The Malt Whisky Trail: Part I – Speyside

The Scots cannot claim to have discovered the chemical process of distillation, the extraction of alcoholic spirit from fermenting grains, but there are many who would agree that they have perfected it. Whisky, from the Scots Gaelic ‘uisge beatha’—literally, ‘the water if life’—has accumulated over the centuries an aura, a mystique, that sets it apart from other liquors.

The origins of whisky are shrouded in Scotland’s Celtic past. The knowledge of the distillation process was probably brought to Scotland by the Christian missionaries of the sixth and seventh centuries A.D. Brandy, distilled from wine, was most certainly known in the 14th century, but it is not until 1494 that the first recorded example of spirit distilled from malt (i.e. malted barley) occurs. In the Scottish Exchequer Rolls of that year appears the entry, ‘Eight bolls of malt to Friar John Cor, wherewith to make aquae vitae.’ Since this was half a ton of malt and would have yielded around 320 litres of whisky it would seem that production was already well established.

The incidence of the drink in Scotland increased enormously after the defeat of the clans at Culloden in 1745 and the Highland clearances that followed. With most of the able-bodied men off fighting Britain’s European and colonial wars and the women and children left behind being fast replaced by sheep, one of the common ways the crofting families could generate income to pay the rents was from the proceeds of the illicit distillation of whisky.

The British government’s clumsy and high-handed attempts to tax this fiery river proved fruitless until 1823 when, after representations by the Duke of Gordon, finally an Act of Parliament was passed that set the tax and duty at a realistic rate. The amount of legal spirit rose from some 9 million litres to 27 million litres two years after the Act was passed.

The breakthrough years for whisky were the 1880s and 1890s. The vineyards in France had been devastated by the insect Phylloxera Vastareix and as a result brandy was virtually unobtainable. The upper classes in England switched to whisky and it become popular throughout the British Empire.

Despite interruptions caused by the two world wars and the U.S. Prohibition Act of the 1920s, the popularity of whisky continued to grow in the 20th century.

These days there are two main classes of Scotch whisky—blended and single malt. Blended whisky is a combination of malt whiskies and spirit made from maize and corn or other grains. Up to 45 different malt whiskies can be part of a blend. Single malt whisky is made from barley alone and is regarded as the pinnacle of the distillers’ art.

Malt whisky is made from three ingredients; malted barley, yeast and water. The chemical process of distillation is a fairly simple one, familiar to most high school chemistry students. What then is the secret of this golden drink, fabled and praised in song and verse? And what gives rise to the unique character of each brand of malt whisky?

To help unravel these mysteries, there is now a Malt Whisky Trail in the Speyside area of north-east Scotland. Speyside is the prime area of Highland malt whisky production with over fifty distilleries in a small area between Nairn and Banff on the coast and the Grampian Mountains to the south.

Speyside, or Strathspey to give it its Scottish name, is about four hours drive north from Edinburgh. It’s an area of gently rolling hills, some forested, some used as cattle pasture and some left as heather-clad moorland. The River Spey, fed by copious rain and melting snow from the Grampian Mountains, thunders its way through the glen. This abundance of water is one of the things that makes the area perfect for whisky making. Each distillery has its own exclusive water source, often a spring.

The first distillery on the trail is Glenfarclas, situated on open moorland near the spot where the River Avon joins the Spey. Founded in 1836, it was acquired in 1865 by the Grant family of Glenlivet who own it to this day.

The whisky-making process is the same throughout, so the enjoyment of the tours comes down to the history of the distillery and the character of the guide. Andrew at Glenfarclas was young and tall and made a fine sight in his kilt. He dwelt at some length on the centuries-old battle between the distiller and the excise man, pointing out that it would be easier to get through the wall of the warehouse where the whisky matures than to break through the door with its steel bar and twin padlocks (one from the distiller and one from the excise man).

The paranoid attitude of the government has to be set against the history of two hundred years of battles between the Highland distiller and the excise man. Duty was first imposed by the Scots in 1644, but the its evasion became almost a patriotic duty after the Act of Union in 1707 that united the English and Scottish parliaments. With the distillers’ equipment being highly portable and easy to conceal, he led the excise man a merry dance through the Highlands in the 18th century.

The Spey is one of the best salmon fishing rivers in Scotland, although success is not always guaranteed according to Glenfarclas’s Andrew. ‘Some of the whisky inevitably seeps back into the Spey,’ he confided. ‘The locals think this is why the fishing is often lean. The fish are seeing two pieces of bait and making a grab for the wrong one!’

Taking things clockwise, the next distillery is Tamdhu, set in a forest close by the Spey. Tamdhu is one of the few distilleries that still malts its own barley. In this process, the grains of barley are steeped in water for three days, starting the germinating process. They are then spread out on a barn floor and turned regularly until the starch in the grain turns to sugar. When this happens, the process is halted by heating the grains over a peat fire in distinctive pagoda-shaped kilns. The slow burning peat imparts its distinctive aroma to the malted barley.

Once the barley is dry, it is cleaned and then ground into flour. The flour is held in a bin called the ‘grist hopper’ from whence it is fed into a large vessel, the ‘mash tun’, where it is mixed with hot water to extract the sugars. The sweet liquid, called ‘wort’, is drained off while the residue is processed into cattle feed.

From Tamdhu, the trail winds down the B9102 through the quaint village of Archiestown to join the Spey at Craigellachie. From there it’s a few miles to the town of Rothes and the Glen Grant distillery. The fine warehouses withtheir cover of black lichen are the feature of this establishment. The lichen feeds on the two per cent of the spirit that evaporates every year during the whiskey’s maturation process. This two per cent is known as ‘the angels’ dram’.

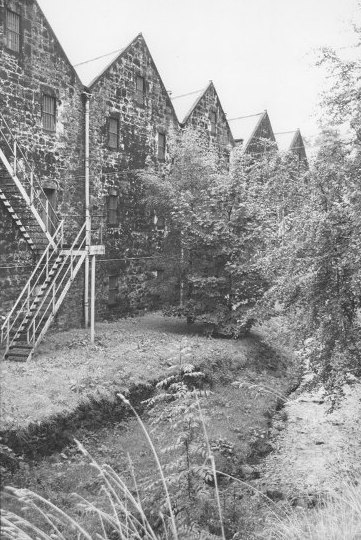

Next on the trail is Strathisla, which claims to be the oldest operating distillery in the Highlands. Founded in 1786, it is reminiscent of an old farmstead.

The Glenfiddich distillery, perhaps the best known name in Highland malt whisky, is situated just outside the small town of Dufftown and adjacent to the 13th century Balvenie Castle. There is in fact a Glen Fiddich (it means ‘valley of the deer’) and a River Fiddich flowing nearby. Glenfiddich bills itself as the home of traditional whisky and much of what goes on there is unchanged since William Grant founded the place in 1887. The water used to make Glenfiddich comes from a spring called the Robbie Dubh (‘Black Robert’) in the nearby Conval Hills.

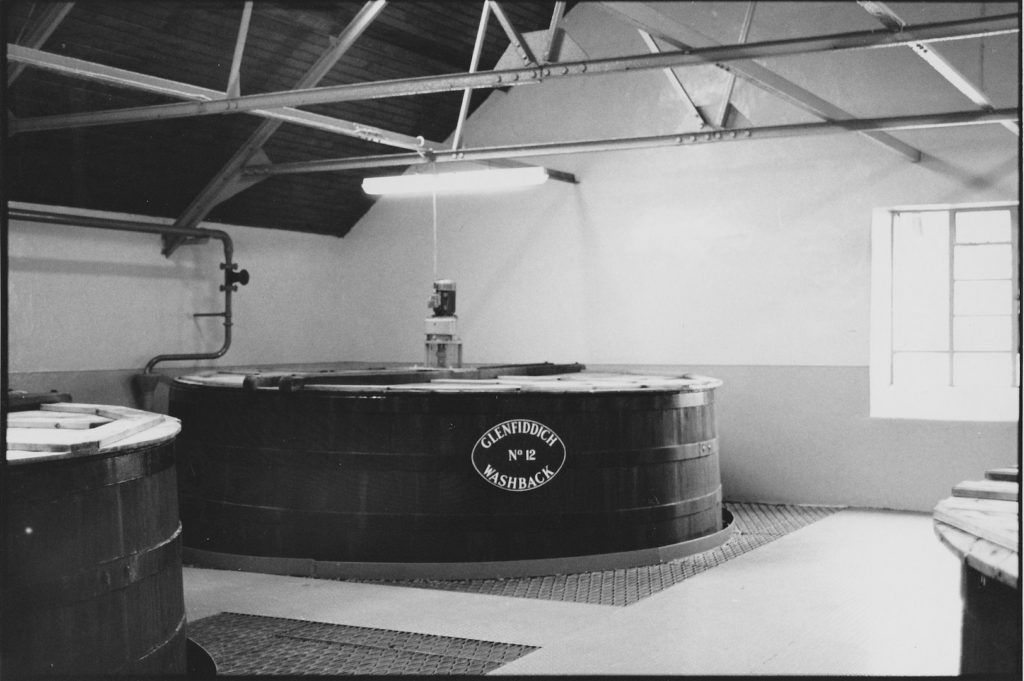

Once the hot sweet liquid (the wort) has been drained from the barley it is cooled and transferred to a large container called a ‘washback’. Here yeast is added and the mixture ferments, often quite violently. At Glenfiddich these washbacks are seventeen feet deep, hold 60,000 litres and are still made from the traditional wood, Douglas fir. Most of the other distilleries have switched to stainless steel, claiming they are easier to clean and are more hygienic. Glenfiddich counters this by pointing out the wood is slower to heat and there’s some bacterial activity associated with it.

The mixture, now called ‘wash’, ferments for 55 hours by which time it is about six per cent by volume. It resembles lentil soup in color and is roughly the strength of strong beer. The heat generated as well as the rising alcohol content of the wash inhibits the action of the yeast.

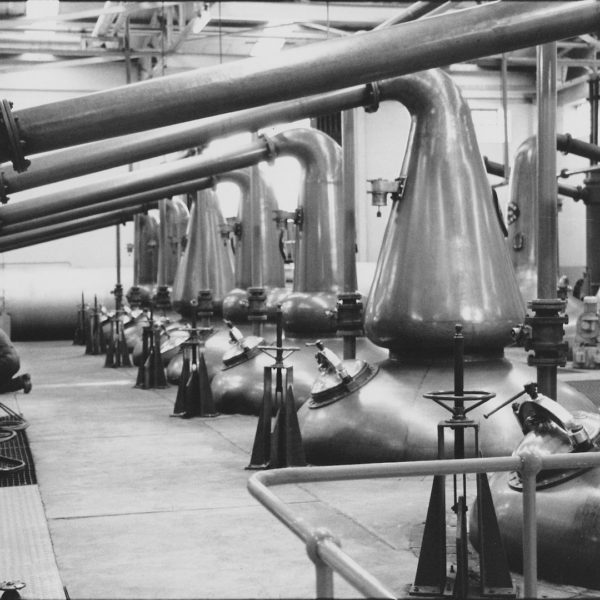

The wash then undergoes two distillations. These are carried out in large copper vessels called pot sills. In the first, the ‘wash still’, the wash is heated from beneath and the alcohol, which has a lower boiling point than water, evaporates first and is collected in a condenser. Called ‘low wine’, this liquid is about twenty-five per cent alcohol and is subjected to a second distillation in the ‘spirit still’. The second distillation is divided into three grades, strong, medium and weak. It is always the medium cut that is used; the other two fractionations go back into the spirit still.

The stills at Glenfiddich are appreciably smaller than those at the other distilleries. Once again this is because they are made to the original specifications of the ones first used by William Grant.

A short drive through Glen Rinnes and some spectacular purple heather-covered moorland brings you to Tamnavulin, one of the newest distilleries in the Highlands. The large stills are oil-fired (Glenfiddich still uses coal) and the washbacks are gleaming stainless steel. water source is near the head of the River Livet and the guide claims with some pride that Tamnavulin has first use of the river’s water.

At Tamnavulin, as at all the other distilleries, the spirit passes through the padlocked spirit safe. The government’s excise man has the key and can arrive at any time to test the contents. At this point the liquid is 70 per cent alcohol by volume and is known as pure British spirit (PBS). It is then diluted with water to 63 pre cent alcohol and put into large oak barrels. Once these barrels were all old Spanish sherry casks; during maturation the spirit would absorb some of the sweetness and color of the sherry from the oak. These days, due to the increasing cost of the sherry casks, a mix of sherry and American bourbon casks are used. The bourbon casks are cheaper and more plentiful. The Scots firms buy them in the States, break them down into lengths and reassemble them for their own use in Scotland.

It takes at least three years in the barrel before PBS can legally be called whisky. Between three and five years some of the malt whisky is sold to blenders. Single malt whisky matures for much longer. Of the whisky trail distilleries, Glenfiddich lies in the cask for eight years, Glenfarclas and Tamnavulin for ten and Glenlivet, the final stop on the tour, for 12 years. At the end of the maturing period all the whisky from all the casks is combined before bottling to ensure uniformity of color and taste—the ‘marrying’ step. The whisky, by now down to under 60 per cent alcohol, is diluted to 43 per cent for export to Australia, Canada and West Germany, while the UK and Sweden have it even weaker, at 40 per cent.

The Glenlivet was the first distillery to take out a licence after the infamous Custom and Excise Act of 1823, but they do admit to making whisky and smuggling it all over Scotland for 77 years beforehand. The plant itself, set amid rolling fields makes a picturesque sight as you come along the road from the village of Tamnavulin. The water for the Glenlivet comes from Josie’s Well at a rate of 227,000 litres a day, although the identity of Josie is lost in the mists of time. Five million litres of the Glenlivet are produced each year; at the moment there are 13.5 million litres of Glenlivet slowly maturing in warehouses on the site.

Neither the two per cent of the alcohol that escapes through the porous oak casks nor the effect of the casks themselves is sufficient to explain the transformation of the harsh PBS into the smooth and mellow whisky spirit. It is thought the pure Highland air contributes in some way to the process, although no-one has yet come up with a convincing explanation of how that might be.

Whisky-making these days is a highly mechanised and efficient industry, with often only six people running the entire operations of a distillery. It is certainly a strong earner for the British government with 17 pounds out of 20 going to the excise man.

My next whisky trail tour will take place in my lounge room. As I was driving solo around the whisky trail, I declined the kind offers of a dram at the conclusion of each tour and picked up minatures instead. One night soon I’ll invite a couple of friends over and we’ll sample each in turn. It’ll certainly save a few lads the airfare. Slainte mhath!

First published in Penthouse Magazine, April 1989.

Postscript: The Whisky Trail survives today, although it only includes three of the original distilleries (Glenfiddich, The Glenlivet and Glen Grant). They have been joined by six newbies.

Scotch whisky is exported to about 200 markets around the world, with the top ten markets by value in 2013 being the USA, France, Singapore, Spain, Germany, South Africa, Taiwan, South Korea, Mexico and Brazil. Total exports were valued at 4.3 billion pounds and comprised 85 per cent of Scotland’s food and beverage exports and nearly a quarter of Britain’s. Exports have increased by 80% in the last 10 years. Sales are increasing in emerging markets such as Russia, India and Africa.

The UK is the 3rd largest market for Scotch whisky. Excise duty and VAT make up 80 per cent of the purchase price of a bottle of Scotch in the UK.