Scotland 2018: a magical sixties birthday tour

If it had all gone smoothly there wouldn’t have been any stories to tell, would there? Despite the challenges and hurdles along the way, our three-week tour around the Scottish Highlands was a marvelous and memorable experience.

The first challenge was getting there. Once she’d decided she wanted to mark her admission into the 60s club with a trip back to Scotland, Di found a reasonable three-leg business class fare. On paper it sounded pretty good—Sydney to Kuala Lumpur on Malaysian Airlines, a four-hour stopover, then Oman Air to Muscat and Manchester.

The flights themselves were fine, but the security—man. Every time you went to get on a plane, even as a transit passenger, the queuing, the screening, the passport checks. I said to Di at one stage—the terrorists have won. They’ve just made it too unpleasant. ‘What was I thinking?’ she replied. ‘If I ever suggest anything like this again, just say no!’

Manchester

Eventually we landed in Manchester. It was evening and the airport was quiet. We jumped in a taxi and headed for our hotel, the Abode, a converted linen warehouse just up the road from the main railway station, Manchester Piccadilly.

The room was quite groovy, with retro industrial fittings and a large image on a feature wall, but when we put the air-conditioner on (it had been a warm day in Manchester) it created a waterfall-effect in the doorway to the bathroom. We reported this to chirpy Steve on reception, who found another room. Except in this one the air con didn’t work at all. A third one was located but its double bed resembled a marshmallow. By this stage, having just been in the air for approaching thirty hours and enduring all those damned security checks, we decided to cut our losses, grab some extra towels and go back to the original waterfall room. The next day the manager upgraded us to a suite with a new brand new king sized bed. Much better.

Manchester struck me as a real hodge-podge of the old and the new. The Northern Quarter, within walking distance of the hotel was a pretty intact area of 19th century red brick buildings, many of which were William Blake’s ‘dark satanic mills’—the original cotton factories and warehouses of the Industrial Revolution. Some of them had been converted into cafes, bars and restaurants. Ezra and Gil on Newton Street, a favourite for scruffy hipsters, had a laid-back atmosphere and was great for breakfast and coffee while the downstairs restaurant at Tariff and Dale, on the corner of Tariff Street and Dale Street (natch), had an excellent menu and reasonable prices. We also discovered Mackie Mayor, the old meat market with a wrought iron and glass roof that has been sympathetically converted into an open space food court, with restaurants, bars and cafes.

I thought I’d been pretty clever by buying well in advance our GBP11.90 train tickets on TransPennine Express to Glasgow, where we planned to meet up with our friends David and Carmel from Sydney, and pick up a hire car to tour around the Highlands. It was walking distance to the station, so we rolled our suitcases up the road, got to the main entrance, looked up at the big board to be confronted with the message ‘11.22 Glasgow Central CANCELLED.’ Oh shit.

Leaving Di to mind the luggage in the crowd milling around the big board, I joined the long queue at the information office. When eventually I got to a window, I waved our tickets at the lady there, who responded in a calm Coronation Street accent, ‘Your train isn’t COMPLETELY cancelled (pause, looking at her screen) … it’s waiting for you at Preston. And (looking at her watch) there’s a train leaving platform 14 in four minutes that will get you there.’ Oh shit.

I dashed out, grabbed Di and we raced towards the platforms. Of course, platform 14 was right at the opposite end of the station and all the moving walkways were broken and there was a big queue for the lift down to the platform … but we got there and a train was waiting so we threw our cases in and jumped on just before it pulled away. We looked at each other. Phew!

An announcement came over the PA. ‘This is the train to Llandudno, stopping at Manchester Oxford Road, Newton-le-Willows, Warrington, Chester, Rhyl …’ Uh-oh.

A man who looked like he could be a guard and had seen us scramble on was standing in the entrance to the carriage. ‘Is this the Preston train?’ I blurted. He looked at me pityingly. ‘No.’ Oh shit!

He looked at his iPad. ‘The Preston train is just behind us. We’ll be stopping at Oxford Road in a minute. It stops there too. You can get off and catch it there.’ Looking at our suitcases, he added mournfully, ‘I’m not sure what platform it stops at. And there are no lifts there …’ Phew … I think …

We got off and fortunately the Preston train stopped at the same platform. We got on and collapsed into a couple of seats, our hearts racing. But the drama wasn’t over. When we got to Preston, we got off and looked up at the big board. The train to Glasgow Central was leaving from platform 4 in 5 minutes. We were on platform 5, so we rolled our cases down the ramp, along the tunnel and up the ramp to platform 5. I looked up at the board again and noticed at the end of the message for the Glasgow train the words ‘Virgin Trains’ in brackets. Uh-oh.

I went to the information window and waved my tickets. ‘We’re on the TransPennine Express to Glasgow. They told us in Manchester it was waiting here,’ I said breathlessly. The Virgin Trains lady looked at her computer. ‘That’s your train on platform 5,’ she said. ‘It’s due to leave in (she looked at her watch) one minute.’ I ran to the edge of the platform and waved across to a guard standing at the end of the train on platform 5. He turned away. Then an announcement, ‘The TransPennine Express service to Glasgow is delayed due to signal failure.’ The very swish Virgin train whooshed in. Di and I looked at each other. ‘Come on, let’s go.’ We jumped on.

All the way to Glasgow we couldn’t relax, tensely expecting a ticket inspector to come along and discover the two stowaways in carriage B. But as we left Carlisle, the last station before the border, Di breathed out and said, ‘At least they can’t throw us off.’ ‘Hmmm—we could still get pinged at the barrier at Glasgow,’ I said. But our fears were groundless, as there was no ticket check at all when we got off the train.

Of course, things were a lot better once we got to Scotland. If only she could shake off the dead weight that England has become (sigh).

Glasgow

We had booked at the Destiny Scotland apartments in Nelson Mandela Square, right in the centre of the city and a stone’s throw from Buchanan Street. Brilliant location and the apartment was a great conversion in a Grade A listed building.

My cousin David and his partner Damien motored up from Elvanfoot in the Scottish Borders to join us for dinner at Fratelli Sarti’s, one of Glasgow’s finest Italian nosheries. David and Damien spoiled us with unexpected presents of a tweedy nature—hipflask and purse—and a jolly time was had by all.

In the morning we strolled down Sauchiehall Street to the newly refurbished Mackintosh at the Willow tea rooms at number 217. These are the third Mackintosh tearooms, joining the ones at the corner of Hope and Bath Streets and 97 Buchanan Street, but definitely the flagship of the fleet. While a delight to the eye, Di found the scone we had with our morning tea rather disappointing— veering dangerously close to shortbread territory. Nae-sae-bonnie Prince Charlie and his new missus officially opened the establishment the following day.

We had been invited to lunch at the apartment of writer Ian Mitchell. When I was researching the life of John Maclean in 2015 for a film script I was working on, Ian kindly showed me around some of the sites of Glasgow associated with the renowned socialist of Red Clydeside. Ian’s apartment was in the Park District, an enclave of Georgian terraces just to the west of the city. The area is on a hill overlooking Kelvingrove Park and the University of Glasgow and is reminiscent of Bath or Edinburgh New Town. Many of the buildings were used as offices in the latter half of last century but the trend is for them to be converted back into residences.

Ian’s place was on the top floor of a three-storey walkup with a grand entrance hall and staircase. From the apartment windows you could see the tenements of Govan—just across the Clyde, but a million miles from this architectural splendor. As well as having written a number of books about walking through areas of Glasgow’s industrial past, Ian is a keen mountaineer and has written many books about that subject as well. After a very pleasant lunch, we left with a copy of his latest, Encounters in the American Mountain West.

Ian guided us down the hill through Kelvingrove Park, past the statues of Lister and Kelvin and we had a quick look inside the vast Kelvingrove Museum before hopping on the subway at Patrick. We had dinner that night in Merchant City at another famous Glasgow eatery, Café Gandolphi with our Sydney friends David and Carmel—our travelling companions for most of the next fortnight.

Fort William

I’ve driven from Glasgow to Fort William each year since 2015, and every time I’ve gone over the Erskine Bridge from Glasgow Airport, through Dumbarton and then up the west side of Loch Lomond.

The worst stretch is from Tarbert, half way up, to the Drover’s Inn at the head of the loch. The very narrow, busy road runs between the water to the right and rock walls to the left, and there is nowhere to stop and pull over.

So, this time I thought we’d go up to the east of Loch Lomond, through Doune, Callander and the Trossachs. And very pleasant it was, with pretty country and a good road. Callander also had the best second-hand bookshop I’ve found in all of Scotland. I picked up a biography of miners’ leader Bob Smillie and a collection of writings by Hamish Henderson, writer of ‘John Maclean’s March’, the song that set me off on my current quest. Nine quid the pair—bargain.

From Callander we drove alongside Loch Lubnaig, through Glen Ogle and then after a left turn, along Glen Dochart to Crainlarich where we rejoined the A82 for the journey north to Glencoe and Lochaber.

By the time we decided to come to Scotland, my cousin Joan at The Grange was fully booked on Di’s actual birthday, so she booked us in next door for a night. Crolinnhe was a similar whitewashed Victorian villa, and while very comfortable, the bathroom was a bit disconcerting. Everything—taps, dunny, shower—seemed to work by remote sensor so it was a bit like walking into a set from a James Bond movie.

Joan and hubby John couldn’t really get away so Di’s birthday dinner that evening was just ourselves and David and Carmel at the Crannog seafood restaurant on the pier. A complete surprise was the birthday cake with candles that Joan had organized beforehand.

The next day was fine and clear and after we’d moved our luggage to the Grange, Joan suggested the gondola to the Nevis Range ski fields might be a nice thing to do. So, we rounded up David and Carmel and drove north out of town to the visitor centre and caught the gondola up the side of Aonach Mor, the eighth highest mountain in Britain. A succession of mountain bikers scooted down the tracks on the hill beneath us as we ascended and when we got to the top the views to the west were absolutely spectacular. David and I took the 30-minute walk to the rocky outcrop called Meall Beag where in the foreground you could see Caol and Banavie on the northern end of Loch Linnhe and beyond that Loch Eil and the mountains of Moidart. You could even just see the Hebridean island of Eigg in the far distance. And over our left shoulder, the bulk of Ben Nevis.

The way back to Fort William took us past the driveway entrance to the Inverlochy Castle Hotel. Joan had told us they did an afternoon tea, so we thought we’d try our luck. Built by the English Baron Abinger (Eton; Trinity College, Cambridge; Scots Guards) in 1863, it’s a Victorian baronial mansion that’s been a hotel since 1969. The dining room was full of ladies of the type that looked down their nose at you, so we had a cup of tea in the main reception hall while Carmel slipped into reveries about Outlander. Just time to go back for a freshen up and then we piled into a taxi to the Smiddy at Spean Bridge for another slap up dinner courtesy of the wicked maître d’ Robert and chef Russell. The scallops and Stornoway black pudding entrée was the best dish I had on the trip. The rest wasn’t bad either.

The next day was Sunday. A cruise ship, the MV Astoria, had come in during the night and was moored just off the pier. Unfortunately for the passengers, the rain had set in and you could hardly see across Loch Linnhe. We motored south out of town to meet my Kinlochleven cousin Alan and his wife Janice for lunch at The Corran restaurant at the Corran Ferry, which is half way between Kinlochleven and Fort William. The ferry across Loch Linnhe—the busiest single route ferry link in Scotland—connects the A82 just north of Onich with the A861 at Corran and the areas of Ardgour, Kingairloch, Sunart and the unspoiled Ardnamurachan peninsula, the most westerly point of mainland Britain. The Lochaber Times had a story about the future options for the ferry, with the Scottish Government reportedly considering the introduction of a bridge to replace it at the Corran Narrows.

Alan had just taken over management of an amateur youth football team based in Kinlochleven and the previous day they’d all driven down to Giffnock south of Glasgow for a cup tie. They won and so it was a happy trip back north. A huge Celtic fan, he said he and his son Alan (who works as a chef in Fife) had bought a season ticket that they planned to share during the season. That’s dedication. And they both absolutely love Celtic Socceroo Tommy Rogic.

After a pleasant lunch, we drove back to Fort William and up the hill to Blarmachfoldach to pay our respects to Joan’s mum, my auntie Margaret. In the 19th century the area supported a crofting community of over eight hundred. After the Highland Clearances only a handful of people remained. These days there are many more black-faced sheep than people. It’s a lovely, but lonely spot.

To round off a very family-focussed day, Joan made dinner for us, and invited Carmel and David too.

Elgin

Monday and it was my birthday. Sixty-five seemed so old when I was younger. It doesn’t seem quite so old now. Well, maybe sometimes.

For years I had hankered to see Glen Affric, reputedly the most beautiful glen in Scotland. It lies to the west of Loch Ness and runs deep to the south-west in the direction of Glen Sheil and the road to Skye that leads past Eilean Donan Castle. The weather was reasonable and as a special birthday treat, Di agreed to drive me there.

We picked up a map and guide at Drumnadrochit and headed for Cannich at the entrance to the glen. It was not what I expected. Used to the stark, rugged grandeur of Glencoe and Glen Nevis, this was quite a different beast. Trees everywhere. In the valley and up the sides of the hills. Various places to stop, park and go for walks in the forest—for it does contain the best-preserved areas of the ancient Caledonian forest. We weren’t dressed for forest walks, so drove to the end of the single-track road. A short climb up through the heather and bracken to the An Meallan viewpoint was rewarded by a beautiful vista looking south west to a ribbon of loch framed by a succession of misty hills receding into the distance (see main image). Bucket list—tick.

One slightly jarring note in the guide was that the Chisholm clan, which had owned the glen since the 15th century, had evicted their tenant famers in the early 1800s during the Highland Clearances. In a pattern repeated across the Highlands, the glen then became a sporting estate.

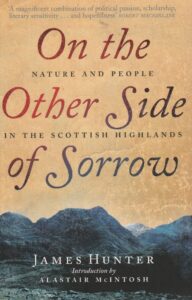

The combination of spectacular natural beauty with rich, often sorrowful history is what gives the Highlands its allure. The most famous is Glencoe, universally known as the ‘glen of weeping’ in remembrance of the massacre of the MacDonalds there in 1692. The book I had brought with me to read on the trip was On the Other Side of Sorrow by James Hunter, subtitled Nature and People in the Scottish Highlands. Drawing deeply on the language and history of the Highlands, Hunter examines the clash between the needs of the community who live or want to live in the Highland environment and the desires of nature lovers and conservationists, whose ideals are grounded in the romantic notions of the Highlands—wild nature suffused in melancholy, with glimpses of tartan-tinged ghosts in the gloaming—created by Sir Walter Scott and others in the 19th century.

The combination of spectacular natural beauty with rich, often sorrowful history is what gives the Highlands its allure. The most famous is Glencoe, universally known as the ‘glen of weeping’ in remembrance of the massacre of the MacDonalds there in 1692. The book I had brought with me to read on the trip was On the Other Side of Sorrow by James Hunter, subtitled Nature and People in the Scottish Highlands. Drawing deeply on the language and history of the Highlands, Hunter examines the clash between the needs of the community who live or want to live in the Highland environment and the desires of nature lovers and conservationists, whose ideals are grounded in the romantic notions of the Highlands—wild nature suffused in melancholy, with glimpses of tartan-tinged ghosts in the gloaming—created by Sir Walter Scott and others in the 19th century.

He describes the reaction of the Canadian writer Hugh MacLennan, descended from Scottish emigrants, on his first visit to Glen Shiel, just the other side of the Five Sisters of Kintail range from Glen Affric. ‘Above the sixtieth parallel in Canada you feel that nobody but God has ever been there before you, but in a deserted Highland glen you feel that everyone who ever mattered is dead and gone.’

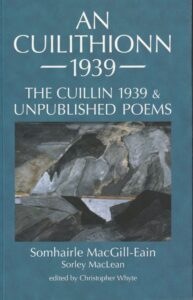

The title of Hunter’s book comes from Sorley MacLean’s epic 1939 Gaelic poem ‘An Cuilithionn (The Cuillin)’, a poem about the clearances. In MacLean’s own English translation, it concludes:

Beyond the lakes of blood of the sons of men

beyond the frailty of the plain and the labour of the mountain

beyond poverty, consumption, fever, agony,

beyond hardship, wrong, tyranny, distress,

beyond guilt and defilement, watchful,

heroic, the Cuillin is seen

rising on the other side of sorrow.

Sorley MacLean was born in Raasay, which nestles up to the east coast of Skye and is separated from the mainland at Wester Ross by the deep Inner Sound. A native Gaelic speaker, he went to Edinburgh University then returned to the Western Highlands as a schoolmaster at Portree on Skye and Tobermory on Mull, where he wrote most of his important poems.

Written in 1939 as Europe teetered on the brink of war, ‘An Cuilithionn’ is at its core about the Highland Clearances. MacLean had left Skye in 1937 to teach in Mull, ancestral home of the MacLeans. Mull in 1938 made him ‘obsessed with the Clearances’, he said.

‘Now Mull, leaving Skye and going to Mull, was a kind of traumatic experience for me too, because Mull—of course the Clearances are written all over Mull—Mull I found a beautiful place, I liked it, but in many ways, I considered it, and still consider it, a heart-breaking place, especially to a man with a sentimental attachment of having the name MacLean, which of course was the greatest of the Mull names. I remember going about Mull on a bicycle and asking a postman somewhere near Ulva Ferry, “is it a Mull man lives on that farm?” meaning a man of genuine Mull stock, “or this one, or that one?” He said “No.” And then asking him, “Can you think of any farm in the north of Mull (there were no crofters then) at which there is a Mull man?” And he said, “No.”’

But ‘An Cuilithionn’ is so much more than ‘Will ye no come back again?’ In an extended tour de force of 1638 lines it weaves the tapestry of history—not just the history of Skye, but of Scotland, Europe and world revolution—into the sgurrs, ridges, corries and bogs of Skye’s spectacular mountain range, the Cuillin.

Poet, songwriter, folk song collector and academic Hamish Henderson said Sorley MacLean was by general consent the best Gaelic poet since the 18th century. He called ‘An Cuilithionn’ Maclean’s greatest poem, saying it ‘ … not only evokes with splendid verve the heroic landscape of the Hebrides, but also makes it a symbol of man’s achievement in shaping his own destiny. The indomitable spirit of the great revolutionaries, Lenin, Liebknecht, Dimitrov and John Maclean is found in “heights beyond thought on the mountains”, among the chasms and pinnacles of the proud sierra … All around them is the eternal sea-surge of human struggle, made stone in the ramparts of the Cuillins.’

Poet, songwriter, folk song collector and academic Hamish Henderson said Sorley MacLean was by general consent the best Gaelic poet since the 18th century. He called ‘An Cuilithionn’ Maclean’s greatest poem, saying it ‘ … not only evokes with splendid verve the heroic landscape of the Hebrides, but also makes it a symbol of man’s achievement in shaping his own destiny. The indomitable spirit of the great revolutionaries, Lenin, Liebknecht, Dimitrov and John Maclean is found in “heights beyond thought on the mountains”, among the chasms and pinnacles of the proud sierra … All around them is the eternal sea-surge of human struggle, made stone in the ramparts of the Cuillins.’

And Sorley Maclean’s poem about the Clan Maclean, ‘Clann Ghill-Eain’, suggested a punch line for a song to Henderson. In it, he refers first to those of his clan who died resisting the Cromwellian invasion of Scotland in the 17th century. Then to a Socialist thinker, man of action and martyr of the First World War period. The English translation goes:

Not they who died

in the hauteur of Inverkeithing,

in spite of valour and pride,

the high head of our story;

but he that was in Glasgow

the battle-post of the poor

great John Maclean

the top and hem of our story.

‘Great John Maclean has come home to the Clyde’ is the punch line of Henderson’s ‘John Maclean March’, recorded by among others, The Clutha (1971), Dick Gaughan (1972), The McCluskey Brothers (1986), The Laggan (2003) and still sung on the streets and pubs of Scotland today. And the wellspring of my own fascination with John Maclean.

But back to my 65th birthday. We drove out of Glen Affric, through Cannich and headed north through Strathglass to the lovely little town of Beauly. We had lunch at a terrific little deli, The Corner on the Square, then popped into The Old School gift shop where I treated myself to the birthday present of Runrig’s 50 Great Songs. And they are. Great, that is.

On to Muir of Ord, then a hard right across the south of the Black Isle to join up with the A9 which took us across the bridge that separates Beauly Firth from the Moray Firth. Skirting the north of Inverness, we found the familiar A96 and motored on down the road to Elgin.

We were staying at the Mansion House, a grand edifice between the tree-shaded Lossie River on one side and on the other, just one street away, a 24-hour Tesco supermarket. The hotel had fallen on hard times this year. The owners went into receivership and the establishment was limping along on a bed and breakfast basis while the new owners worked out how to refresh and reopen its other services (pool, gym, dining room etc.). Perhaps with people being wary because of the place’s well-publicised troubles, somehow we lucked out, getting a room with a king-sized four poster bed and a bay window that overlooked the extensive open grounds.

We just had time to check in, get settled when my cousin Jan and husband Sandy arrived to take us to the mystery venue. Out of town and down the road to Rothes and then on to Aberlour where the party had assembled at the Mash Tun, a restaurant/pub just off the High Street and right on the River Spey. My cousin Roddy had organised the night and the lovely surprise was the presence of my cousin Graham Fyfe and his wife Margaret who had driven 70 miles from Ellon, north of Aberdeen, to be there. I had not seen Graham since my first return to Scotland in 1975, although we did have a long phone conversation in recent years when he was visiting Melbourne as part of his work in the oil industry.

Although I’d be hard pressed to remember all the details, it turned into one of those special nights in a great place in the heart of the Highlands, with nice food, nice drink and great conversation all around the table. Just me and Di, three of my cousins and their lovely partners—but a real gathering of the clan. I think I even got some presents.