The Drums, by Rob Hirst

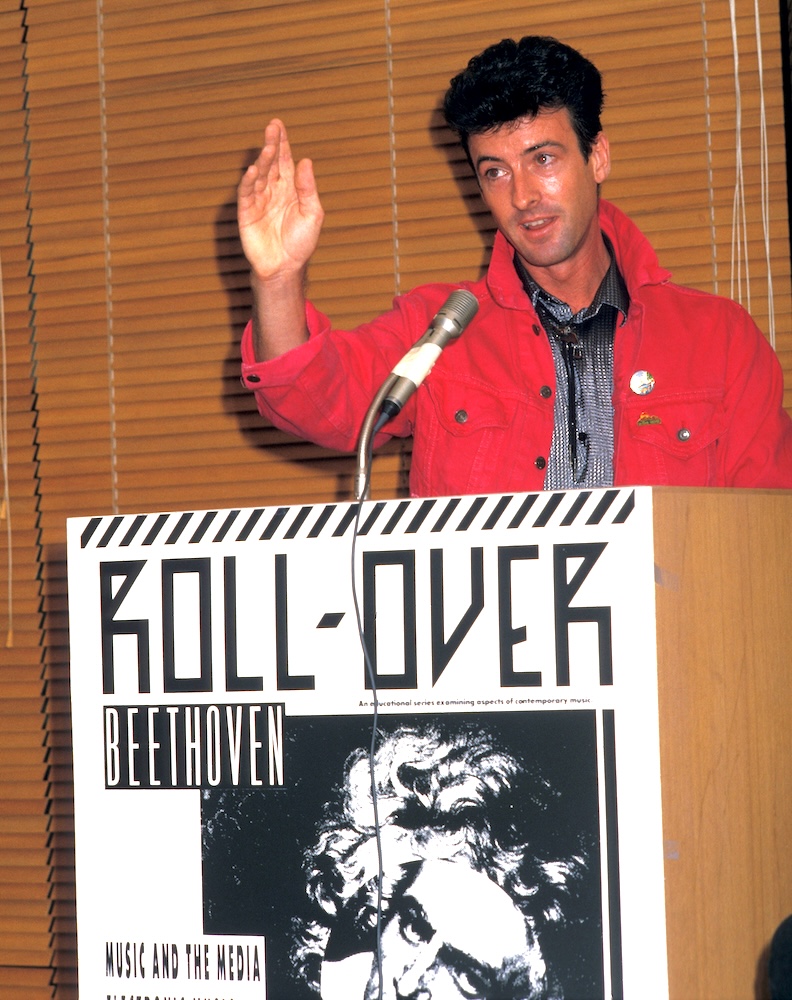

I was delighted when Rob Hirst accepted my invitation to contribute a chapter on drums to Roll Over Beethoven.

As editor of Roadrunner and Countdown magazine in the late 70s and early 80s, I’d covered and written about the steady and uncompromising rise of Midnight Oil to the top rank of the Australian music industry. Describing a March 1981 open-air concert at Adelaide University I wrote: ‘It was awesome, brilliant, the closest to a perfect rock gig I’ve ever seen.’ Someone at the Oils obviously liked it and put it on a promo postcard.

In 1987, I was editing Roll Over Beethoven, a magazine series designed to provide content for new rock electives in the NSW music syllabus. Thinking about someone to write about drums, Rob was first in line. I knew he was a smart dude, but I didn’t expect such an erudite exposition of the development of the modern drum kit, and such a perceptive account of the greats in the field. But should I have been so surprised? If ever there was a renaissance man in Australian rock, Rob was it. Creative, thoughtful, professional, passionate, political, and ever humble. One out of the box. RIP Rob Hirst, 1955-2026.

* * *

You’re winding up at the end of another long show. Your right foot aches on the foot pedal and your left leg feels like it has been severed at the knee-cap. Both your wrists have cramped up at ninety degrees and rusted there, from the salt ‘n’ Staminade sea cascading from your pores. Your eyes, blinded by supertroopers, look like two over-ripe bloodplums ready to burst. Your eardrums have shredded like jockettes in a twin-tub washing machine. Your lungs, full of the gaseous residue of che lighting man’s hyperactive smoke machine, feel like a ‘Quit-for-Life’ advertisement. You’ve been yelled at by the singer, aurally assaulted by the monitors and the guitarist has decided that HE wants to play the drum solo too. In a fit of pain and frustration, you finish the last song and kick the tom-toms VFL Grand final-style into the audience, drumsticks flying like debris from a Tasmanian woodchip mill. Encores now being out of the question, you dry off, get changed, relax before the golden hordes teem backstage. You spend twenty minutes talking gibberish to one of the ‘fans’ and then the bomb is dropped: ‘So what do youse do in the group, then?’

‘I’m the drummer …’

Why would anyone want to play drums? What common bond of insanity compels the world’s professional skinbeaters? A primitive urge? A great way to drive your folks to drink? Roger Hawkins of the Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section claims: ‘I played all the time because I was real fat, ugly and none of the girls liked me … I was about twelve or thirteen …’

Ex-Beatle, Ringo Starr says he became a drummer because he missed by two months being called up into the Army! Whatever the reason, the drumming of fingers on table tops and the thump-thump of feet on the ground are the trademarks of drummers around the world, and rhythm is one of the basic elements of music itself. From the ‘talking’ drums of the tribes of Africa to the marching drums of Asia; from the percussion instruments of the original Australians, the Aborigines, to the orchestral drums of the great civilisations of Europe.

So how did the modern rock drum kit come about? To discover this, you have to take a musical journey backwards for about a hundred and fifty years through the styles that eventually gave us rock ‘n’ roll in the mid-1950s. Back through rhythm and blues, country and western swing, blues, jazz, ragtime, gospel and minstrel music to the songs of the Negroes transported from Africa to work as slaves in the cotton and tobacco plantations of the American South. Before the Civil War of the early 1960s minstrel bands and church gospel groups used tambourines, triangles and bone clappers to accompany their ‘call and response’ chants and hollers. But it wasn’t till Scott Joplin made ragtime (listen to ‘Maple Leaf Rag’) a national obsession at the turn of the century that the ‘drum kit’ appeared. It comprised a huge marching style bass drum and a side drum, using skins from calves, goats, pigs or anything else that wandered past at an inopportune moment. At the same time, the drummer got a sit down job, since the heavily syncopated 2/4 time of rag time (‘ragged time’) – a combination of minstrel banjo music, plantation songs and European dances like the waltz and the polka – required the two drums to be hit very quickly, very often.

By the time the Original Dixieland ‘Jass’ Band had made the first recordings of what truly can be said to be a JAZZ band (‘Darktown Strutters Ball’, ‘Indiana’) in 1917, various ‘traps’ had been added to the nascent drum kit. A small cymbal now hovered awkwardly above the bass drum alongside cowbells, woodblocks, and other assorted junk, and the wire ‘snares’ used for parade drums were added to the side drum (any off-cuts could be used to make wire brushes, for a ‘sweeping’ sound on the ‘snared’ drum).

Hot drummers of the time were Baby Dodds and Zutty Singleton, both from New Orleans and of Louis Armstrong/King Oliver fame. The recordings of this early jazz age sound dreadful today, but the spirit of the musicians is undeniable and the jerky 2/4 drum patterns and ‘press’ rolls are clearly felt if not always heard.

The idea of the drummer as a band leader was born in the 1920s in the form of Chick Webb, whose driving 4/4 bass drum/ride cymbal style was a major influence on Buddy Rich and Gene Krupa in the decade to follow. Webb’s ‘Harlem Stompers’ played a louder, brasher style of jazz which, during the 1930s was a big hit with urban blacks who had been forced to travel northward to New York and Chicago in the Great Depression in the search for work. Big Sid Catlett, Jo Jones and Davey Tough were some other famous drummers of the ’30s and ’40s. Catlett played with Louis Armstrong, Fletcher Henderson and Benny Goodman, and his immense power drove these big bands at full throttle.

The extroverted Catlett, in his sharp green-check suits, was also the first in a long line of showman drummers. Gene Krupa’s showmanship has made him one of the best known drummers of the century. During his Benny Goodman Orchestra period ( 1934-8), with Tommy Dorsey ( 1943-4) and leading his own bands, Krupa made drums a household word, and influenced a whole generation of ’60’s rock drummers including The Who’s Keith Moon.

The concept of the ‘drum battle’ also emerged at this time as Krupa was pitched against the likes of Buddy Rich in alternate soloing jousts. Rich was fast, accurate and probably the greatest big band drummer of all time with a reputation as fierce as his style. He died early in 1987 at the age of seventy after a lifetime of practising up to eight hours a day. Rich’s drum set and the one Krupa used had grown now to include two tunable tom-toms, a ‘sock’ (hi-hat) cymbal played with the left foot, a large ‘ride’ cymbal which carried the swing pulse, and crash cymbals or accents. Louis Bellson initiated the use of twin bass drums, and drummer/vibraphonist Lionel Hampton began turning his drumsticks around and using the thick end for more power. The ‘traps’ of the trad-jazz days had largely disappeared, bass drums had become smaller, soft mallets were sometimes used instead of sticks and brushes, cymbals often had ‘rivets’ in them for a ‘swish’ sound, and the great drums made by Ludwig, Gretsch, Slingerland and Premier were lovingly wrapped in ‘mother-of-pearl’ finishes with names like ‘Champagne Sparkle’. Drum kits were recorded by single microphones used to pick up an entire orchestra, so always have a ‘live’ sound on the records of this swing era. Meanwhile, the drummer/bandleader tradition was upheld by virtuoso Max Roach, one of the ‘Bebop’ pioneers who extended the idea of polyrhythms as heralded by Kenny Clarke. The political significance of his later work can be heard on the We Insist! Freedom Now Suite, a cry for racial equality. Art Blakey’s large drum ensembles pushed drums further as frontline instruments, the African drumming tradition loud and clear in his music.

Then along came Rock ‘n’ Roll; drummers borrowed heavily from all the styles available by the mid ’50s. D .J. Fontana grew up listening to the big swing bands of the 40s but used a heavier backbeat for the Elvis Presley classics ‘Hound Dog’, ‘Heartbreak Hotel’ and ‘Jailhouse Rock’. Presley wanted such a big sound that, in 1960, he added another drummer for live shows, making Fontana and Buddy Harmon the first double-drumming team in rock. Buddy Holly and the Crickets’ drummer Jerry Allison was influenced by country and western and rockabilly bands, but also by what was referred to as the ‘root blues’ – blues performed by such figures as Lightnin’ Hopkins, Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf. (The existence of racial segregation in the South did not mean that blacks and whites were ignorant of each other’s forms – interested white New Yorkers had travelled to Harlem’s Cotton Club in the ’20s to hear black music played). These ‘R’n’B’ artists, plus the heavy 4/4 backbeat of the Little Richard and Chuck Berry hits, influenced an entire generation of English groups like The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, The Who and Cream, who literally ‘sold’ R’n’B back to American youth in the 1960s.

The Stones’ drummer Charlie Watts has said ‘I always wanted to be a black New Yorker’, and like Ginger Baker from Cream had a jazz background playing with Alexis Korner’s Blues Inc. Beatle Ringo Starr also came from the ‘R’n’B’ band Rory Storm and the Hurricanes before replacing Pete Best in the Beatles. Ringo’s ‘matched-grip’ style (holding both sticks with wrists on top) and straight-ahead time keeping influenced drummers around the world, but particularly the ‘Merseybeat’ groups from the Liverpool area of England.

If Ringo played straight and sat tall on his ‘mini-kit’, Keith Moon of The Who played wild and surrounded himself with more drums than most players hit in a lifetime. Moon loved Krupa’s flair and the ‘surf’ drumming of ’60’s southern Californian groups like Jan and Dean and single-handedly (double-handedly?) redefined rock drumming’s outer limit. Moon attacked his drums with a vengeance, sometimes smashing the whole lot up for good measure. As Charlie Watts said, ‘Keith Moon is what legends are made of’, while Moon used to call himself the ‘best Keith Moon-style drummer I know’.

But while Moon was making his drums sing, Levon Helm of The Band was making them cry; Helm’s understated drumming and singing can be heard in the Civil War Anthem, ‘The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down’. And in Australia, Snowy Fleet of the Easybeats and Stewie Spears of Max Merritt and the Meteors were making names for themselves at a time when most Aussie groups were carbon copies of the latest English fad.

Other drummers were happiest out of the ‘band’ context altogether, or preferred to shun the limelight in favour of studio work. ‘Session’ drummer Hal Blaine played on Phil Spector’s big production hits (e.g. ‘He’s A Rebel’ by the Crystals), ‘Mr Tambourine Man’ by the Byrds and the Mamas and the Papas’ ‘California Dreaming’, as well as countless other sessions. He also ‘ghost’ drummed for Dennis Wilson on the early Beach Boys hits like ‘Surfin’ USA’ and ‘I Get Around’. Bernard ‘Pretty’ Purdie says he ghosted for Ringo on 21 of the early Beatles hits, and will disclose which ones when someone offers him enough money!

By the time the seventies rolled around drums were in trouble; wooden drums were being replaced by Perspex, metal or fibre glass hybrids; warm sounding ‘skins’ had been superseded by harder sounding plastic ‘heads’; nylon tipped drumsticks had arrived and some bass drums and tom-toms had their front ‘heads’ removed entirely with a microphone stuck inside each one. To add insult to injury, drums were then taped down and recorded in padded boxes to ‘dampen’ their volume and eliminate overtones. Enormous drum kits with rows of concert toms, timbales, rototoms, octobans and a thousand cymbals became the standard – some players now looking like puppets in a drum shop.

The best 70s’ drummers avoided all these pitfalls, with John Bonham of Led Zeppelin and Deep Purple’s Ian Paice leading the hard rockers, Bill Bruford (Yes, King Crimson and Pavlov’s Dog) and Carl Palmer (ELP), using brains and technique respectively in the ‘classical’ rock genre, and Billy Cobham commanding the jazz/rock school, playing ferocious drums in John McLaughlin’s Mahavishnu Orchestra. In Australia, Gary Young of Daddy Cool harked back to rock’s R’n’B roots while Mark Kennedy (Ayers Rock), Freddy Strauks (Skyhooks) and Alan Sandow (Sherbet) added immeasurably to those bands’ successes.

But if drums were in trouble in the 70s, so was the audience; Ginger Baker had set the pace with his epic drum solo (aptly named ‘Toad’) on Cream’s Wheels of Fire album, Led Zeppelin’s Bonham made people sit through a 40 minute plus live solo, in which he played four sticks at once and then with no sticks at all to keep the interest up. Worst of all was the ‘ln-A-Gadda-Da-Vida’ drum solo courtesy of Iron Butterfly, which everyone knew and everyone hated. The best solos, of course, were the simple drum breaks, like Charlie Watts’ introduction to ‘Honky Tonk Woman’, with producer Jimmy Miller playing the cowbell.

The late 70s and 80s have seen drums in grave danger of disappearing altogether. The strict dance timing of disco music was the perfect vehicle for drum machines, rhythm generators and sequencers to gain popularity. Drummers now often record in perfect sequence with a ‘click’ track to achieve perfect time, or are dispensed with completely (Horror!). Ralf Hutter and Florian Schneider of Kraftwerk, with their 1977 classic Trans-Europe Express had shown the ‘relaxed’ feel of machine music. Names like Linn (sequencers), Simmons (electronic drum ‘pads’), Fairlight (multi-purpose, Australian-designed music computers), Emulators and Akai samplers are replacing and complementing the old drum brand names, with some spectacular results. Producers are now likely to be frustrated drummers playing with rhythm generators as well as their traditional roles. (Get the Art of Noise’s In Visible Silence for an example of producers gone mad in the studio). Drummers have fought back, of course, with Stewart Copeland of the Police combining another ‘roots music’ source (reggae) to his jazz and rock background, and Phil Collins rediscovering Phil Spector’s ‘Wall of Sound’ and inventing his own ‘Wall of Drums’.

As a drummer, singer, songwriter, producer and keyboard player the man has just too much talent. (Try to sing and play to ‘In The Air Tonight’ at the same time!)

When all’s said and done, Collins and some of his Australian contemporaries like John Prior, Paul Hester (Crowded House) and Dorland Bray (Do Re Mi) have one great common denominator attitude toward their instrument; ‘HIT them damn things … those drums ain’t gonna bite you … ‘