Australian Rock: The Early Sixties

As the sixties dawned the prospects for Australian rock seemed bright. Johnny O’Keefe, the undisputed leader of the rock pack, was hurriedly preparing for his first American promotional trip. The first crop of Australian rock singers and groups were revelling in the exposure provided by the new TV rock shows like Six O’Clock Rock and Bandstand and the newly introduced Top 40 radio was playing their records.

When O’Keefe hit the States in April 1960 however, he found a scene substantially different to the one that had inspired the first flowering of Australian rock. Elvis Presley had been in the US Army for 18 months and without its figurehead, rock was floundering.

The deaths of Buddy Holly (in Feb 1959), and Eddie Cochran, Chuck Berry’s jailing and the banning of Jerry Lee Lewis didn’t help matters. The payola scandal of 1959, when radio DJ’s were charged with accepting bribes to play certain records, served to further tarnish the rock industry’s already rather unsavoury reputation.

The scene that O’Keefe was trying to crack was firmly back in the hands of the old men of the entertainment industry—the record company executives, radio programmers and promoters who had been shaken by rock’s first surge and who now sought to re-impose their standards on this unruly beast.

The American entertainment industry of 1960 was thus full of young pretty male singers, who were neatly groomed, polite and distinctly unthreatening to parents. Bobby Rydell, Fabian and Frankie Avalon were typical of the genre. They earned the label ‘the Teen Idols’ and were heavily marketed on TV shows, like Dick Clark’s American Bandstand, and hyped on the radio. Their music consisted primarily of sugary ballads and was targeted squarely at teenage girls.

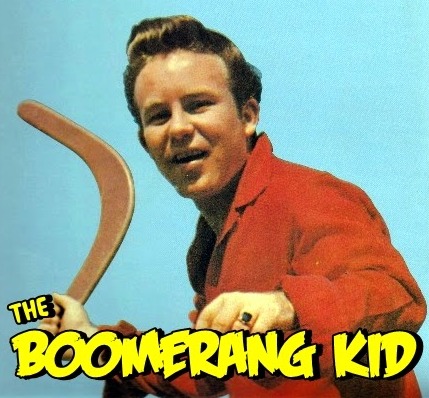

O’Keefe’s wild, uninhibited, exuberant style was the antithesis of this prevailing trend and despite Liberty Records trying to market him as ‘The Boomerang Kid’, it is really not surprising that his first visit proved to be a flop.

Returning home broke, O’Keefe set out on an extensive tour of NSW and Queensland country areas. The tour was a resounding success, filling country film theatres that had been emptied by the advent of television, but the success couldn’t temper O’Keefe’s disappointment. A bad car accident just outside Kempsey in June 1960 sidelined O’Keefe for awhile, but by August he was back compering Six O’Clock Rock and at the end of the year he was touring again in the Victorian country.

A further trip to the States in early 1961 proved as unsuccessful as the previous two and a severely depressed O’Keefe hopped on a plane to London where he had a nervous breakdown and was hospitalised. Rescued from the sanatorium by promoter Lee Gordon, who happened to be in town, he returned to Australia. The ABC axed him from Six O’Clock Rock but within a few months he was hosting his own show, The Johnny O’Keefe Show on Channel 7, (later retitled Sing Sing Sing).

Although O’Keefe continued to have hits right through the sixties and into the seventies, he was never again to dominate the Australian scene as he had in the late fifties and early sixties.

Indeed a curious split, into vocal and non-vocal styles, now occurred in the ranks of the Australian music industry. Instrumental groups in the style of the Shadows, from Britain, started to emerge. In some cases these groups already existed as backing bands for major singers. For instance, the Joy Boys were Col Joye’s backing band when Col did a concert, but as Australia’s rock singers started spending more time doing TV shows, the ‘boys in the band’ started looking for outside work. This they found at local dances where they would perform guitar-based instrumental songs by the Shadows and Californian acts like the Ventures, Link Wray and Duane Eddy as well as their own compositions. The Joy Boys had six instrumental chart hits between 1960 and 1962. This split set the Australian music scene up perfectly for the introduction of ‘surf’ music.

In the northern summer of 1961, the instrumental ‘surf sound’ emerged from the Californian beach scene. According to author Stephen J. McParland, ‘’the first time the term ”surfing” music was used was by Californian Dick Dale to describe his own style of guitar playing. Through the use of reverb and tremolo he attempted to capture the sensation he experienced while surfing.’

The Californian ‘surfie’ lifestyle found fertile ground on the east coast of Australia. As well as the correct climate and geography, the development of the cheaper Malibu board—which was shorter and lighter, being made from fibreglass/balsawood—rendered the sport more accessible to young Australians. It wasn’t long before travelling Australian surfies started bringing back copies of surf records to Sydney. They also brought back a dance called ‘the stomp’, which originated in California, and was tailor-made for instrumental surf music. The stomp was a simple dance which involved giving two thuds on the floor with the right foot, followed by two with the left, then back to the right, all the while flapping the arms loosely or moving them as if paddling a surfboard. The first public stomp held in Australia was at the Manly Surf Club in December 1962.

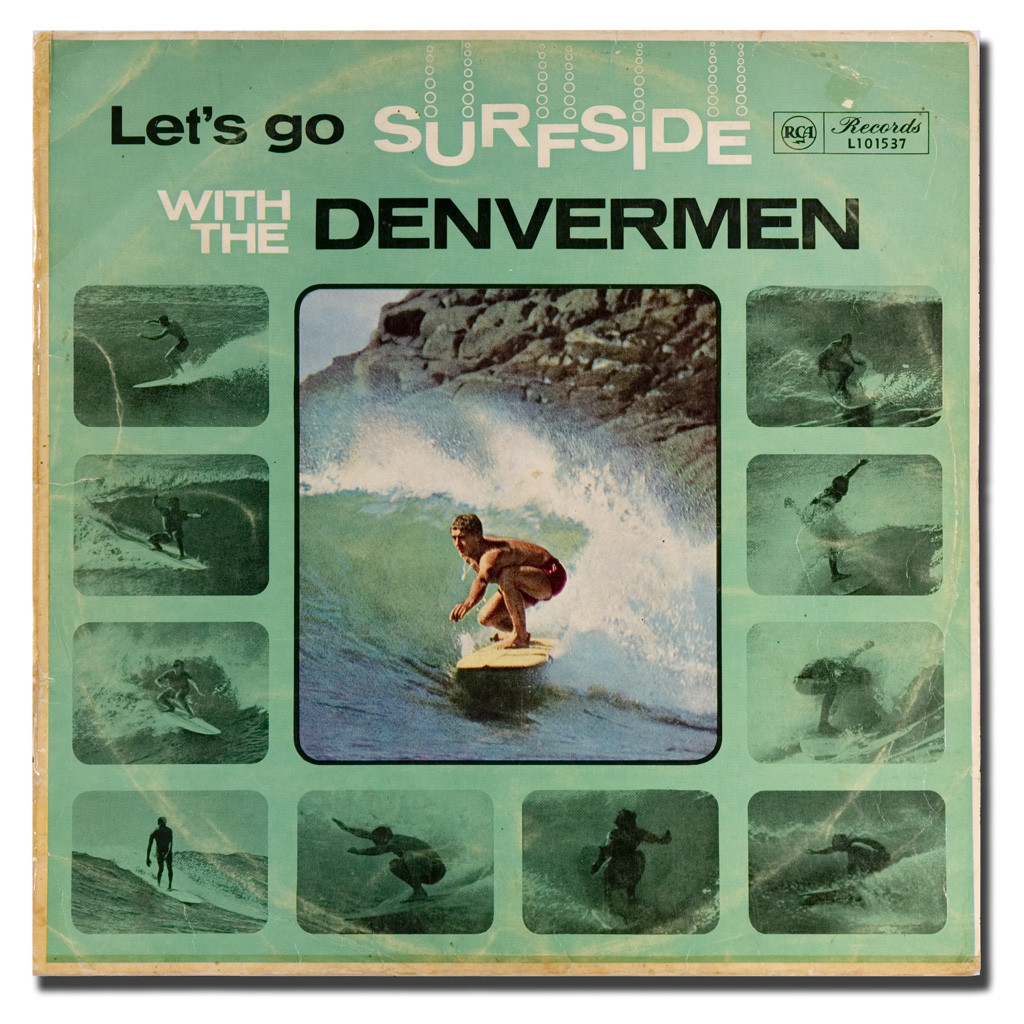

The first Australian surf record was Surfside by the Denvermen, the sometimes backing band for Digger Revell. An instrumental written by Johnny Devlin (himself a former rock performer) it went to No. I on the Australian charts in early 1963. Devlin claims to this day to have been unaware of the Californian surf sound at the time although shortly it would be impossible to ignore.

The second wave of surf music, with lyrics about the surfing lifestyle, was headed by the Beach Boys and Jan and Dean and first hit Australia in early 1963. Perhaps the most memorable Australian surf vocals came from the 14 year old Little Pattie (all 4 feet 9 and a half inches of her!) whose Blond Headed Stompie Wompie Real Gone Surfer Boy and Stompin’ at Maroubra was a double A-side hit in the summer of 1963-64. Most Australian vocalists however couldn’t compete with the brilliant harmonies of the Beach Boys and Jan and Dean.

The two forms of surf music co-existed happily on the charts for the rest of 1963. Surf City by Jan and Dean hit No. I in July and was followed to the top by the Surfaris’ instrumental Wipeout (August). The Sydney-based Atlantics hit No. 1 with the instrumental Bombora; arguably Australian surf music’s finest offering, in September. In the chart of October 2nd 1963, six out of the top ten were surfing songs. Everybody’s Magazine gushed, ‘The surfie music, with its wild compelling beat and the roll of the waves splashing into the songs is the most exciting sound on the charts since the Twist.’ When the ‘Surfin’ Big Show’, featuring the Beach Boys and the Surfaris, was announced to be touring in January 1964 it seemed as though Surfie Heaven had come to earth.

It seems incredible, even now, that the surf sound could have been almost completed wiped out in just a few short months.

It was however—and the reason for its demise was the Beatles. Initial press reports about ‘four young men with stone-age haircuts …’ gave no indication of the upheaval this Liverpool group was about to cause.

Although they’d had some chart success in 1963, by the end of February 1964 the Beatles had four of the Australian top ten and the saturation media coverage that would engulf the nation for the following six months and more was already in full swing. Beatles’ press officer Derek Taylor claimed that the Beatles were the longest running story since World War II—and they were. The announcement that the Fab Four were to tour Australia in June sent shivers of anticipation through the already stricken teenage masses. By the time the Beatles actually arrived, fresh from a lightning two weeks debut US visit, the whole world was at their feet.

Derek Taylor recalled the touchdown at Mascot Airport in Fifty Years Adrift.

‘The storm at Sydney Airport was beyond belief. I had not known rain like it and of course like all sudden unexpected acts of violence, it was a shock to our systems … Great hailstones beat against the windows of the jet and beneath us was a vast wide bouncing lake … The plane touched down, sending huge rippling waves down the runway … Somewhere behind the pounding of the rain and the roar of the engines in reverse there was another sort of noise. A high relentless scream. A scream which went on and on. The fans. Five thousand of them. Drenched, bruised and battered by the rain, taut and jumpy with anticipation, herded by the police. But still there, screaming and still loyal.’

George Harrison wrote later that the tour was like being in a movie. It was the group’s first real experience of mass adulation. ‘We were all new to the fame and yet we did it as if it were completely familiar, as if we’d done it many times before. It was all in the script. It was just a script and nothing to do with us. I don’t even feel like I did it or had anything to do with it.’

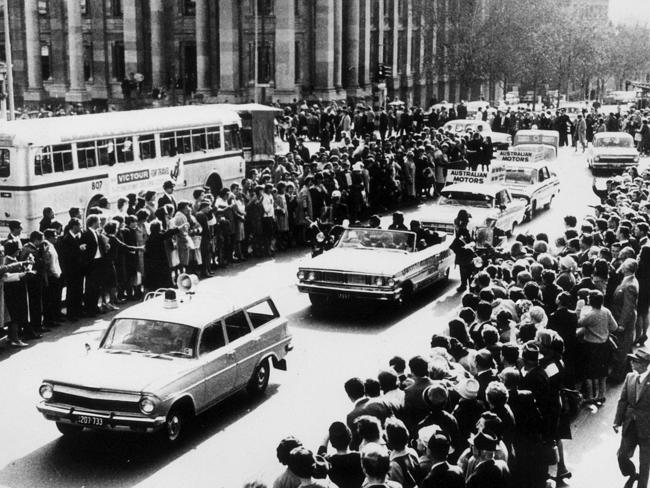

The scenes in Adelaide were nothing short of extraordinary. Over a quarter of a million people lined the streets from the airport to the city to welcome the group. Derek Taylor recalls attempting to explain the event to an American reporter: ‘ “It was like the Messiah come to Australia,” I said, understating as best I could. “Cripples threw away their sticks and blind men leapt for joy.” It was like that. There were so many people of all ages and types reeling and a-rocking with joy that it felt as good as good can be. I had some difficulty in believing I was really here, a material witness to this unprecedented public love affair.’

For the rest of the year Australia reeled under the full weight of the ‘British Invasion’ as group after group came out to Australia and set up camp in the Australian charts. Gerry and the Pacemakers actually preceded the Beatles by a few months, and the Fab Four were followed by the Searchers, Billy J. Kramer and the Dakotas, Peter and Gordon and the Animals. About the only Australian act who managed any chart success in this period were the Aztecs, featuring young Billy Thorpe, who, clad in Beatle-style suits and sporting Beatle-length hair, hit the top of the charts with Poison Ivy in August.

Beatlemania and Merseybeat certainly rejuvenated rock and broadened its audience and if 1964 was an (understandably) quiet period for home grown talent, 1965 proved to be the most exciting year since the first rock wave of the fifties. Recording standards and opportunities also improved in the wake of the British Invasion.

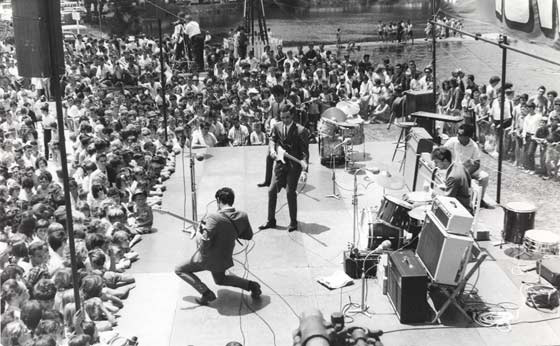

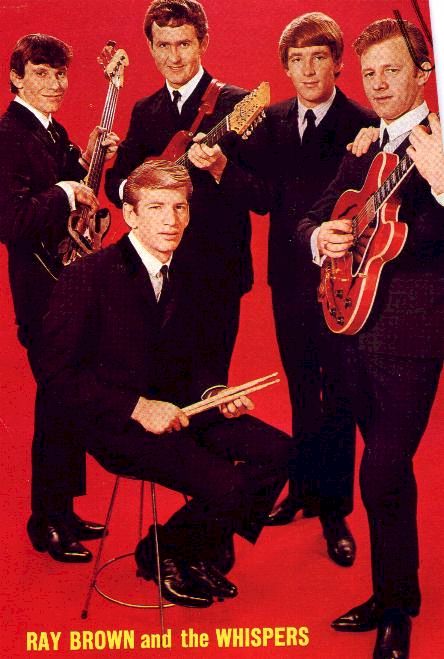

With the Beatles re-emphasizing vocals and vocal harmonies to rock, the instrumental bands of the surf period (many of whom had actually achieved a high level of musicianship by this stage) were forced to bring in lead singers to have any hope of getting live work and recording deals. Sydney’s Nocturnes changed their name to the Whispers and slipped in behind a Hurstville lad by the name of Ray Brown and together saw their first three singles (Twenty Miles, Pride and Fool, Fool, Fool) hit the No. 1 spot in 1965. Melbourne’s Playboys, who had been playing around Melbourne for a few years, acquired Normie Rowe as their frontman and saw their first single (It Ain’t Necessarily So) also hit No. 1. Other acts to break through in this period included Bobby & Laurie and MPD Ltd (both from Melbourne) and Sydney’s Easybeats, who had their first No. 1 in July with She’s So Fine.

The programme manager of Melbourne’s 3UZ noted in August the dramatic rise in the popularity of Australian artists. ‘In January there was only one local recording on the 3UZ Top 40,’ he said, ‘while now there are 17.’

Melbourne, which for so long had laboured in Sydney’s shadow, had gradually developed a local scene, based on Town Hall dances, that far outstripped anything the Harbour City had to offer. By the end of the year Melbourne also had four rock TV shows including the now legendary Kommotion and the Go!! Show (with compere Ian Turpie, whose 17 year old girlfriend was none other than talent contest winner Olivia Newton-John). Brisbane, with the Purple Hearts (featuring a young Lobby Loyde) and Adelaide with the Twilights (featuring an even younger Glenn Shorrock) were also starting to buzz.

In October Billy Thorpe and the Aztecs and Ray Brown and the Whispers, with a host of support acts, set out on a national headline tour—the first time an all-Australian package had attempted the feat.

At the end of the year Maggie Makeig, columnist for Everybody’s Magazine, sounded a note of caution. ‘The beat field is crowded and unwieldy with no definite trends cornering the market. There are now 2000 pop groups with registered names and our population is simply not big enough to support that number.’ Perhaps she just had the Sydney blues, for after a trip to Melbourne in early ’66 she remarked that the southern city was ‘all rush and beat and pop stars’.

1965 was the year that the Seekers broke through on a world level. They were a ‘folk-pop’ outfit who got their start in the coffee-lounges of Melbourne, a folk music stronghold, and slipped away to England on a Sitmar Line cruise ship, playing to passengers to pay their way. They later claimed they had only gone ‘for a look’ and had booked return tickets before they left. By the end of the year The Carnival Is Over was sitting on top of both the British and Australian charts, repeating the success of World Of Our Own and I’ll Never Find Another You.

In March 1966, Easybeats’ manager Mike Vaughan announced from New York that the band had signed an overseas deal with United Artists and that Women, which was on top of the Australian charts at the time, would be released in the US, UK and Europe. Most importantly, he also announced that UA were setting aside a promotional budget of US $22,500 to promote the single. It was a very auspicious omen.

In April the Bee Gees announced they would be going to try their luck in England. Although Barry Gibb had achieved fulsome praise as a songwriter (eighteen other acts had recorded his songs), the trio of brothers had failed to make a big impression on the Australian charts.

In July, the Easybeats flew off to England, after consistent outbreaks of ‘Easyfever’ on their farewell tour around the country. In London they teamed up with producer Shel Talmy, who had already produced hits for the Kinks and the Who, and out of their first session came the classic working class anthem, Friday On My Mind. Released in October 1966, by Christmas it was sitting in the UK Top Ten (as well as on top of the Australian chart). It was Australian rock’s crowning moment of glory in the sixties.

Main pic; The Easybeats in England, late 1966.

∗ ∗ ∗ ∗ ∗

The Early Sixties playlist

∗ ∗ ∗ ∗ ∗

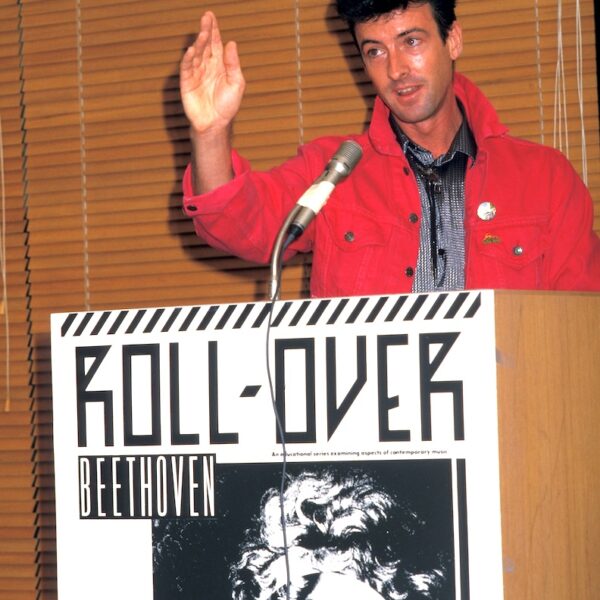

This is part two of my six-part potted history of Australian rock, covering the period from the fifties to the mid-eighties, first published in 1987 in Roll over Beethoven.

Initially produced by Fairfax Magazines, Roll over Beethoven was a project to provide resources for contemporary music education in secondary schools. It was later taken up by AUSMUSIC, which used it as the basis for its music education program.

Interesting post about the period – but as an old surfer from those days I can’t fully agree with the statement “the development of the cheap short board rendered the sport more accessible to young Australians. ” It did, but not until 67 onwards, and definitely not in the early to mid 60s. We were all still riding malibus without leg ropes in those days, and paddling around the break instead of through it. The short board revolution didn’t start till around 1967. Bob McTavish chronicles the story here. http://www.surfer.com/features/the-rise-of-the-shortboard/

Thanks Ian. The history of surfing is not my strong point and I can’t recall my source so I accept my timing is out on this point. I have amended the relevant paragraph to read—”The Californian ‘surfie’ lifestyle found fertile ground on the east coast of Australia. As well as the correct climate and geography, the development of the cheaper malibu board—which was shorter and lighter, being made from fibreglass/balsawood—rendered the sport more accessible to young Australians.” Cheers, Donald

GOOD one, but what was the names of the Denvermen , and who was lead guitar, ?

According to Ian McFarlane’s esteemed ‘Encyclopaedia of Australian Rock and Pop'(2018), the original line-up was Digger Revell, Les Green (lead guitar), Tex Ihasz (rhythm guitar), Peter Burbridge (sax), Allan Crowe (bass) and Phil Bower (drums).

hi don I went to the Sydney stadium in the early 60s and the beachboys starred along with the surfaries , who else was on that show and tour . not the 64 tour with roy orbison but it was earlier. bob manskie

Hi Bob

According to the Milesago site the Beach Boys first tour of Australia was with Roy Orbison, The Surfaris and Paul and Paula in January 1964.