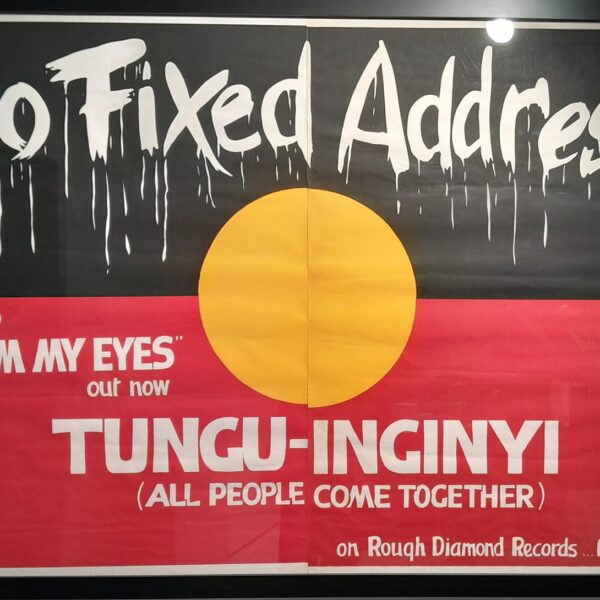

No Fixed Address: young, black and proud

At the time of this Roadrunner cover story from August 1980, I thought No Fixed Address was the most important new band in the country.

A bunch of young Aboriginal musicians at the South Australian Centre for Aboriginal Studies in Music, bouncing around Adelaide from gig to gig, they were about to start filming a movie, Wrong Side of the Road, loosely based on their lives and experiences and songs from their demo tape were getting strong airplay on the new Adelaide community radio station 5MMM. They sounded like nobody else in my experience and they were the first band in a long, long time to send shivers down my spine. I got to know them and as they didn’t have a manager, I tried to help them out. I found them some gigs, took Don Walker from Cold Chisel to see them one night at Hartley College of Advanced Education in Magill—which resulted in a support slot on one of Chisel’s national tours—and when the combination of the magazine and the band got too much, introduced them to Redgum’s manager, Chris Gunn, who took them under his wing. And off they went to (some) fame and (I suspect, not very much) fortune in the Australian music machine of the 1980s.

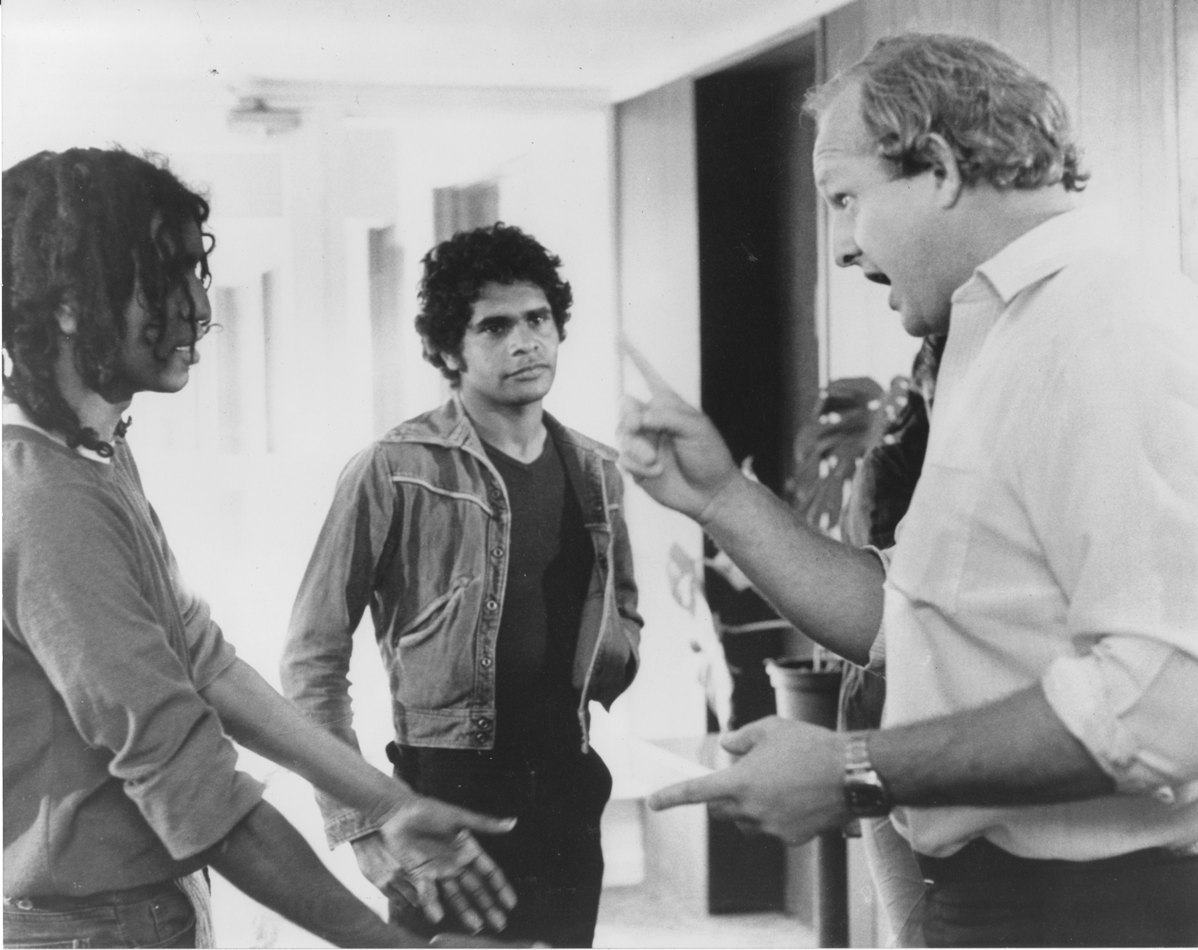

On its release, Wrong Side of the Road won the Jury Prize at the 1981 Australian Film Institute Awards and has recently been fully digitally restored by the National Film and Sound Archive. To coincide with the premiere of the restored film the NFSA’s Indigenous Collections team undertook the ambitious task of bringing the ten surviving Aboriginal cast members back together in Sydney to conduct a series of oral history interviews.

In 2008, We Have Survived was added to the NFSA’s Sounds of Australia collection, the sounds that ‘make up Australia’s history, the sounds that are among the most important to our collective memories as Australians’. Bart Willoughby received a Fellowship in the 2014 Australia Council’s National Indigenous Arts Awards and continues to perform with the Bart Willoughby Band.

∗ ∗ ∗ ∗ ∗

No Fixed Address

Original Aboriginal reggae

On a cold, windy Sunday afternoon about a month ago, I hopped on my bicycle and pedalled the couple of miles to Westbury Street, Hackney, one of the inner eastern suburbs of Adelaide. I was going to interview the members of No Fixed Address, an Adelaide-based Aboriginal reggae band that had been creating quite a stir in Adelaide’s small musical community.

My first impression of the band, confirmed and strengthened by subsequent encounters, was of something possibly unique and undeniably powerful—a black Australian band playing original songs about themselves and their people. And although reggae is not a music native to this country (what form of contemporary music is?), No Fixed Address have taken to it like a duck to water and USED it to get their message across. No Fixed Address look and sound like nobody else in my experience and they are the first band in a long, long time to send shivers down my spine. When they perform We Have Survived (The White Man’s World), the song that ends their set, it’s as if a whole people are speaking out with pride and defiance, qualities that are not often heard from this country’s original inhabitants.

For a whole lot of reasons, political, historical and musical, No Fixed Address is probably the most important new group in this country today. The voice that they speak with has been too often suppressed in the last two hundred years. It’s about time it was heard.

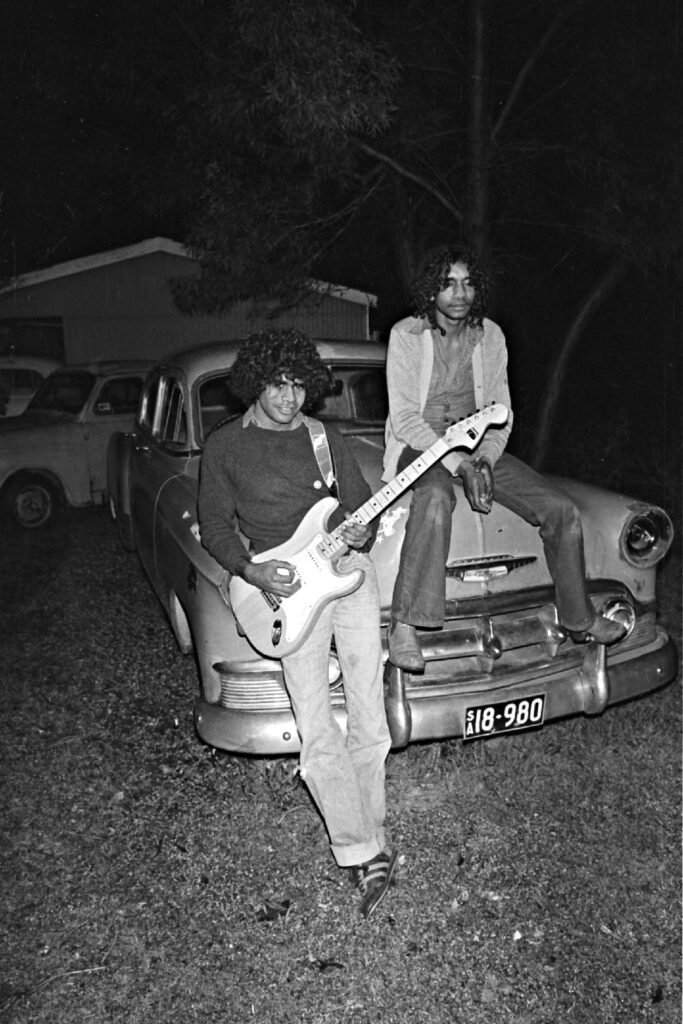

No Fixed Address comprise Bart Willoughby (drums), Ricky Harrison (rhythm guitar), Les Graham (lead guitar), John Miller (more usually known as John John) on bass and Veronica Rankine (saxophone and backing vocals). Bart and Ricky write most of the band’s original material but Les and John John are starting to contribute. Bart and John John are from Ceduna on South Australia’s West Coast, an isolated small town on the edge of the Nullarbor Plain. Les is from Murray Bridge, 50 miles east of Adelaide and Ricky is from Melbourne. The present line-up came together only about ten months ago and virtually went straight out on tour.

Waiting for me at Westbury Street that Sunday afternoon were Les (with whom I’d arranged the interview at a party the previous night), Bart and Ricky. Les was the only one living in the house which is home to four or five other adults and a couple of children (all white). Graham Isaacs, ex-guitarist with Captain Matchbox, and the closest the group have to a manager is one of the other residents. We talk for a while there, have some dinner while watching Countdown, then adjourn to Bart’s house about a mile away to finish talking.

The most outspoken of the three is Bart. Small and skinny with a mass of black curly hair falling over his eyes; he first started to learn drums and guitar at the McNally Training Centre, a ‘correctional’ institution for youth in Adelaide’s eastern suburbs. He picked up a lot of his present technique from a Jamaican drummer called Desmond who played with an early incarnation of Adelaide reggae band Soka. The song From My Eyes is, according to Bart, ‘about the time I was locked up. I was in a big room and couldn’t see nothing … and it’s about getting respect’. That comment about getting respect is one that crops up again and again over the next three hours. Ricky is quiet, soft-spoken but has an infectious laugh and is the reason the band play a couple of Angels covers. Bart and Les call him a punk rocker, but the description hardly fits. He got involved in the band after coming over from Melbourne with Les (‘I was driving around Murray Bridge and woke up in Melbourne…’), and just started ‘boozing talking and playing’.

The present line-up had played only four gigs in Adelaide before setting out on a four-week interstate tour. One of those gigs was at the Port Adelaide Town Hall with two other black bands, Us Mob and Raw Deal, a gig which was broken up by the S.A. Police’s Star Force after it had tried, unsuccessfully, to patrol the inside of the hall.

There was no such trouble on the tour which took No Fixed Address to Melbourne for a week (they’ve just recently been back for a successful two week stint there) then up the North Coast to Bellingen, Coffs Harbour, the Kempsey Aboriginal mission and back down to Sydney. It was a good initiation for the band and no doubt helped the band keep it all together when they got back, considering the lean pickings Adelaide has to offer in the way of gigs and money.

‘The only time we really think and talk about what we’re doing is when we ship out of Adelaide. We stick close when we’re out of town,’ says Bart.

Although the University of Adelaide’s Centre for Aboriginal Studies in Music is still the band’s base (for rehearsing), they say the feeling at the centre is that they’re not really part of it any more. There is strong competition for rehearsal time (there are four other bands there) and obviously if the band are not getting regular gigs, they’re not getting a real chance at the moment to work on their music. As Bart says, ‘It’s easier to write if you’re playing every night and you’ve got your music all around you.’

The recordings that the band have done have been produced by Phil Roberts who once upon a time was producing at Island Studios in London and who has worked with such reggae artists as Keith Hudson as well as numerous African bands. Their last session was paid for by CBS who had expressed interest in the band. However when the resulting tape hit the desk of national A&R manager Peter Dawkins (producer of Dragon and Mi-Sex), he expressed the opinion that it wasn’t ‘slick’ enough. I hope he lives to eat his words.

The big thing for the band at the moment is the making of a film, as yet untitled, which will be coupled with the release of an album. Work on the album will be starting this month. The Australian Film Commission has given Graham Issac and director Ned Lander $40,000 towards the production cost of the film which will be about No Fixed Address and Adelaide black band, Us Mob. Bart describes the plot thus: ‘It starts at the Port Adelaide Town Hall, with all these cops coming in to break up the gig that we’re playing. Then we all pile into these cars and head off to Whyalla. The film talks about the people in the two bands, with like flashbacks. There’s one flashback to me and this big breakout at McNally’s’.

Filming is due to start in September and the tentative release date for both movie and album (which will feature both No Fixed Address and Us Mob) is February (1981). At present the album will come out as an independent. Although there is interest from the major labels, Phil Roberts likes the idea of taking things nice and easy. ‘I wouldn’t like to see the band burn up in six months.’

I ask if No Fixed Address are surprised or find it strange that their music is so obviously enjoyed by a lot of people, particularly white people. Bart replies, ‘Yeah. But it’s a good feeling. I think our biggest feeling when we’re up on stage is seeing mixed people together. Like with half the crowd white and half black getting along together with no trouble. Most of the blackfellows who come to see us feel really proud.’

The last time Bart was in Ceduna was over a year ago. I ask him if he has much connection with tribal people. ‘When you go there.’ he quickly replies, ‘You walk in the daytime and hide under your bed at night, or else they try to initiate you.’ He laughs.

How important is black culture to you, then? ‘Well… just imagine you are a white person surrounded by black people. Yeah? Well that’s how the black is. Surrounded by white people. You can walk down the main street in Sydney and you don’t see one black person. They’ve lost their culture there.

‘We’re trying to be safe. Like if a bunch of West Coasters got together with a bunch of people from Murray Bridge, there’d be a big fight. It’d be big. And there’s all this rivalry between the different missions—it’s like football teams … you know, ‘Next time we’re gonna beat you…’. But we’re doing it for all the black people. Our band’s safe because we’ve got a mixture. But we still get a hard time’.

How much effect on your people would you have if you were a big success? ‘They’re just stirring us up because we haven’t done much yet. Soon as they find out they’ll follow us. We’re not trying to start a revolution. We’re just trying to get what belongs to us’.

‘Yeah… It’s like watching this tree grow… and next minute it’s cut off. And you think, oh the tree should have been there. But it’s not. That’s the way we feel about the land. It’s lost. We’re lost. So what we need to do is to get it so we can find ourselves. We say what’s coming from behind us and also say what we feel too.’

Land rights?

‘Yeah… It’s like watching this tree grow… and next minute it’s cut off. And you think, oh the tree should have been there. But it’s not. That’s the way we feel about the land. It’s lost. We’re lost. So what we need to do is to get it so we can find ourselves. We say what’s coming from behind us and also say what we feel too.

‘We get stirred up by lots of other guys in bands too. Like they say, “We’re rock and roll” and talk really big and say, “We don’t play reggae music ‘cos we’re not religious”. “WE’RE not religious,” Bart says firmly. ‘A lot of people have their own opinions and interpretations on what reggae’s all about,’ interjects Ricky.

‘We’re people from the land,’ continues Bart. ‘And there’s one thing that people have to understand—you can’t control it. It controls you. That’s why they’re building all the houses—so they can control the land. But the land can just (he slaps his fist into his palm—thwack!) … like that, with an earthquake or something like that. That’s the feeling I get with people trying to control the land. It’s really easy when it controls you. The instinct within you … it’s Nature itself, so you just do it and feel a whole lot better.

‘I’m really strong in my land rights. A lot of my songs are about that. We want respect. A lot of people put us down. We’ve never put them down, why should they put us down? Most probably it’s because of what we’ve got, they want.

‘You know why a lot of black people drink a lot, are pisspots and all that? It’s because they’re lost. When you see ’em walking down the street, their heads are down. ..So each time we play they have a good time … and they’re real proud.’

If there is one thing about your song: We Have Survived it’s that it’s a really proud song, I say.

‘When we were playing in Melbourne I just noticed some of the people’s reaction – like “What’s this black dude doing telling us what to do …” some looks like that, you know. But when the song finished most of the crowd really cheered. It was great.’

‘You know why a lot of black people drink a lot, are pisspots and all that? It’s because they’re lost. When you see ’em walking down the street, their heads are down. ..So each time we play they have a good time … and they’re real proud.’

That gig in Melbourne was at La Trobe Uni. supporting Mi-Sex The band also supported Taj Mahal at the Arkaba in Adelaide when the legendary bluesman was touring here a couple of months back. Bart shows me a poster Taj gave him that carries the inscription, ‘To The Best Black Band In Australia’. They’ve already sent him a copy of their new tape.

‘We meet a lot of white Americans’, says Bart. ‘And they say, “Why don’t you go and do it, why don’t you just go and get what you want”. And they just think they’re know-alls. The way the black Americans got to the stage they’re at … you know, respected… is that they did a lot of thinking to outsmart the prejudiced people. That’s what we gotta do. And we will. We’ll outsmart ’em. But just about the only way we can do it is through music where everyone can get together instead of getting pinged off, one by one.’

Ricky: ‘We didn’t even think we’d get this far.’

Bart: ‘We get a lot of stick from people. Like when you get on a bus—you’re sitting by yourself. No-one’ll sit next to you. Only the old people sit there.’

So prejudice is still a real problem for you?

Bart: ‘Yeah, it’s happening every day. Even when we play at gigs—some people walk straight out.’

Ricky: ‘Some people think we’re prejudiced against them. Some people have come up to me and said, “What’s the matter with you. Are you prejudiced against me or something?” ‘

Why would they say that?

Ricky: ‘I don’t know. Maybe because I wasn’t talking to them.’ (Laughs)

Bart: ‘Why should we be prejudiced when we’ve been living our whole life under prejudice? Like we are immune to prejudice. It doesn’t really affect us. But if we done that to white people, bang, it’d go all around the world, That’s our advantage and also our disadvantage, ‘cos it can fuck us up too.’

Ricky: ‘Have you ever had a blackman come up to you and say, “I’m not prejudiced against you” … get heavy?’

No, I answer.

‘Well it always happens. Some guy’ll come up to you and say, “I’m not prejudiced against you”. Which is really dumb, ‘cos it’s obviously on their minds.’

‘It’s a new music we’re playing now. Next generation people will be singing, ‘Still in the sunlight…’ (From My Eyes). Country & western is the only music they know. You go to a black cabaret and play Your Cheatin’ Heart, and you’ll see half the black people there crying. Because they remember back at that time. They can’t look forward yet.’

It’s hard to dissociate what No Fixed Address do from what they are. But what they do musically is certainly the finest reggae style music to have been produced in this country. I have a tape of three of their songs, Greenhouse Holiday, From My Eyes and Vision. I play it a lot. In fact I’m playing it right now. It’s a third generation tape, being played on a small portable tape recorder but it still has the power to stop me, excite me and leave me wondering. The band admits that it hasn’t quite clicked that they’re making a name for themselves. They’d like to make records, get a big following, go overseas—all the things that most up and coming young groups would aspire to. Bart’s relations tell him that ‘you’re in a world of your own’, but he says they still respect him. They can see how important the band is to him. If No Fixed Address does ‘make it’ they will be an inspiration to a whole people to stand up, stand up for their rights.

The wonder is that it hasn’t happened before. Les tells me about his uncles in Murray Bridge. ‘They can play guitar with their teeth. But all they do is suck on the white lady — metho, spirits.’

Why have most Aborigines played country and western music up til now? I enquire.

‘Memory’, replies Bart. ‘It’s a new music we’re playing now. Next generation people will be singing, ‘Still in the sunlight…’ (From My Eyes). Country & western is the only music they know. You go to a black cabaret and play Your Cheatin’ Heart, and you’ll see half the black people there crying. Because they remember back at that time. They can’t look forward yet.’

Bart estimates there are about twenty black bands in Australia. There’s one in Adelaide called Coloured Stone (‘They’re all my cousins’) who are already following in No Fixed Address’ footsteps by doing the same interstate tour and the recording with Phil Roberts. And then there’s Us Mob who will be on the film album with No Fixed Address. Maybe the day when a black voice will be heard in Australian music is not that far away.

‘We’re just trying to get respected’, says Bart. ‘People who come to see us like the music — but they don’t really understand. What made me write that song We Have Survived was that I realised that the prejudiced people are not going to respect you unless you do something about it. That’s why I did it, ‘cos it’s about time that somebody did it. And we’re gonna keep on doing it’.

‘We have survived /The White man’s world /And you know /You can’t change that’.

∗ ∗ ∗ ∗ ∗

Click here to see the version of Black Man’s Rights featured in Wrong Side of the Road.

Hi Donald – I have a cassette tape of the set the band played at la tribune in 1981 (I think) – it was before Veronica’s time. It’s brilliant.

I am very jealous!

I loved the stories they were a really amazing group at a time when people needed to hear the truth