The Malt Whisky Trail: Part 2 – Islay

I’d always fancied getting married in a kilt. And so, when it came my turn to tie the knot earlier this year, it was in full Scottish finery—kilt, sporran and a short black jacket with silver buttons.

The wedding was a tremendous success. The bride was as beautiful as a fairy princess (I must admit to a slight bias I fear), the bagpipes rent the air, the ceremony was short but sweet, the meal was excellent, the speeches were sincere and to the point and the toasts were drunk with the very best Scotch whisky.

Ah, you may ask, what whisky would a Scotsman drink at his own wedding?

Most Scots, I think, would plump for a smooth Highland single malt like Glenfiddich or Glenlivet. Now, I’ve got nothing against the Highland malts. I’ve tasted more than my fair share of them and by and large they are a marvellous spirit. But my favourite whisky is not counted amongst them.

Bowmore 12-year-old single malt from the Hebridean island of Islay is my preferred dram any day of the week. I could wax lyrical about the sensation of angels dancing on your tongue or the way the spirit seems to dissolve in your mouth and waft warmly down the gullet, but I think I’ll leave these things for you to discover yourself.

My bride has travelled widely, but had never been to Scotland. So we decided to spend part of our honeymoon in the land of tartan and heather. And whisky. Since we were going there I entreated, wouldn’t it be great to make a brief pilgrimage to the holy shrine of Bowmore.

The Isle of Islay harbours the second greatest concentration of malt whisky distilleries in Scotland. (The greatest number are to be found in the Speyside area of the Highlands.) The distinctive feature of Islay malts is their strong peaty flavour. Peat is compressed heather and mosses, up to 5000 years old, and when burnt gives off a distinctive aromatic smoke. All malts display a certain amount of peatiness, from the peat smoke that is passed over the germinating barley grain, but the malts of Islay have the strongest flavour of all.

Islay is reached by ferry from Kennacraig on the Kintyre peninsula about 160 km west of Glasgow. After about a week of driving around the Highlands, visiting various branches of the Robertson and Maclean clans, we arrived at the Kennacraig terminus late on a Sunday morning. The car ferry to Port Ellen takes about two and a half hours.

Port Ellen, the island’s chief town, is a rather dismal little place and the road north to Bowmore runs through some even more depressing country. In a land famed for its mountains, it came as rather a shock to drive across such a flat, barren expanse of peat bog. My other half was not is the best of humour when we reached Bowmore.

We had booked into a hotel in Bridgend, a few miles north of Bowmore. Bridgend, we discovered, consisted of the hotel, a shop, a couple of houses and a bus stop. At least the sun was shining. Otherwise I think an immediate divorce might have been on the cards.

The Paps of Jura

The previous night, in Oban, I’d tasted an unfamiliar Islay malt by the name of Bunnahabhain (pronounced Boo-na-ha-venn). The Bunnahabhain distillery was situated at the north end of the island, near the island’s other ferry port, Port Askaig. I suggested we take a spin up there before dinner. The main road was fine, with gently rolling scenery rather more varied than the south of the island, until the turn off a couple of miles before Port Askaig. From there the road to Bunnahabhain was nothing more than a precipitous goat track. The views across the narrow Sound of Islay, to mountains of the neighbouring island, the breast-like Paps of Jura, were spectacular, but is was a nerve-jangled couple who eventually shuddered to a stop beside the distillery.

Bunnahabhain distillery

Like all the distilleries on Islay, Bunnahabhain is on the sea. Unlike the others, the water it uses comes from streams that tumble over hard granite rocks. As a result, it was the least peaty taste of the island’s whiskies.

Back at the hotel, the absence of local eateries meant dinner in the bar. Let me tell you, it was not good. We retired to the room and after a full and frank exchange of views, a decision was made to cut short the Islay sojourn and depart the island on the following afternoon’s ferry.

Fortunately, there was a morning tour of the Bowmore distillery, so fortified with porridge and eggs, we paid the bill and bade farewell to Bridgend. A word of warning to intending visitors, Take plenty of cash. Credit cards don’t seem to have penetrated to the hotels of the Western Isles yet.

So chastened and penniless (a true pilgrim!) I finally entered the hallowed portals of the Bowmore distillery—source of the best whisky in the world.

The distillery was founded in 1779. The present owners, the Morrison family, acquired the business in 1963 and have shifted its emphasis from the production of bulk whisky for export and blending to that of mature bottled whisky. The 12-year-old Bowmore single malt wasn’t introduced until the mid 1970s.

The distillery comprises a collection of whitewashed buildings at one end of the main street of the village of Bowmore on the shores of Loch Indaal. All the processes of whisky production are carried out on site, including the germination of the barley grain. Many distilleries buy in pre-germinated grain these days.

The barley comes from Dornoch, near Inverness, and on arrival is soaked, or steeped, in water and then spread on a malting floor to germinate. There are three such floors at Bowmore and during the seven days it takes for the grain starch to turn to sugar, the barley is raked over every four hours. The tour guide asked for a volunteer to demonstrate and I put my hand up. My wife took photos, which was probably the high;light of the day for her (not counting getting back to the mainland that evening).

At the end of the seven days, the barley is transferred to a drying floor where germination is halted by the passing of hot air over the grain. At Bowmore they alternate between peat smoke and clean hot air in twenty hour shifts. When dry, the grain is ground in a mill to form grist, a peaty-flavoured rough barley flour. The three floors of barley make 13,500 bottles of whisky.

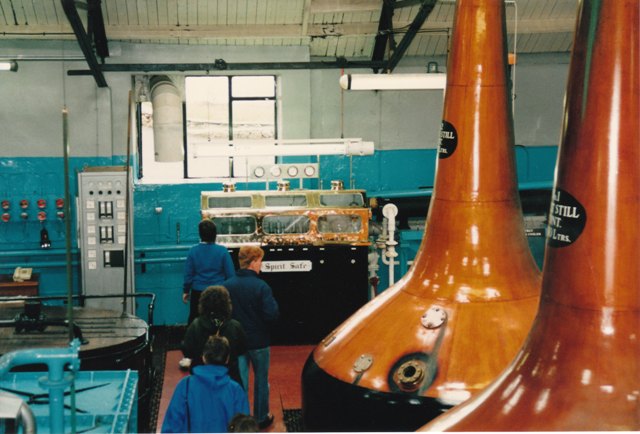

The stills at Bowmore distillery

The grist is mixed with hot water to dissolve the sugars. A sweet liquid is drawn off and yeast is added to convert the sugars to alcohol. The fermented liquor is like a barley beer and is known as wash. The wash then passes to the still house where the mixture passes through two stills and 20 degree over proof alcohol is extracted. This spirit is diluted with water to 11 degrees over proof and then placed in oak barrels to mature and mellow.

At the end of the tour, we were offered a dram on the house. Unfortunately it didn’t seem to mix too well with the cough mixture I’d taken after breakfast to combat the cold I’d picked up a few days earlier in Fort William. Consequently, the next hour saw me reduced to a trembling wreck piled into a tiny blue Austin rushing south to view the two mega-peaty monsters of Islay whisky, Laphroaig and Lagavulin. My wife, who had been temporarily placated by the cheeriness of the Bowmore tour guide, drove with a frosty intensity.

Laphroaig distillery

As we drove across to the peat moor to Port Ellen, I reflected on the different peatiness of the Islay malts. Bowmore gets its water from the River Laggan, which descends from the heights of Beinn Bhan. Laphroaig and Lagavulin get their water from streams that meander across the southern peat. As well as the peat smoke that permeates the grist, the water itself must impart a flavour to the end product

And the final element in the whole puzzle is the air. Cool moist air continually washes over Islay from the North Atlantic. As well as providing a fresh and untainted atmosphere for the whisky to breathe during maturation, these breezes assist the malting, brewing and distilling by discouraging harmful bacteria and fungi.

Lagavulin distillery

Laphroaig and Lagavulin are both on the road east out of Port Ellen. By the time we had reached Laphroaig, I had recovered sufficiently to clamber from the car and take a few photos from the pebbly beach. In keeping with its whisky, Laphroaig is set on its own and has rather a severe and forbidding exterior, with nothing resembling a visitor’s centre. Lagavulin, in a small village about a mile further on, has a slightly more friendly aspect and does have a centre but tours are by appointment only.

‘Only one more to go,’ I offered jocularly as I climbed back into the car. ‘Or,’ noticing the look of withering scorn speeding my way from the direction of the driver’s seat, ”we could head straight for the ferry.’

‘No, we’ve come this far—you may as well see one more,’ came the reply. ‘Thanks sweetheart,’ I muttered weakly as we headed north, back through Bowmore and Bridgend to Bruichladdich, the most westerly distillery in Scotland.

Bruichladdich distillery

Set on the other side of Loch Indaal from Bowmore, Bruichladdich is a small village clustered around the distillery. A large sign on the distillery proclaims, ‘No Admittance Except On Business’. The view back across the loch to Bowmore is rather nice.

‘Nice view,’ I commented. My wife glanced up from the large paperback resting on the steering wheel of the small blue car. ‘Hrrrmmph,’ came the reply.

‘OK—L.B.T.T.S.,’ I said. ‘What?’ she asked suspiciously. ‘Let’s blow this taco stand,’ I replied blithely.

So we laid rubber at Bruichladdich and headed back to civilization. As we drove, I reflected once more on the perfect drink produced by this less than perfect place. Maybe, as my good friend Andy says, all the best liquor does come from inhospitable places.

The four elements of the ancients, earth, water, fire and air come together in harmony in whisky. Barley from the earth, water from the stream, fire from the peat and air from over the sea. It’s no wonder the Scots call it uisge beathe, the water of life.

And the great thing is, you don’t have to go to Islay to enjoy it.

Written 1990, previously unpublished.