If you’re going to San Francisco …

We’re on the sidewalk at the west end of Waller St, a stone’s throw from Golden Gate Park and the final stop of our two-hour walking tour of San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district.

Our genial tour guide Kurt, a chubby, moustachioed, local comedian and film maker points out a converted firehouse across the road at number 1575 where in April 1967, representatives of the local alternative community held a press conference to announce the formation of the Committee for the Summer of Love. They called on the city of San Francisco to welcome the rising tide of young people already flooding into the area to check out the widely-publicised ‘hippie’ scene.

‘What they were saying,’ says Kurt, ‘was that they could cope. Of course, they couldn’t. You know the Scott McKenzie song that came out shortly after —‘If you’re going to San Francisco/ be sure to wear some flowers in your hair’? What it should have said was—‘bring medical supplies and sturdy footwear!’ ’

Haight-Ashbury is a district about five km west of Union Square and easily reached via the city’s excellent public transport system. It was established in the late 1800s as a holiday resort for rich San Franciscans because of its proximity to the attractions of Golden Gate Park. The well-to-do built ornate, decorative multi-storey wooden houses known as ‘Victorians’. It escaped the devastation of the Great Earthquake of 1906, but subsequently fell into slow decline. By 1965, it was a poor neighbourhood, full of run-down Victorians. These were large enough to share and coupled with their cheap rents made the area ideal for communal living and popular with students from nearby San Francisco State College.

There was another group that found the area attractive. These were bohemian-minded kids who had developed a taste for mind-altering drugs. Of these, marijuana and amphetamines were well known and had been staples of the literary movement known as the Beat Generation, which had flourished in the North Beach area of San Francisco in the 1950s. But there was a new type of drug increasing in availability and popularity, the psychedelic drug. Chief among this type was LSD or acid—a drug that was perfectly legal at the time.

This new psychedelic generation was interested in art. psychology and eastern religions like Zen Buddhism and Taoism. The Beats called them ‘hippies’ or junior hipsters, a put-down term to which the kids took no offence and calmly adopted as their own.

In the period 1965 to 1968, the hippie movement changed the Haight-Ashbury district from an interesting local scene to a national curiosity to an international phenomenon.

In the period 1965 to 1968, the hippie movement changed the Haight-Ashbury district from an interesting local scene to a national curiosity to an international phenomenon. And then, its attractions having been proclaimed by the mass media and having hit a chord with a generation disillusioned with mainstream society and America’s war in Vietnam, it was totally overwhelmed by an influx of young people. The neighbourhood dived, becoming for many years a ‘heroin-infested slum where someone could get knifed for a bag of groceries’, according to Charles Perry in his history, ‘Haight-Ashbury’.

But somehow it survived and is now a prosperous, safe and thriving area with Haight Street boasting a bustling array of shops, souvenir outlets, restaurants and bars. Among these and not to be missed is the cavernous Amoeba Records at the western end near the park where you can pick up not only music but also the distinctive posters advertising concerts from the original psychedelic era.

We meet up with Kurt for the ‘Summer of Love, Winter of Discontent’ tour on a sunny Sunday winter afternoon at the Peace Cafe on Haight St. Kurt says he usually has about a dozen people on the tour, but today there’s just me and my 17 year old son Calum.

We head east on Haight Street and take a right up Belvedere one block to Waller Street. Here we start to see the first of the beautifully restored wooden Victorians that are such a feature of the district. With their brightly painted exteriors, gables, turrets, balconies, bay windows and decorative panels, they are full of individual character and some are simply stunning.

Kurt has some small speakers slung around his neck connected to a small iPod and at various points in the tour he stops to play a snatch of music to illustrate a point or to ask a question – the correct answer earning a ‘good trip’ or ‘bad trip’ card as a reward. At the end of the tour the person with the most good trip cards wins a prize.

715 Ashbury Street: HQ of the San Francisco Hells Angels and directly opposite the Grateful Dead’s pad in the period 1966-68

The first major landmark on the tour is a short walk up Ashbury Street from Waller. The Grateful Dead lived at number 710 in the period 1966-68, a period when they played or participated in pretty much every significant event in the district. Across the road, at number 715, was the headquarters of the San Francisco Hell’s Angels. The Dead had become great friends with the outlaw motorcycle gang at parties held at novelist Ken Kesey’s ranch south of San Francisco. The Dead were the house band at the parties known as Acid Tests. Guests dropped LSD and found themselves subjected to a range of unexpected, puzzling situations or ‘pranks’. This practice earned Kesey’s followers the name the Merry Pranksters.

A little further along Waller Street, at 1350 is the All Saints Episcopal Church. This unremarkable looking church doubled as the headquarters of the Diggers in the period. The Diggers were an edgy, often confrontational splinter group from the San Francisco Mime Troupe, a theatrical company that sought to combine avant-garde theatre with radical politics. As well as carrying out guerrilla-art events like the ‘intersection game’ in which pedestrians formed geometric patterns and jammed the traffic in Haight Street, the Diggers issued a steady stream of caustic broadsides but also became a de facto social services unit, organising daily free food in the Panhandle area of Golden Gate Park and crash pads for homeless runaway youths.

The tour takes a left down Masonic Avenue, past an unrenovated Victorian that gives us an idea of what the whole area looked like in the mid-sixties and back onto Haight Street. Heading east we pass the building that housed the San Francisco Oracle, the psychedelic newspaper of the Haight-Ashbury. The ground floor is now a second hand record store. The paper’s founder Allen Cohen recalled later, ‘It wasn’t difficult in 1966 to work occasionally, sell marijuana or LSD intermittently, and thereby earn a living for oneself and friends. One could devote most of one’s time to art, writing or music, experience the enhanced and ecstatic states of mind accessible through the use of marijuana and LSD, interact with other artists, get high and talk until the sun’s rays erased the night. In these years, and in these ways the particular styles of music, art, and the way of life identified with the Haight, the 60s and the Hippies developed. ‘

We stroll down Haight Street past Buena Vista Park on the right. The oldest park in San Francisco, it is set on a steep hill with plenty of foliage. Just past the park, we turn left into Lyon St and go down the hill towards the Panhandle, a narrow strip of Golden Gate Park that thrusts a mile or so east of the main park. In 1967, Janis Joplin, lead singer of one of the main bands of the time, Big Brother and the Holding Company, lived in apartment #1, 122 Lyon St, one house back from Oak Street which borders the park (pictured below).

On 6th October 1966 the state of California outlawed the sale and possession of LSD. To mark the occasion, the SF Oracle organised a ‘Love-Pageant Rally’ in the Panhandle at the corner of Masonic and Oak. This was the first San Francisco outdoor rock and roll happening. It was billed as a celebration of the psychedelic life —not a protest —and a crowd variously estimated as between seven hundred and two and half thousand attended to listen to the Grateful Dead, Big Brother and others play. The event was widely covered by TV radio and press and served as a model for the much larger Be-In held at the Golden Gate Park Polo Fields in January 1967. The Be-In, attended by an estimated 20,000 people, was an attempt to forge an alliance between the hippies and the radicals in the anti-Vietnam War movement based at the University of California at Berkeley. It was the Be-In that really brought the Haight-Ashbury phenomenon to international attention.

From the park we walk back up Ashbury Street to the iconic intersection with Haight Street that gives the district its name. After the obligatory photo, we walk west along Haight to the intersection with Clayton St, the location of one of the community institutions that survived not only the fall of the hippie era but everything else since —the Haight-Ashbury Free Medical Clinic. The clinic has inspired around 500 others across the USA, providing them with an open-access model different to that of traditional American charity clinics with their religious connections.

The penultimate stop on the tour is a rather nondescript house at 636 Cole St, between Haight and Waller. ‘Which ex-convict lived here in 1967 writing songs and trying to get them recorded?’ Kurt asks. Calum shakes his head. ‘Charles Manson?’ I venture. ‘Correct,’ says Kurt. ‘Here’s your card. It’s a good trip. Fifty per cent off at the Free Store!’ He then plays an extract of one of the demos that Manson recorded. Somewhat surprisingly, it’s not too bad.

While the Haight-Ashbury tour includes a mix of musical and community landmarks, it’s an interesting fact that there were no music venues in the district.

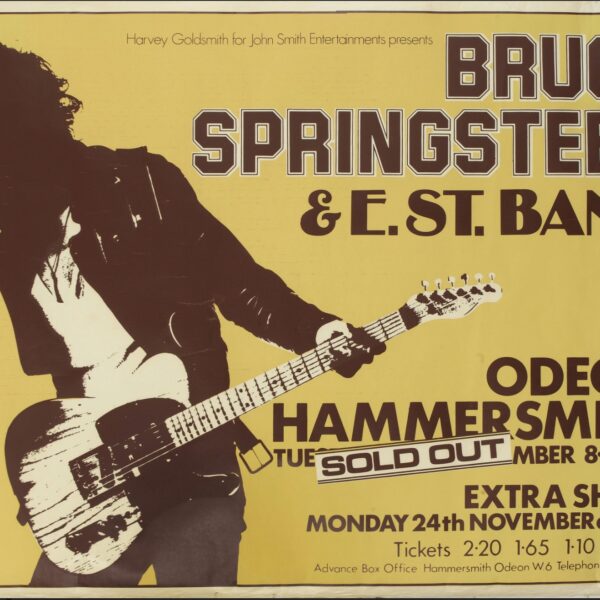

While a number of San Francisco venues played host to the local bands of the day (the Matrix, the Longshoreman’s Hall, the Avalon and Winterland) there’s no doubt that the most prominent and influential was the Fillmore Auditorium at 1805 Geary Boulevard, in the Fillmore District. The previous night, Calum and I had headed out to the Fillmore. We had tickets for Bill’s Birthday Bash, a benefit for the Bill Graham Memorial Foundation. Graham, a former business manager for the SF Mime Troupe that also spawned the Diggers, started putting on performances at the Fillmore in early 1966 and by the time it closed its doors in July 1968, it had played a significant role in ushering in the age of rock that replaced the mid-sixties pop triumph that was Swinging London.

The who’s who of rock trod the boards at the venue, refurbished to its mid-60s mode and reopened in 1994 in fulfillment of one of Bill Graham’s final wishes (Graham, who became America’s leading tour and concert promoter, died in a helicopter crash in 1991). The honour roll is captured in the Fillmore’s distinctive psychedelic concert posters which are on display in the high-ceilinged mezzanine-level bar of the auditorium today. Those featured on the walls include the Jimi Hendrix Experience, Cream, Them, the Doors, the Who, Pink Floyd, Donovan, Procol Harum, the Incredible String Band, the Byrds, the Animals, Traffic and the Move, as well as all the local luminaries — Jefferson Airplane, Big Brother and the Holding Company, Blue Cheer, Quicksilver Messenger Service and the ubiquitous Grateful Dead. And in keeping with the venue’s location in San Francisco’s predominantly black Fillmore district, there’s a significant presence of black performers including Chuck Berry, Bo Diddley, Otis Redding, Albert King, B. B. King, Taj Mahal and John Lee Hooker.

Many of the original Fillmore traditions are carried on to this day. One is a large tub of free apples for concert goers positioned at the top of the two flights of stairs at the entrance.

Another is a “greeter”, a staff member who welcomes each guest as they enter (“Welcome to the Fillmore!”). The main auditorium features a dance floor with a raised stage, a balcony bar running the length of the hall on the left side and ornate chandeliers adorning the ceiling. With a capacity of 1200 and a number of separate areas, apart from its history, it’s a pretty decent mid-sized venue.

The headline act on the night was the Funky Meters, the latest incarnation of the Neville brothers, New Orleans’ first family of funk, once managed by Graham. Also on the bill were Bonnie Raitt, pianist Marcie Ball and the San Francisco Mime Troupe—still going strong!—with a skit about the handover of U.S. political power featuring Dick Cheney and Sarah Palin.

Former Graham sidekicks Bob and Peter Barsotti entertained the crowd with anecdotes and war stories and former Winterland manager Jerry Pompili reprised his MC role. Graham’s sons Alex and David also took the stage to explain the mission of the Foundation, which is to give grant in the areas of music, the arts and education.

As many in the crowd in the auditorium lifted their iPhones aloft to snap pictures of the event, I remarked to Calum, ‘Some of these people look like they were here in its heyday.’

Looking around at the many grey-haired and grey-bearded Jerry Garcia lookalikes, he shot back, ‘Some look like they never left!’

(Written 2009, previously unpublished)