Thanksgiving

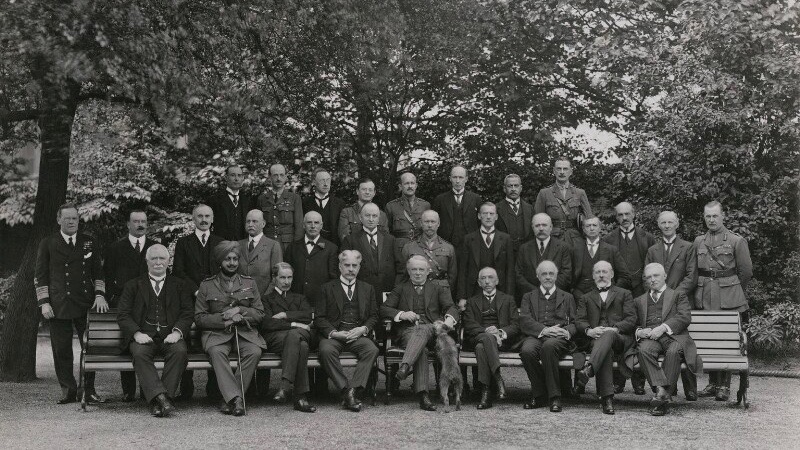

On the morning of Thursday 28 November 1918, the Imperial War Cabinet met at 10 Downing Street in London.

Outside the weather was wet and windy and the temperature struggled to reach seven degrees Celsius. It was the American holiday of Thanksgiving; but Americans were not the only ones feeling thankful.

The armistices signed by the Allies on 30 October (with Turkey), 3 November (Austria-Hungary) and 11 November (Germany) had brought hostilities in the Great War to a halt. The German Kaiser Wilhelm II had abdicated and fled to the Netherlands, the Austro-Hungarian Emperor Karl I had relinquished power and while Sultan Mehmet VI still sat shakily on his throne in Constantinople, most of his Ottoman Empire was occupied by Allied forces. Great Britain and its Empire forces, in collaboration with the French and Americans had won the war. Thoughts now turned to the peace.

The British King, George V and his two sons, the Prince of Wales and Prince Albert, having crossed the English Channel on HMS Broke the day before, awoke that morning in northern France, en route to Paris. It was a visit that would be ‘a fitting prelude to the great Peace Conference which is shortly to focus the eyes of the world on Paris’.

On the continent of Europe, the collapse of the monarchies in Germany and Austria-Hungary had emboldened socialists and social democrats to seek to construct new social orders, while the upper classes scrabbled to retain at least a share of power. In Germany a revolution resulted in the establishment of a republic on 9 November with the moderate leader of the Social Democratic Party, Friedrich Ebert as Chancellor. German Austria, Hungary and Czechoslovakia also became republics during the month.

The previous evening in Moscow, Lenin had addressed a Moscow party workers meeting. ‘Our job is to wage a desperate struggle against British and American imperialism. It is trying to throttle us as fast as possible in the hope of dealing first with the Russian Bolsheviks, and then with its own.’

The Bolsheviks had been in government in Russia for just over twelve months. Russia had withdrawn from the war in March 1918, but civil war was raging as the Red Army grimly battled on a number of fronts against anti-Bolshevik groups. These groups, collectively known as the Whites, were being supported by British, French, American, Canadian, Italian, Serbian, Czechoslovak and Japanese troops. To eliminate a rallying point for the counter-revolutionary forces, the Tsar and his family had been executed in July.

The previous evening in Moscow, Lenin had addressed a Moscow party workers meeting. ‘The German revolution is developing the same way as ours, but at a faster pace,’ he said. ‘In any case, our job is to wage a desperate struggle against British and American imperialism. Just because it feels that Bolshevism has become a world force, it is trying to throttle us as fast as possible in the hope of dealing first with the Russian Bolsheviks, and then with its own.’

Candidates were out on the stump across the British Isles for the first general election since 1910. On 14 November, Andrew Bonar Law, leader of the Conservative Party, had told the House of Commons the Prime Minister David Lloyd George would recommend that the King issue a proclamation summoning a new parliament on 25 November. Nominations would be due on 4 December and an election would be held on 14 December.

Despite the efforts of Lloyd George, Bonar Law and the Parliamentary Labour Party, the grand coalition that had prevailed in the parliament during the war had splintered. At its conference in June 1918, the Labour Party had decided to run an independent campaign while the Liberal Party split into those following Lloyd George and those supporting the former Prime Minister Herbert Asquith. Lloyd George and Bonar Law, having agreed to continue the coalition, endorsed a number of candidates as Coalition candidates. Asquith disparagingly called the letter of endorsement signed by both of them and sent to candidates on 20 November a ‘coupon’, and the election later came to be called the coupon election.

Across the British Isles candidates were out on the stump for the first general election since 1910. Despite the efforts of Prime Minister Lloyd George, Unionist Party leader Bonar Law, and the Parliamentary Labour Party, the grand coalition that had prevailed in the parliament during the war had splintered. The Labour Party had decided to run an independent campaign, while the Liberal Party split into those following Lloyd George and those supporting the former prime minister, Herbert Asquith. Lloyd George and Bonar Law, having agreed to continue the coalition, endorsed a number of coalition candidates. Asquith disparagingly called their letter of endorsement, which was sent to candidates on 20 November, a ‘coupon’; and the election later came to be called the coupon election.

~

On 28 November, Lloyd George was joined around the War Cabinet table by eleven British ministers plus a number of Imperial ministers and other advisors. Canada was represented by Prime Minister Sir Robert Borden and trade minister Sir GE Foster; Australia by Prime Minister Billy Hughes and navy minister Sir J Cook; and South Africa by defence minister Lieutenant-General Jan Smuts. Chief of the Imperial General Staff, General Sir HH Wilson; Deputy Chief of the Naval Staff, Rear-Admiral S Fremantle; and British High Commissioner to the United States, the Earl of Reading; were also in attendance.

After updates on the Western Front and the situation in the Baltic, the next two agenda items concerned international matters. The first was whether it was legally possible to prosecute the ex-kaiser for war crimes; in particular for the unprovoked invasion of Belgium in 1914 and the launch of submarine warfare against passenger ships. The second concerned a potential disagreement with the Americans about arrangements for the supply of food to Europe.

The final item was a domestic matter. The imprisonment of Scottish Marxist John Maclean, consul for the Russian Republic at Glasgow and a member of the executive committee of the British Socialist Party.

George Barnes, the Labour Party representative on the War Cabinet, had placed the matter of Maclean on the agenda. Two days before the meeting, he drafted a memorandum suggesting the Cabinet authorise Maclean’s release, ‘along with any others who might be in like plight for similar offences’. He wrote:

‘The continued agitation about John Maclean constitutes a serious danger for the government. Mass meetings have been held in many places, including London, and resolutions continue to pour in demanding his release.

‘I think that no good purpose is being served by keeping him in prison, and that a favourable opportunity presents itself for his release. I should not take any notice of the agitation but release him as a matter of amnesty in consequence of the signing of the armistice. I note that there is to be a meeting in the Albert Hall next Saturday [30 November], convened by [George] Lansbury and those with whom he is associated, and I have little doubt but that John Maclean will bulk very largely in the speeches. That will no doubt be followed by many similar meetings in the next two to three weeks, with, I think, bad results on the public mind.

‘Mr Munro [secretary for Scotland] has said he would be willing to release Maclean if it was a matter of general amnesty. But the position is that in England and Wales there are no political prisoners convicted, as Maclean is, under D.O.R.A. [the Defence of the Realm Act]. There are only two in Scotland; the other being a tram conductor called Milne, who has served about forty out of a sentence of sixty days.

‘I think it would be an act of grace therefore, to release both of them before the agitation assumes larger and more dangerous dimensions.’

~

Out of the public eye, Maclean had been informed that moves were afoot for his release. On 16 November he wrote from Peterhead Prison to his wife Agnes about his preferred arrangements. He asked her to send him the address of William Morrison of Aberdeen (a friend and a local member of the Socialist Labour Party) and the name and address of the secretary of the Peterhead Trades Council. He continued:

‘Unless circumstances dictate otherwise, I would like to spend a night in A’deen with old friends. You might let the Morrisons know, so as to be prepared for me at any time. Bear in mind, however, that I don’t know when I’ll be released or from which prison, so therefore to prevent silly rumours that might hamper the actions of the Government say nothing about this letter to anyone at all. I am solely guided by the course of events & past history. If freed from here I’ll wire you at once, & if I stay at A’deen, I’ll wire you just before catching the train from A’deen, so that you may be prepared for me at home. My strongest desire is to get right home without anyone waiting for me at the station.

‘Should the Government see fit to let you know some days before I get out, you might let me know before my release whether I should come right home or not. My own wish is to pass a night in A’deen with as many old friends as Morrison may be able to scrape together. But remember, absolutely no demonstration in Glasgow. That can be left till after. I have given assurances of that here already, so that my honour must be considered.’

~

Once the first four items had been dealt with, Lloyd George introduced the final matter on the War Cabinet agenda.

‘The next question concerns the release of a man named John Maclean, who is a Bolshevist. He has a great deal of ability, but has used the whole of this ability to prevent the manufacture of munitions. We had to prosecute him for inciting sedition, and he was sentenced to three years’ penal servitude. We let him out after only thirteen months because the workmen said it would ease things. On his release he again started making seditious speeches, and he was prosecuted once more and is now in gaol. Now exactly the same agitation has started again. He is Mr Barnes’ political opponent, and Mr Barnes thinks it will help him.’

‘I do not base it on that ground,’ Barnes countered. ‘I want to say this, prime minister, that all the forces of opposition to the government are focusing on John Maclean, including not only the Bolshevists, but the Labour Party. They are threatening to do all sorts of things and I am afraid they will put their threats into execution one of these days. For instance, I have heard it whispered that there is on foot some scheme for cutting off the light on the Clyde and Mr George Lansbury has a meeting at the Albert Hall on Saturday and also on Sunday and I know that John Maclean will feature largely in the program there.’

‘Demanding his release?’ asked the Australian Prime Minister Billy Hughes.

‘Yes,’ Barnes replied. ‘I am getting resolutions every day and I suppose every member of parliament is getting the same thing. Meetings are being held all over the country focusing all attention on the release of this man. As far as I remember the Irish objection was to the general release of all prisoners. It was thought at the time that there were a lot of these people, but there are not. There is not a single one in England or Wales; there are only two in Scotland, namely John Maclean and a man named Milne.’

‘Do you propose to let out De Valera?’ asked Hughes.

‘No,’ said Barnes, ‘his case is quite separate from this case and from the case of conscientious objectors.’

‘There is this difference in regard to the release of John Maclean,’ said Lloyd George. ‘John Maclean was imprisoned for using seditious language, but the Sinn Feiners were imprisoned for being engaged in active rebellion. There is no doubt that preparations were in hand for a German invasion of Ireland and the Sinn Feiners were to get rifles and guns. That is rather a different thing to using seditious language.’

‘From the English point of view,’ said the Home Secretary, Viscount Cave, ‘I wish to point out that this man John Maclean is backed by the revolutionary party. I am told that the agitation in his favour in Scotland is rather dying down, but that he is being supported by the revolutionists in South Wales and in London. If you release him, I have no doubt he will be brought to London and South Wales to make speeches and it will be treated as a great triumph for them.’

‘You are against his release?’ Lloyd George asked.

‘Yes,’ Lord Cave replied.

Lloyd George then went around the table. The British Secretary of State for War, Viscount Milner; the Australian Minister of the Navy, Sir Joseph Cook; and the Leader of the House of Lords, Earl Curzon, were also against Maclean’s release. Then he came to Billy Hughes.

‘I favour his release,’ said Hughes. ‘This question is mixed up with politics. I have had to deal with this kind of thing in Australia over and over again and I think it would create a bad precedent in terms of Ireland for this very good reason, that Sinn Fein is now quite distinct from Bolshevism. If they got up at the Albert Hall and asked for the release of De Valera, they would lose 50 per cent of the seats they are trying to get. But this man, John Maclean, has a Scotch name and he is a trade unionist, and I say you will do well to let him out. His voice will be lost in the turmoil of the election if he is outside, but if he is inside, everyone will clamour for his release. If he is out, let him say what he has to say and you will be perfectly safe.’

The Canadian Prime Minister Sir Robert Borden agreed with Hughes. ‘From the point of view of Canada, I am inclined to let him out,’ he said. But his Canadian Minister of Trade and Commerce, Sir George Foster disagreed, saying ‘I think he is a bad man and a condemned criminal and I would keep him there to the end.’

The Earl of Reading, Lieutenant-General Jan Smuts and the First Lord of the Admiralty, Sir Eric Geddes, came down in favour of release while the British Secretary of State for the Colonies, Walter Long, was for keeping him in.

The Chancellor of the Exchequer, Andrew Bonar Law said, ‘From the point of view of Great Britain, I would let him out, but I would not do so until I knew what the effect would be in Ireland.’

The British Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, Arthur Balfour, agreed. ‘Like Mr Bonar Law, I consider myself on the hedge in regard to this question.’

‘I am in favour of letting him out,’ said the British Secretary of State for India, Edwin Montagu. ‘You can let him out this week, but if you wait until after the meeting Mr Barnes talked about, it would be very difficult to do so. We shall probably have to do battle with the revolutionaries in this country sooner or later, but do not let us bring it about over the issue of a miserable creature of this kind.’

‘We agree to let him out,’ said Bonar Law, ‘but we must first send a telegram to the Irish Government to see whether they regard it as dangerous.’

‘I prefer to talk to the lord lieutenant on the telephone about it this afternoon,’ said Walter Long. ‘I know their views, but I do not believe myself that you can let him out and keep Sinn Feiners in.’

‘Then the balance of opinion,’ said Lloyd George, ‘leaving out of account Mr Bonar Law and Mr Balfour, is in favour of letting him out.’

‘As I understand the chancellor of the exchequer’s hedge and my hedge,’ said Balfour, ‘it depends a great deal on the Irish aspect of the question. If the Irish government consider his release makes their position impossible, then I am for keeping him in; but if the Irish government raises no objection, then I do not mind.’

‘It really is a different case,’ said Lloyd George. ‘The Sinn Feiners were imprisoned not merely for making seditious speeches, but for being concerned in an active conspiracy for a rebellion in Ireland against British authority. One man who was arrested had in his pocket a document showing the number of troops that could be brought together when the Germans landed. Then there was another document, if you remember – I think we had it from De Valera – referring to a rebellion in two months from that date. That I put in a totally different category to John Maclean.’

‘The difficulty I see,’ said Bonar Law, ‘is that it will probably be said that we are letting this man out as an act of grace because he is a political prisoner. What will the Irish government say about these other political prisoners who have been put in prison, but not tried?’

‘He has been imprisoned for making seditious speeches, for the good of the country, and the case it quite different,’ said General Smuts.

Nodding in the direction of Walter Long, Lloyd George said, ‘I suggest the colonial secretary, who I am sure will be quite impartial in spite of the fact he takes a strong line one way, should get through to the chief secretary in Dublin and say that the feeling in the Cabinet is that they would like to release John Maclean, but that the foreign secretary, the chancellor of the exchequer and I would like to release him if it did no harm in Ireland. I do not think it is worth having an agitation about a man who does far more harm in prison than outside.’

‘Can I tell the Irish government prime minister, that whatever happens over this man, the Cabinet will support them in keeping the Sinn Feiners in order?’ Long asked.

‘I think you might say that we reached this decision on the grounds that there was a distinction between the two cases, and that John Maclean is not in the same category as the Sinn Feiners,’ Lloyd George replied.

‘Does this apply to the other man?’ George Barnes queried.

‘Yes,’ said Lloyd George, ‘he has practically served his time.’

~

There being no objection from the Irish government, the Secretary for Scotland, Robert Munro authorised the discharge of Charles Milne from custody the following day (Friday 29 November) and Maclean was released from penal servitude on ticket-of-leave on Monday 2 December. The ticket-of–leave was rescinded by means of a King’s pardon later in the month.

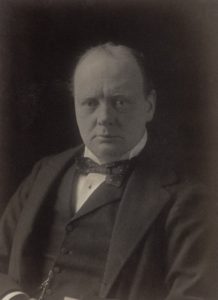

Maclean’s case was certainly a live one on the hustings. On the evening before the War Cabinet meeting, the Coalition Liberal candidate Winston Churchill addressed a meeting at the Kinnard Hall in his Dundee electorate. Lively scenes characterised the gathering, according to the Glasgow Herald.

‘His [Churchill’s] handling of the Bolshevik elements in the hall won the admiration of the vast majority of the audience. “If this country had been full of John Macleans we would have been conquered by the Huns” – that is but one example of many sharp words addressed to the extremists by Mr. Churchill, who reminded them that the strong forces in this country which had enabled us to overcome so many difficulties were not afraid of John Maclean and all his backers.’

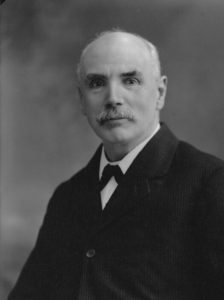

Meanwhile in Edinburgh on the evening of 28 November, the Lord Advocate, James Avon Clyde – Coalition Unionist candidate for the seat of Edinburgh North – addressed a meeting of electors in the Abbeyhill Parish Church Hall. Clyde, the prosecutor at Maclean’s May 1918 trial, was asked if he believed that the introduction of British and Allied troops into Russia was not in the direct interests of British and Allied capitalists. Clyde’s response, the Glasgow Herald reported, was that the suggestion was a gross slander.

‘The idea that we had conducted either in Russia or anywhere else in this war military operations in defence of the interests of a class was a slander. There was not a word of truth in it. Asked if he was in favour of the immediate release of John Maclean, Mr Clyde answered, “Certainly not. I should like to know why a man who did his best to incite his fellow citizens to burn houses, to abolish their institutions and to establish the rule of force in this country is entitled to special consideration? He will get none from me.” (Loud applause.)

‘The Elector – Why were the same steps not taken with Sir Edward Carson?

‘Mr Clyde – Because Sir Edward Carson’s was not a like case. His action was purely political; the other was a direct attempt to upset the social order.’

The Carson case was indeed different from Maclean’s, but not in the way Clyde stated.

In 1892, the prominent Dublin barrister Edward Carson was elected as an Irish Unionist member of parliament for the University of Dublin. He became leader of the Irish Unionist Alliance in 1910 and led its fight against Home Rule – the establishment of a devolved Irish Parliament in Dublin. In 1913, he formed the loyalist paramilitary organisation the Ulster Volunteer Force. When Irish Home Rule seemed inevitable in 1914, he authorised the purchase and smuggling into Ulster of 20,000 rifles and 2,000,000 rounds of ammunition for the UVF. Only the outbreak of the Great War prevented an Irish civil war in 1914.

To smuggle guns and ammunition in preparation for an armed rebellion against an Act of Parliament was obviously considered less serious by the first law officer of Scotland than speaking out about how the existing order oppressed those at the bottom of society.

∗ ∗ ∗ ∗ ∗

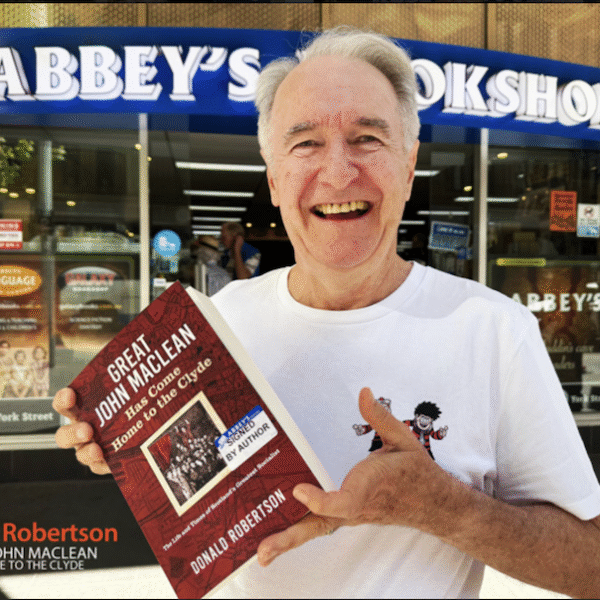

This is chapter 37 of ‘Great John Maclean has come home to the Clyde’, my biography of Scotland’s greatest socialist, published by Resistance Books, London, 2025.

∗ ∗ ∗ ∗ ∗

Featured image: Sir James Guthrie: ‘Statesmen of World War I’ (detail)