In November 1975, London was finally ready for Bruce Springsteen

Lately, I’ve been thinking about Bruce.

First, I saw the film, Deliver Me From Nowhere. Excellent. Shortly afterwards, I read Bruce, the authorised biography by Peter Ames Carlin. Pretty good. Then I realised it was coming up to fifty years since I travelled from Bath to London to see the man. I got to reminiscing. Dug out some old letters and clippings. Hit the internet. And came up with this – the story of how I came to be at the Hammersmith Odeon on 24 November 1975, with a bunch of American college students.

Four months earlier, in July 1975, I was standing beside the road on the outskirts of Monmouth in South Wales. My red rucksack was by my side and my left thumb was out. As sometimes happens when you cast your fate to the wind, a car stopped, and life took a left turn.

I was 21. I had a science degree in my pocket, and a year as a public servant in Canberra under my belt, but felt I’d reached a dead end in Australia. I still considered myself Scottish so, nine years after my family had emigrated, in April 1975 I arrived back Britain on a one-way ticket to see for myself what we’d left behind.

After doing the rounds of the aunties and uncles in Scotland, and a stint as a youth hostel warden in Edinburgh, I hit the road. I had a ticket to the Cambridge Folk Festival at the end of July and was meandering through Wales, heading in the general direction of Glastonbury. My interest in the Somerset town had been piqued in Edinburgh by the mix of Holy Grail and Arthurian myth and legend described in John Cowper Powys’ magnum opus A Glastonbury Romance.

Chris and Wendy were in the car that stopped. When I said I was going to Glastonbury, they said, we live in Bath, there’s a really happening alternative scene there, why don’t you come with us and check it out? Why not? I thought.

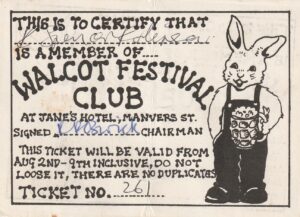

We arrived in the city in the midst of preparations for the annual Walcot Festival. Organised by the Bath Arts Workshop, the festival promised ‘an eclectic and cheeky mix of music, theatre, alternative technology and community events’.

Through Chris and Wendy I met Richard and Geri from the alternative technology group Comtek, and some of the other organisers. The vibe was friendly and welcoming, and I offered Mac and Polly a helping hand to prepare the festival club in the basement at Jane’s Hotel in Manvers Street. Then I headed off to Cambridge, vowing to return in the first week of August for the festival itself.

Len and Becky from Auntie Margaret’s Teashop on the Paragon did the food for the festival club, and again I offered to help out. We got on, and after the festival I followed them back to Auntie Margaret’s, working as a kitchen hand and waiting on tables. Accommodation in the city was scarce, but many fine Georgian terraces were vacant and squatting was popular. Through contacts in the alternative network, I managed to secure a room for myself and my red rucksack at 12 Belmont on Lansdown Hill.

Peter Bradshaw, who managed Jane’s Hotel, had swung a deal to house and feed 32 US students from Union College, Schenectady, NY who were coming for a term at Bath University on a student exchange program. He needed kitchen staff to feed and serve them. After the success of the festival club, Len and Becky were the obvious choice. And having proved myself useful, I persuaded Becky to bring me along for the ride. The basement was converted into a hangout space for the students, with a stereo and sofas, and I quickly made friends among the young Americans. There was even a hint of romance in the air.

A month later, in a letter to my family back in Australia, I wrote, ‘Most of my time is spent at Jane’s – it’s really nice there. Everyone is friends with everyone else, there is no bosses/workers division – no-one will tell you what to do unless you ask – it’s very loose and relaxed and I enjoy it.’

In an echo of a track from Bob Dylan’s recently released Blood on the Tracks; there was definitely ‘music in the cafes at night’. This included multi-part harmonising on the Grateful Dead’s ‘Uncle John’s Band’ and ‘Trucking’ around the upstairs piano; and a basement soundtrack where Jefferson Starship’s Red Octopus; Jackson Browne’s Late for the Sky’; Dave Mason’s Alone Together; Roxy Music’s Siren and Dylan’s latest all got solid spins. Not to forget Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J., the debut album from an unfamiliar American performer.

My core posse in the student cohort comprised Howie, Amy, Jay, Dana, Bill and Werbs. We bonded around the music, the dartboard at the local pub, and the beatific influence of the crumbly light brown Moroccan hash that was in such plentiful supply in Bath’s alternative scene.

I slipped into the role of tour guide, taking Howie, Amy and Jay on a trip to Little Solsbury Hill, site of an ancient hill fort just outside Bath (yes, the one Peter Gabriel later wrote a song about). Joined by Bill and Dana, the four of us also embarked on an incident-packed six-day Scottish holiday in a borrowed Kombi van. We made it to Edinburgh and Oban, but two flat tyres, a flat battery and a case of food poisoning (er, yes, it was me) put a slight dampener on the road trip.

Into this convivial atmosphere, the release of Springsteen’s Born to Run was a definite event. It was fresh, bold, exciting and powerful. For weeks, the basement throbbed to the strains of ‘Thunder Road’, ‘Backstreets’ and ‘Jungleland’, and all the while Howie waxed lyrical about the live shows by the Boss he had seen back in the States.

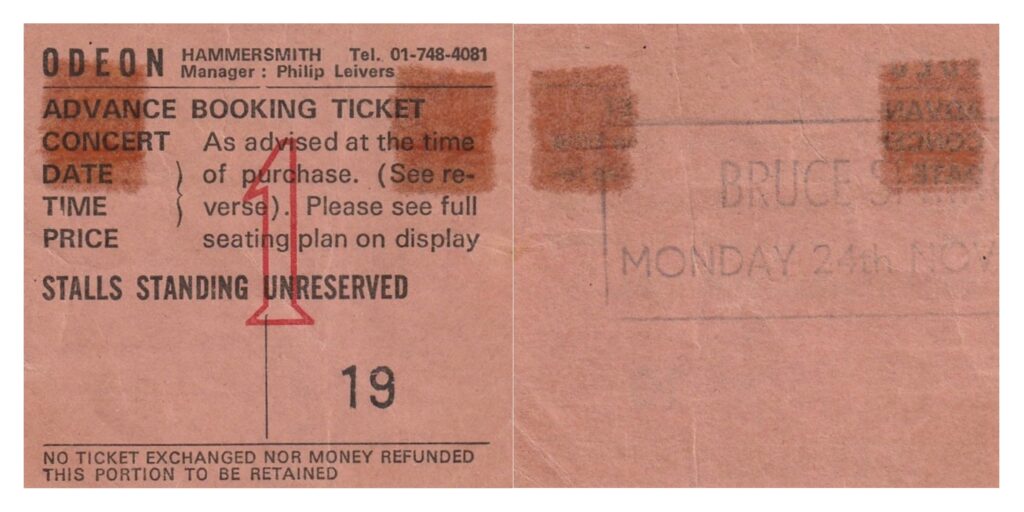

When it was announced Springsteen would be making his international debut in London in November, plans to attend were immediately hatched. The first show on 18 November sold out, but a second, on Monday 24 November was quickly added, and tickets – ‘Stalls Standing Unreserved’ – were secured. Four or five of us went: definitely Howie and Jay; probably Dana and Bill; and possibly Werbs as well.

Logistics were not overly complicated. The train from Bath Spa to Paddington took between an hour and a half and two hours. The tube from Paddington to Hammersmith about 15 minutes. And then a six minute walk to the Odeon.

For some reason, the band didn’t come on stage until 9 pm. With the last train back to Bath leaving Paddington at 11.30, if the Boss played one of his legendary long shows, we would have to bail before the end. And so it proved.

After fifty years, my memories of the evening are somewhat hazy. I do recall we were in a standing area, behind the stalls downstairs, and Springsteen wore a dark brown floppy woollen hat. Images from the night show him in a black t-shirt and loose cargo pants, while Clarence Clemons was resplendent in a white suit and black fedora hat with a white band.

As for the actual performance? Hmm … (long pause) … er, nope. I recall it was exciting and I enjoyed it, but I made no notes. Many years afterwards, Springsteen himself said it was a bit of a blur.

Fortunately, in these days of advanced rock archaeology, not only is there a setlist but also a super high quality recording, available to purchase from nugs.net .

In May 1974, influential music critic Jon Landau had seen Springsteen perform in Boston and wrote, ‘I saw my rock and roll past flash before my eyes. I saw something else: I saw rock and roll’s future and its name is Bruce Springsteen.’ However, the New Jersey rocker’s first two albums had failed to make much of an impact, and Columbia Records considered Born to Run his last chance to deliver on the promise.

The reaction to the album in the US was overwhelmingly positive. So much so, things got a little silly. On 27 October 1975, Springsteen was on the cover of both Time and Newsweek, an unprecedented event for an up-and-coming performer. The needle on the record company publicity machine was way up in the red (overkill) zone. Trade press ads in the US proclaimed: ‘Finally. The world is ready for Bruce Springsteen.’ That may have played well in Peoria, but when the taste-makers of the UK rock press attending Springsteen’s first London show at the Hammersmith Odeon were confronted with a marquee blaring ‘Finally. London is ready for Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band’, the hype was a little harder to digest.

After the event, the conventional narrative was that Bruce was nervous, the audience reaction was muted (which rarely happened Stateside) and this threw Bruce off his stride. In Bruce, Peter Ames Carlin wrote, ‘The memory of the show travelled across the next three decades as a story about a disaster; the collision of a rattled artist with an aggressively unimpressed audience.’

The release of the 18 November 1975 concert on DVD (in 2005) and CD (2006) gave the lie to the prevailing wisdom. In the liner notes to the DVD, Springsteen himself wrote: ‘For me, the set went by like a freight train. Later, all I remember is an awkward record company party, that “what just happened?” feeling, and thinking we hadn’t played that well. I was wrong. With the keys to the kingdom in front of us and the knife at our throat, we’d gone for broke.’

In his review of the concert in the Times the following day, Beatles’ biographer, Philip Norman was certainly impressed. He wrote:

‘Having seen Springsteen at Hammersmith, and attempting now to weigh my words, I can say only that he is wonderful. He is as devastating a talent as popular music has ever produced; more so for having been produced practically by accident.

‘His records, good as they are, leave one unprepared for the strength of his stage performance. He is discovered alone in the spotlight, a small unkempt figure in baggy trousers, a woollen hat. No studio has yet captured the resonance of his voice.

‘Of all analogies, the one with Bob Dylan is most appropriate, and most misleading.

‘There is the same originality, uncontrollable, raging, uttered in its own unmistakable voice. But Dylan was a convert where Springsteen was born. He is a child of rock’n’roll, and of all its cliches; the motor cycles, the funfairs, the drag racers. He sees them with both illusion and disillusion, with punk love and weary insight.

‘In rock’s terrible conformity, there is the further excitement to be felt at the birth of an entirely new character. Insubstantial, strangely innocent with his shirt hanging out, he is somehow even excluded from the smartly dressed members of the E Street Band. Perhaps we see rock’s first Charlie Chaplin. Whatever we see, it does represent extraordinary hope.’

Watching the video of the 18 November show fifty years on, I would also rate it an impressive performance. But on the evidence of the audio recording now also available, what happened six nights later, on the night I attended, was next level.

Michael Watts’ review of that 24 November concert, titled ‘Springsteen delivers the goods’ (Melody Maker, 29 November) was effusive. ‘Springsteen played three-quarters of an hour over time, returned to the stage five times, and did ten encores in all, mainly of Chuck Berry and Mitch Ryder material, but including such unlikely numbers as “Twist and Shout” (Beatles version), Elvis’ “Wear My Ring Around Your Neck” and Jackie de Shannon’s “When You Walk in the Room”. It was a night on which one’s emotions were completely exhausted.

‘The truth is, rock music needs Bruce Springsteen. His is a large personality in an era of small talents. He believes in the power of songs and communication at a time when rock music, particularly that of English groups, has made a virtue out of technique alone.’

Erik Flannigan’s review of the recording is equally glowing:

‘The London ’75 narrative was a two-parter, the other half being that the response to the first London show motivated an extraordinary second performance by Springsteen and the band at Hammersmith Odeon six days later, on November 24. Whether or not there is a causal relationship between the reception to the first gig and the resulting second show, the myth is right about one thing: London 11/24/75 is brilliant.

‘After performing 16 songs at Hammersmith 1, Bruce and the band unleash 22 killer cuts at Hammersmith 2, making eight overall changes to the set, a whopping seven of which are cover versions. The mindset seems to be, bust out the full arsenal and hit ’em with everything we got. Boy do they ever, giving a musical history lesson in the process and performing some of the best live versions of material from Springsteen’s first three albums, shifting effortlessly between full tilt and slow, nuanced majesty.’

Through the wonder of modern technology (MP3 digital files via the internet) fifty years down the line I was able to revisit the concert. Here is my take.

The performance opens with the first two tracks from Born to Run. Roy Bittan provides a gentle piano intro to ‘Thunder Road’ and is joined by Springsteen on harmonica. That’s it; Springsteen sings the song to a stripped back arrangement, with the lyrics front and centre. The audience is appreciative. The rest of the band come out and ‘Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out’ again starts with the piano, then Miami Steve van Zandt’s guitar and Clarence Clemons saxophone join in, and the band locks into a groove.

Some of Springsteen’s cast of characters – Crazy Janey and her Mission Man, along with Wild Billy and his G-Man, Hazy Davy and Killer Joe – dart in and out of ‘Spirit in the Night’, before a stark, dramatic reworked version of ‘Lost in the Flood’ provides the first real highlight of the night. A crisp ‘She’s the One’ follows, and then Bruce and the band nail a version of ‘Born to Run’, a traveller’s anthem fresh out of the blocks.

At this point in the first Hammersmith show, Springsteen and the band slipped into an overlong and musically self-indulgent ‘Kitty’s Back’. This night instead, in the first nod to one of his musical foundations, Springsteen plays a long version of ‘Pretty Flamingo’, a 1966 hit by British R&B/pop outfit Manfred Mann. Bruce actually speaks to the audience as well (he didn’t speak at all on the 18th), relating a story of how he and a friend used to sit out on the porch of his home on South Street and watch ‘this one girl’ walk by.

Full throttle versions of ‘Growing Up’ and ‘It’s Hard to Be a Saint in the City’, follow, then a heartfelt ‘Backstreets’, before a second Manfred Mann cover, ‘Sha La La’, a crisp version that motors along and features some juiced-up sax from the Big Man.

Two extended pieces bring the first part of the show to a conclusion. A majestic rendition of the street epic ‘Jungleland’, with an extended sax solo, captures the full scope of the recorded version, then a rollicking version of Rosalita’, with the band tight and swinging as they gallop to the finish.

In her review of the night, Robin Katz wrote: ‘At 11 pm schizophrenia set in. While doing ‘Rosalita’, his last number, Springsteen and his band became three dimensional, rocketing into the energetic powerhouse everyone had read about. Springsteen was all over the stage, all over the runways, on top of the organ and halfway on the piano, machine gunning the audience and the audience machine gunned right back.’ (‘A spirit in the night’, Sounds, 4 December 1975)

If Katz is correct about the time, and given we needed to get to Paddington to catch the last train home to Bath, myself and my American compadres probably bailed at this point. On the way out, I souvenired a concert poster from the foyer (see main image above).

For a description of the encores we missed, I doubt I can do better than Erik Flannigan. Take it away, son.

‘We move to a jaw-dropping encore that opens with an evocative version of “Sandy,” resplendent with Danny’s accordion and the Big Man’s baritone sax. Bruce paints a picture with his words, singing every line with vivid conviction. This is as good as “Sandy” gets.

‘From there, it’s time for an E Street Jukebox session that is the stuff that built the legend. The tour debut of “Wear My Ring Around Your Neck” gets us started, with Bruce turning up the juice on the Elvis Presley tune. …

‘Next, we’re on to the “Detroit Medley” and a special disco dance lesson, as Bruce teaches Londoners the “New Jersey Hustle.” That wraps the first encore. The band leaves the stage and Bruce returns for a solo piano performance of “For You.”

‘Holy shit.

‘Over the course of nearly nine rhapsodic minutes, Springsteen reinterprets “For You” to wonderous effect. Everything changes, from vocal intonation to phrasing to tempo. … The clarity of the recording is remarkable.

‘It isn’t just his singing, either, as he thrillingly speeds up the piano behind lines like, “Your strength was devastating in the face of all these odds,” and later when he concedes, “So you left to find a better reason than the one you were living for.” …

‘“When You Walk in the Room” brings pure elation, the Searchers’ cover soaring and showing the UK group’s influence on the E Street sound, which can be heard all the way up through The River sessions.

‘The encore continues with “Quarter to Three,” … Springsteen has Hammersmith eating out of the palm of his hand. The show could have easily ended with the Gary U.S. Bonds classic, as many Springsteen shows have before and since, but no. Turns out there’s gonna be an after-party, and Bruce and the band are gonna pull out ALL the stops.

‘Bruce says he learned to play “Twist and Shout” “out of a Beatle book,” and he uses it to work up the crowd even further as he stops mid-song on “doctor’s orders,” only to be revived by his bandmates.

‘Two minutes of sustained applause compels a third encore, and pushing the C1 button brings up Chuck Berry’s “Carol” in its final 1975 appearance. Stevie Van Zandt seizes the occasion for more guitar heroics. That sonic depth noted above can be especially felt when Bruce calls for Clarence’s “big notes” on baritone sax. …

‘The epic Hammersmith performance seems to be over, but Springsteen can’t quite walk away, calling out the key of A and breaking into a spontaneous version of another Berry classic, “Little Queenie.” Collectors know the song’s famous premiere at the Milwaukee “bomb scare” show in October 1975; this one shares that same ragged-but-right spirit, along with an unmistakable sense that on this climatic night in London, the end of Bruce’s first-ever visit to Europe, he simply didn’t want it to end.’

Phew.

* * *

Back in Bath, the last reels of the Jane’s Hotel episode spun out that week.

Two days after Springsteen, there was a Thanksgiving dinner for the students at the hotel, followed by a party at the local pub, The Ram at Widcombe. The next day, they were gone.

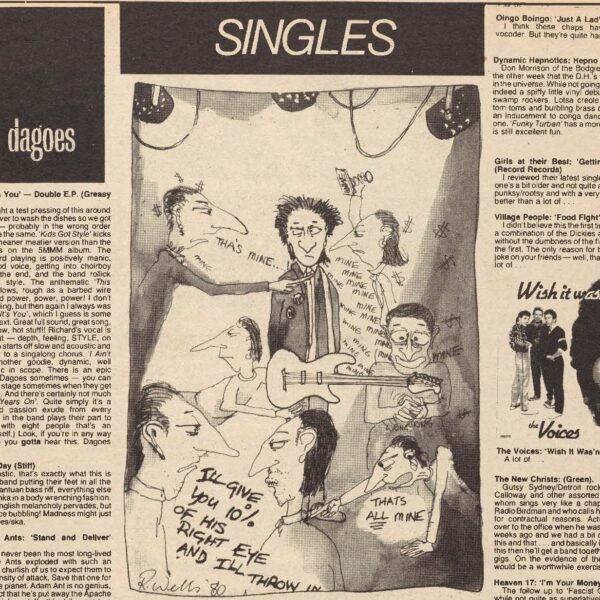

However, I’d found my tribe, and moved into a bedsit on Lower Bristol Road in Twerton. Then, when Mac and Polly decamped to the country, I took over their flat in Rivers Street, and stayed in Bath another two years. All the while, the music was going round my head. I used to devour the weekly rock press; NME, Melody Maker and Sounds. Bristol was only 10 miles away and most of the major concert tours included Colston Hall on the agenda. Southside Johnny and the Asbury Jukes with Graham Parker and the Rumour was a standout; but also Dr Feelgood, AC/DC, and T. Rex with The Damned. I saw The Who, with Little Feat and the Sensational Alex Harvey Band in Swansea; Eric Clapton and Freddie King at Crystal Palace; and the Boys of the Lough and David Bromberg at the 1977 Cambridge Folk Festival. And punk happened, which was very exciting.

While in Bath, I took my first tentative steps as a ‘Rock Journalist’, with an interview with Tim Finn of Split Enz, and live reviews of the Sex Pistols in Newport, South Wales and the first Stiff Live Stiffs tour (featuring Elvis Costello, Ian Dury, Wreckless Eric, Nick Lowe and Larry Wallis) at Bath University.

Then, having had a close look and coming to the same conclusion as Mr Johnny Rotten that there was ‘no future in England’s dreaming’, my folks sent me the fare and I came home. To the land down under.

Because it was during that two and half years back in the U.K. that, while not feeling any less Scottish, for the first time I also felt Australian.

After I had returned to Australia, Peter Bradshaw wrote me a letter. ‘Obviously – thinking of you I have the memory of Becky … + American students – those days are still vivid memories. Bath has the power of leaving mental pix for many of us … In my heart – people are places and places of significance are people.’

So, so true.