‘No Fixed Address’: The Nullarbor crash

It was Easter 1982. No Fixed Address were on the road, driving back east from Perth, heading to Alice Springs.

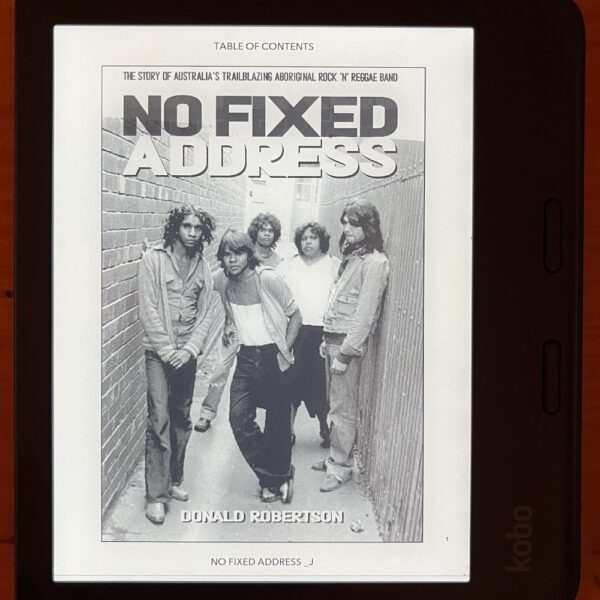

This is the Prologue to No Fixed Address (Hybrid Publishers, 2023).

To purchase a copy, click here

Although they’d been impressing audiences and slowly building a live following in Adelaide, Melbourne and Sydney for a couple of years, the release of the film Wrong Side of the Road the previous November had brought the group to the attention of the national media. A drama about 48 hours in the lives of two Aboriginal bands, No Fixed Address and Us Mob, it had won the Jury Prize at the 1981 Australian Film Institute Awards and had been playing to capacity audiences on the independent film circuit.

Four shows to packed houses on Cold Chisel’s Summer Offensive tour in December 1980 had opened the eyes of No Fixed Address to how big things could be. Supports to Ian Dury and the Blockheads (November 1981) and The Clash (February 1982) had just put the group in front of a whole new audience of Australian punk and new wave music fans. The soundtrack album to Wrong Side of the Road, with six tracks from each of the two featured bands, had received solid airplay on alternative radio across the country and sold well over the summer. They had management in the form of Mick Pacholli, publisher of tagg (the alternative gig guide) magazine; had a music publishing deal with Michael Gudinski’s Mushroom Music; and after signing with hip Melbourne independent label Rough Diamond, had just completed recording tracks for a mini-album. The producer was David Briggs, former guitarist with Little River Band, who was fresh from doing the honours on Australian Crawl’s five-times platinum debut The Boys Light Up. No Fixed Address were a young band that was definitely going places in the Australian music scene. But the difficulties of being young Aboriginals were never far away.

‘We’d had trouble in Perth,’ says guitarist Ricky Harrison. ‘We had about twenty gigs booked and thirteen of them were cancelled when the promoters found out we were an Aboriginal band. Cold Chisel were in town as well and helped us get some gigs.’

‘They got to Perth and I had all these gigs booked,’ says Mick Pacholli. ‘Two grand a gig. And all the Italians over there said, “These are blackfellas – we’re not putting ’em on.”

‘I said, “What didn’t you understand about Australia’s premier Aboriginal rock band? What is wrong with you people?”

‘“We’re not putting them on.”

‘“Well, that’s a big slice of my budget. You’re leaving me stranded.”’

Local promoter Kenn McMillan managed to cobble together enough replacement gigs to cover costs. But the episode – which closely mirrored an incident of discrimination depicted in Wrong Side of the Road – left a sour taste.

The cancellation of the gigs was just the first setback on the trip. While in Perth, drummer Bart Willoughby broke his right arm. While he could still get up on stage to sing, the band’s two recently engaged percussionists, Joe Geia and Billy Inda Cummins, had to cover for the lack of drums. For the final show of the Perth run, which was filmed by ABC-TV’s Rock Arena, local drummer Reg Zar was drafted in.

When the Perth engagements were completed, the touring party loaded up their two cars and equipment truck and set out on the next leg of the tour, to Kalgoorlie. From there it would be the long trek across the Nullarbor Plain to Ceduna, South Australia and then up to Alice Springs. But at 1:30 am on Tuesday, 13 April, on the Eyre Highway 20 kilometres east of Norseman, disaster struck.

‘I was in the lead car, with our roadie Angelo DiCarlo, who was driving,’ recalls Ricky Harrison. ‘His mouth was going a hundred miles an hour. Maxine Briggs was in the back seat. She did our lights. Also back there was Joe Hayes, our bass player and his wife, Jean. Behind us was the truck with the PA and drums and our amps and guitars. Then behind them was the second car. Like a convoy.

‘So, we’re going down the road and there’s this car coming towards us, in the middle of the road. There’s a ditch on the side of the road, so we couldn’t go off the road. Angelo just managed to scrape past it. Then in the rear-view mirror I just saw this ball of flame, like a bomb had gone off. The car had gone straight at the truck and the truck had driven over the top of the car and exploded.’

‘Then the car come into us. It came in so hard it threw us up in the air. We flew up and our petrol tanks blew up. We went up in a mushroom, like explosives, like a bomb.’

Edward Claude Love [Woody] was driving the truck with John Parker [Car John] and Les Graham [guitarist] next to him in the cabin. ‘Woody was saying to me the guy wouldn’t turn his lights down,’ Graham recalls. ‘I just knew straightaway, he’s asleep or he’s … I didn’t think about him being pissed, I really thought he was asleep. Driving over the Nullarbor is so far, it’s so easy [to fall asleep at the wheel]. I reached over and pulled Woody towards me. Car John was in the middle. It was instinct, just natural instinct. We were all hugging together like a big ball, so we were too big to go through the front window. Otherwise we would have been splattered out through the front window from the impact.

‘Then the car come into us. It came in so hard it threw us up in the air. We flew up and our petrol tanks blew up. We went up in a mushroom, like explosives, like a bomb. This is amazing; it didn’t put the truck on the side, it put us on the roof. It actually flipped us right over on the roof. Then it slid down the road while we were still in the cabin. There was the most endless screeching noise. I can never forget it. It was just continuous, this noise. The back of the truck was scraping on the bitumen. I know it was a matter of seconds but it was just forever, that noise. I was waiting for it to stop but it wouldn’t. It all happened in slow motion. Even the sound.

‘The truck was in flames while we were still inside it. When it stopped we got out through the front window. The windscreen was gone. When we got out there were flames everywhere. That car went completely underneath us. It pulled the front end out of the truck. The two front wheels were on the side of the road. It came out from underneath the back of the truck and we had a car behind us and they had to do a lot of swerving to miss it.’

The driver of the car died in the vehicle and his two passengers were hospitalised for weeks. Woody, Car John and Les Graham sustained minor injuries and were held overnight in hospital for observation but were not detained.

‘The truck exploded in Norseman,’ says Mick Pacholli. ‘I didn’t know where any of the band was. Les rings me, I say, “Where is everyone?” “I don’t know.” “Well, you better find them because we’ve got a gig in three days, mate.” I said, “Is anyone [in the band or crew] dead?” They’ve gone, “Nope.” “Well, we’re doing the fucking gig,” I said. “I’ve already been down to Troy Music. I’ve got brand new guitars coming up boys, Bart’s got a new drum kit. Just make sure the band’s there.” And he did.’

It was hard enough being a rock band on the road in Australia in the 1980s. Being a black band just added another degree of difficulty. A lot of the time, No Fixed Address really must have felt they were on the wrong side of the road. But not only did they survive; they persevered. And they endured.