the launch of submarine warfare against passenger ships. The second concerned a potential disagreement with the Americans about arrangements for the supply of food to Europe.

The third and final item was a domestic matter. The imprisonment of Scottish Marxist John Maclean, Consul for the Russian Republic at Glasgow and a member of the Executive Committee of the British Socialist Party.

George Barnes, the Labour Party representative on the War Cabinet, had placed the matter of Maclean on the agenda. A former general secretary of the Amalgamated Society of Engineers, Barnes had been elected as Labour MP for the Glasgow constituency of Blackfriars and Hutchesontown in 1906. He had been leader of the Labour Party from February 1910 until 1911 and joined the War Cabinet as Minister without Portfolio in August 1917. Barnes disagreed with the Labour Party’s decision to withdraw from the coalition in the coming parliament and in October was disendorsed by his local branch in favour of … John Maclean. Barnes then resigned from the party and decided to contest the election for the newly named seat of Glasgow Gorbals under the banner of Coalition Labour.

The third and final item was a domestic matter. The imprisonment of Scottish Marxist John Maclean, Consul for the Russian Republic at Glasgow and a member of the Executive Committee of the British Socialist Party.

Maclean had been arrested on 15 April 1918 and charged with making statements at meetings in Glasgow, Lanarkshire and Fife between 20 January and 4 April 1918 that were ‘likely to prejudice recruiting and cause mutiny and sedition among the people’. He was convicted of sedition at his trial in Edinburgh in May 1918 and sentenced to five years penal servitude in the notorious Peterhead Prison.

Since that time Barnes had been lobbied forcefully to seek Maclean’s release. And he had personal experience of the strength of feeling in Glasgow. In August he visited the city to give a number of speeches. On 19 August at a meeting of constituents in St Mungo’s Hall, he was forced to abandon the platform after a sustained volley of abuse and interjections from the floor made speaking impossible. One interjector raised the issue of Maclean’s imprisonment. Barnes responded that he would take back to London a report that the majority of the meeting was in favour of Maclean’s release. Many in the crowd cried out ‘Glasgow’. Barnes retorted that he did not accept that that voiced the opinion of the constituents or the workers of Glasgow.

Maclean believed that his food had been doctored during his first stint in prison (April 1916—June 1917) and was determined not to take it during his second sentence. The authorities granted the concession of allowing his meals to be supplied from outside, but attempts by his wife Agnes to organise this in Peterhead during May 1918 proved fruitless and Maclean’s request to be moved to a Glasgow prison where food could be supplied was refused. Maclean then went on hunger strike and from 1 July was forcibly fed twice a day by stomach tube.

Maclean’s request to be moved to a Glasgow prison where food could be supplied was refused. Maclean then went on hunger strike and from 1 July was forcibly fed twice a day by stomach tube.

When Agnes Maclean was allowed her first visit to Peterhead on 22 October she was shocked by her husband’s appearance. She described her visit in a letter to the British Socialist Party.

‘He (John) told me he tried to resist the forcible feeding by mouth tube, but two warders held him down, and that these men never left him thereafter, night or day, till he was forced to give in. I was shocked beyond measure by these statements (made to me in the presence of the prison doctor and two warders) and by the evidence of their truth supplied by his aged and haggard appearance. They contradict entirely the assurances given to me by the authorities that he was in good health.’

The letter was widely published in the Socialist papers and the calls for Maclean’s release grew even louder and more insistent.

A special emergency conference of the Labour Party was held on 14 November at the Central Hall, Westminster to determine the party’s reconstruction policy and whether to withdraw from the coalition government immediately or when a peace treaty was signed. While the votes were being tallied on a motion from the Parliamentary Party to remain in coalition (the motion was defeated), a young man from the gallery shouted, ‘John Maclean is dying in prison. What are you going to do about it? Rascals.’ Considerable noise ensued and it took some time for the Chairman, John McGurk and party Secretary Arthur Henderson to restore order.

At a special emergency conference of the Labour Party held on 14 November, an emergency resolution was submitted demanding the release of John Maclean, ‘who is being tortured in prison’ and all other political prisoners.

Following the adoption of the reconstruction proposals, an emergency resolution was submitted demanding the release of John Maclean, ‘who is being tortured in prison’ and all other political prisoners. In reply to shouts, the Chairman said that conscientious objectors were included. The resolution was carried without discussion and amid cheering. The conference closed with the delegates singing ‘The Red Flag’ as they filed out.

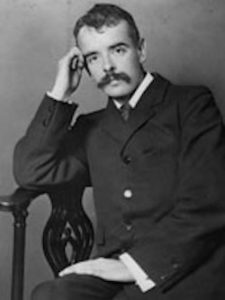

Later that day in the House of Commons, John Howard Whitehouse (pictured right), the Liberal MP for the Scottish constituency of Mid-Lanark queried the Secretary for Scotland, Robert Munro, about the fate of political prisoners, conscientious objectors and Maclean in particular.

‘There are certain special features in the case of Mr Maclean to which I wish to call the attention of the House,’ Whitehouse said. ‘Mr Maclean is a man of high character. He has behind him a great record of honourable work. He has given a great part of his life in the service of teaching, and I do not think I shall be guilty of any great exaggeration if I say that some of the Clauses in the Scottish Education Bill were only made possible through his devoted work in the cause of education. He is a political offender. He received a sentence which I think is excessive, and if it was carried out it would be of a barbarous character and certainly alien to what I believe is the general feeling of the people in this country. Is there any reason why Mr Maclean and the other political prisoners should be kept in prison a moment longer in view of the end of the War? I am going to make an appeal to the Secretary of Scotland in the case of Mr Maclean and I do not base it on the ground that the case is the subject of general agitation. I am going to make my appeal for Mr Maclean on the ground that the War having come to an end a free and generous country has always in the days of peace shown great generosity to men whom it has attacked and repressed during the passions and strain of war.

‘These men have held certain views with great sincerity. They have shown the highest courage when they have preferred to get up against the multitude on behalf of what they believe to be right. I say that these men are of the highest courage and are entitled to our respect. Let me remind the Right Hon. Gentleman the Secretary for Scotland that at the great Labour Conference today, which was so sensational in so many ways, a resolution was passed unanimously and without a single dissentient voice by delegates representing some millions of people demanding the release of Mr Maclean.’

‘My own wish is to pass a night in A’deen with as many old friends as Morrison may be able to scrape together. But remember, absolutely no demonstration in Glasgow. That can be left till after.’

Out of the public eye, Maclean had been informed that moves were afoot for his release. He wrote from Peterhead Prison to his wife on 16 November about his preferred arrangements. He asked her to send him the address of William Morrison of Aberdeen (a friend and a local member of the Socialist Labour Party) and the name and address of the secretary of the Peterhead Trades Council.

‘Unless circumstances dictate otherwise, I would like to spend a night in A’deen with old friends,’ he wrote. ‘You might let the Morrisons know, so as to be prepared for me at any time. Bear in mind, however, that I don’t know when I’ll be released or from which prison, so therefore to prevent silly rumours that might hamper the actions of the Government say nothing about this letter to anyone at all. I am solely guided by the course of events & past history. If freed from here I’ll wire you at once, & if I stay at A’deen, I’ll wire you just before catching the train from A’deen, so that you may be prepared for me at home. My strongest desire is to get right home without anyone waiting for me at the station.

‘Should the Government see fit to let you know some days before I get out, you might let me know before my release whether I should come right home or not. My own wish is to pass a night in A’deen with as many old friends as Morrison may be able to scrape together. But remember, absolutely no demonstration in Glasgow. That can be left till after. I have given assurances of that here already, so that my honour must be considered.’

* * *

Continued in A hundred years ago: great John Maclean comes home to the Clyde—part 2