Seasons of change: the Adelaide music scene in the 70s

Australia has always been an accurate mirror of the world’s music scene, reflecting and balancing US and UK trends and styles. As the most typical Australian city, Adelaide going into the 1970s provided a fascinating microcosm of the state of play in world music.

The emergence of the rock album as an artform in its own right, a process started by the Beatles with Revolver and Rubber Soul in the mid-sixties, had splintered the music scene into two distinct camps. On the one hand the singles chart was full of simple, superficial pop, typified by the faceless production-line sounds of bands like Brotherhood of Man, New Dream and Edison Lighthouse. On the other hand the album charts were full of the hits of the late sixties ‘underground’ movement.

This movement was itself divided. The British based blues-rock phenomenon was turning into heavy metal while the American West Coast was pumping out gentle strains of introspective folk music.

Inspired by the prevailing credo of peace and love, South Australia’s two pop festivals of the period provided a good illustration of these twin influences. Myponga, held in January 1971, featured the very metallic Black Sabbath, while Meadows, held the next year, had American folkie Tom Paxton and Welsh songbird Mary Hopkin as its overseas draws.

A logical consequence of the marathon twelve-hour Blues Festivals at venues like the Glenelg Town Hall, promoted by Twin St entrepreneur Alex Innocenti, the Myponga Festival was South Australia’s Little Woodstock. The undoubted stars of the event were Daddy Cool, whose infectious fifties-style rock raised even the most beer-sozzled and sun-stricken members of the audience to joyous dancing.

In much the same way as the UK’s Mungo Jerry, whose music also took off at this time, Daddy Cool’s music was perfect for open air festivals and Myponga provided the spark that lit the career of one of Australia’s best-loved bands of the seventies.

Meadows Technicolor Fair, with spokespersons Jim Keays (ex-Masters Apprentices) and Vince Lovegrove (ex-Valentines) was even more ambitious. ‘We believe the whole thing is a new concept in rock festivals,’ ran the duo’s opening statement in the program. And with street theatre, poets, underground movies and health food stalls, as well as the cream of Australian rock, they weren’t far wrong. ‘Meadows Technicolor Fair is in existence to let you do the things you want to do and see things you want to see and feel as free as you possibly can while you’re there’ was the message. In fact, Mary Hopkin being bottled off-stage by drunken and disappointed Thorpie fans (Billy Thorpe and the Aztecs—who were scheduled, but didn’t appear—had become Australia’s loudest and heaviest blues-rock band) showed that the desired atmosphere of peace, love and understanding didn’t quite hold up to the strain.

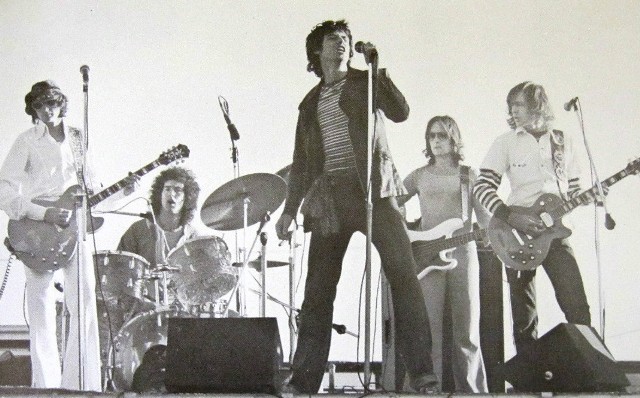

Looking at the program, it’s interesting to see local names like Toads Nightly, featuring a young Martin Armiger (later to find fame, if not fortune, with the Sports), Moonshine Jug and String Band (with Brewster-Neeson-Brewster of the Angels) and Fraternity, at that time fronted by AC/DC”s Bon Scott (pictured at top).

Mary Hopkin being bottled off-stage by drunken and disappointed Thorpie fans showed that the desired atmosphere of peace, love and understanding didn’t quite hold up to the strain

Back in the city, the live scene was thriving. The blues cellars of the late sixties were giving way to the enormous Headquarters (formerly the 20 Plus Club) in Grote St, where on a typical night one might watch Perth’s Bakery support the country’s top two bands, Spectrum and Daddy Cool.

The Largs Pier Hotel came into its own for the first time, while the Pooraka, the Findon and other suburban hotels provided the semblance of a circuit. The two universities, Adelaide and Flinders—both hotbeds of political activism at the time—also provided good venues for bands with their lunch-time concerts and large open air balls throughout the year.

Not much of the music being made in Adelaide in the early seventies made it onto vinyl. Rashamra, featuring the powerful vocals of Andy Peake, were an exception, lobbing two singles Mr Timekeeper and Antelope into the SA Top Five. Fraternity also had some success on the singles chart with If You Got It and Seasons of Change, although a version of the latter by Blackfeather stole their thunder in the eastern states.

Music Express (the band, not the TV show), featuring Tony Faehse on guitar, were a hot act around town, as were Pulse a brassy jazz-blues outfit. Faehse resurfaced later in the decade as a member of Jo Jo Zep & the Falcons, while Steve Ball of Pulse featured in the briefly successful Kush, fronted by out-and-out weirdo Geoff Duff (Duffo).

One of the most influential events of the period was the Deep Purple, Free, Manfred Mann tour in 1971. It should come as no surprise then that when a bunch of young guys climbed on to the back of a flat top truck at the Gawler Raceway to play their first gig in late 1973, there were a number of Free songs in their repertoire. ‘I think the main aspiration back then was to have enough songs to play a gig,’ recalled Don Walker some ten years later. Cold Chisel played Free’s All Right Now and Fire and Water and Ride On Pony. They also did Deep Purple’s Rat Bat Blue, the song that gained Steve Prestwich the drummer’s stool, as the others were impressed by his mastery of the difficult drum figure.

W.G. Berg metamorphosed into Headband and with Chris Bailey singing, enjoyed some national success, both live and with an album, Song for Tooley. Mauri Berg played clean, fluid guitar lines a la Clapton, Peter Head was on keyboards, while Joff Bateman and Bailey held down the rhythm.

Vince Lovegrove, who’d become a mover and shaker around town in addition to fronting a rather radical TV rock show called Move, started managing Cold Chisel, who were practising in the Women’s Electoral Lobby Hall in Bloor Court. Chisel spent 1974 in Armidale, NSW eating magic mushrooms and perfecting their sound while Don Walker completed his university studies. Lovegrove got them into the Largs Pier Hotel and by early 1975 they had the place raging.

Fraternity had meanwhile turned from a Band-influenced style (they used to cover Garth Hudson’s virtuoso Chest Fever from Music From Big Pink) into a harder boogie-style outfit. They spent a fruitless year in London (1972-73) and on their return Bon Scott left and was replaced by John Swan. Then, when drummer John Freeman left, Swanee switched to drums and persuaded his younger brother Jimmy Barnes to leave Cold Chisel and sing with Fraternity, which he did for six months.

An offer was made and accepted and AC/DC went back to Sydney, Bon flew over to join them, they headed for England and from there took over the world.

Bon Scott had a near fatal motorbike accident on Port Road (Note: I have it from a reliable source that the accident Bon had was ‘on a Kwaka 900 in the Rosetta St under pass in West Croydon. He was screaming down Rosetta St and entered the under pass and went straight into the back of a car towing a trailer loaded with milk bottles. A guy in the back of the trailer suffered a broken pelvis and facial injuries. Bon broke about everything …) and when he got out of hospital he used to drive bands from their hotel to the gig, acting as a sometime chauffeur for a local booking agency. One of these visiting bands was a nascent AC/DC, with Malcolm Young and young snotty-nosed brother Angus on the look out for a decent singer. An offer was made and accepted and AC/DC went back to Sydney, Bon flew over to join them, they headed for England and from there took over the world.

Soon after arriving in London with AC/DC, Bon ran into fellow Adelaide musician Graham Bidstrup. Bidstrup had played drums with bands like Fahrenheit 451, Taxi and Pegasus and had decided to check out the London scene. He did a session with Johnny Wakelin, who went on to have two huge hits with Black Superman and In Zaire and had a blow with Lene Lovich and Les Chappell when they were starting out. Bon gave Bidstrup a piece of advice: ‘Go back to Australia. It’s all gonna happen there.’

Bidstrup ran into Chris Bailey in Grapevine Studios in Melbourne St, North Adelaide and the two of them turned up for an audition for an ‘interstate band’ in August 1976. The interstate band was the Angels, having just dropped the ‘Keystone’ from their name and made a fine debut single Am I Ever Gonna See Your Face Again?, produced by living legends Harry Vanda and George Young and released on the Alberts label. Bidstrup was somewhat taken aback, as last time he’d seen the band they were fifties rock revivalists with a residency at the Finsbury Hotel. The lure of success was enough to convince Bidstrup and Bailey however and they packed their bags for late seventies beerbarn boogie (the 1976 line up pictured above).

Cold Chisel (below), with Jimmy Barnes back in the fold, meanwhile moved to Melbourne in the winter of 1976, then up to Sydney where they plied their trade at Chequers and its ilk with other wannabes like Dragon and Rose Tattoo. Through the intervention of music publisher John Brommel they eventually landed a record deal with WEA in late 1977 and released their self-titled debut album in early 1978. The album was adorned with a clutch of Don Walker-penned classics, including Khe Sahn, One Long Day and Home and Broken Hearted.

From November 1974 until mid-1977, Countdown in the Old Mariner Hotel in Hindley St was Adelaide’s biggest venue. In fact, with the buying power of a four night season, the venue was one of the biggest in the whole country. Interstate bands drove in, cleaned up and cleared out, much to the chagrin of local musicians, playing for paltry support band fees. The Lone Star circuit, formed partly to give local bands a better go, ended up repeating the process. Groups like the jazzy Some Dream (which emerged out of Fraternity) and the funky Rum Jungle impressed with their musicianship but seemed unable to break out of the tightly isolated Adelaide scene.

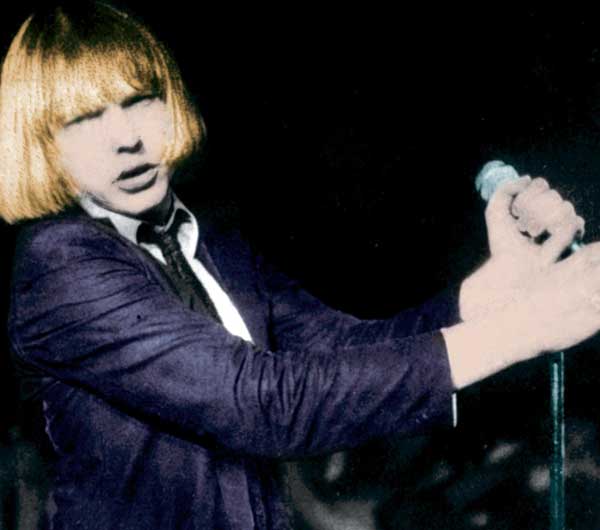

Young Modern blew in like a breath of fresh air. Fronted by the idiosyncratic John Dowler (pictured below), their simple pop songs harked back to sixties innocence but had the stamp of originality and class all over them. Dowler had previously fronted Spare Change, whose album Lonely Suits is one of the undiscovered classics of the seventies. When they broke up in Melbourne, Dowler returned to Adelaide, found a high school band and transfixed them with his vision. They were snapped up by the Sydney-based Dirty Pool agency (run by ex-Adelaide managers and agents) but failed to realise their potential in the hard rock city.

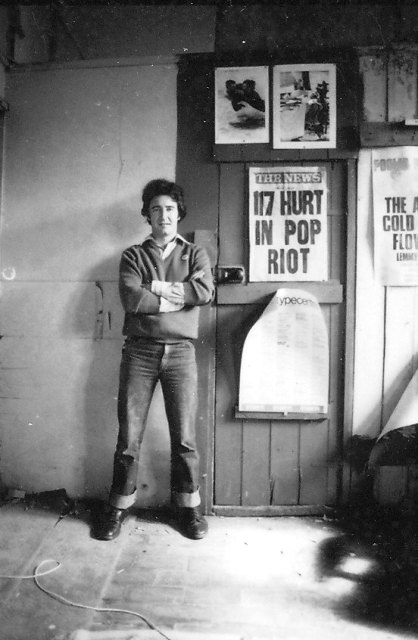

Meanwhile the first signs of the punk rock wave were sighted in Adelaide, particularly in Elizabeth and the northern suburbs—always an early barometer of a coming musical trend. Down at the Seacliff Hotel, Riff Raff were playing credible versions of Sex Pistols faves to bemused surfies and incipient new wavers. At the Belair Hotel, Irving and the U-Bombs were mixing reggae with fast and furious power chords. The Dagoes, a mutant brainchild of various import record store owners, started rehearsing. And up in Elizabeth, the members of what would become the Accountants (pictured below) started learning how to play. They already had the opinions and slogans of the new movement down pat through close study of the UK music press. They had the attitude—all they needed was the music.

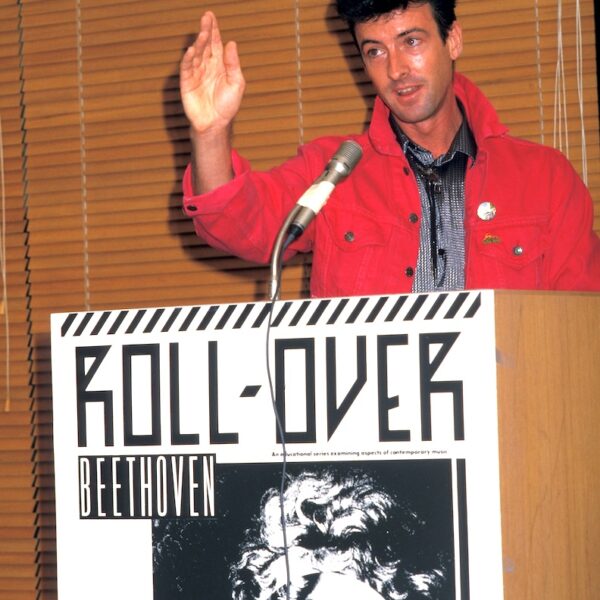

Adelaide also got a new music magazine in this rush of evangelical zeal. The masses must be told about this exciting new music! Local bands must be encouraged to develop! Roadrunner was launched with these twin aims and imbued with the do-it-yourself spirit of the times, much to everyone’s surprise (including the editors) it survived and grew.

Adelaide didn’t turn new wave overnight however and as has always been the case with such an isolated scene, all types of music flourished.

At Flinders University, a classroom project in the Political Sociology Department was starting to bear strange commercial fruit as one of Redgum’s mates at the ABC let them use a studio there. They quickly recorded an album that became Larrikin Records’ best seller and received airplay on most on the non-commercial stations around the country.

If You Don’t Fight You Lose contains one of the best songs ever written about the Festival City, One More Boring Night In Adelaide.

Jazz funk bands eked out a living on the suburban hotel circuit or broke up or drifted off to Melbourne. The most successful, Rum Jungle, gave John James Hackett and James Black to Mondo Rock.

By late 1978, the punk bands had hit the pubs and inspired by the prevailing DIY philosophy started releasing tapes. Live at the Marryatville with the Accountants, the Dagoes and the U-Bombs was the first and to everyone’s shock, it lobbed into the 5KA Progress Chart. It being hard to play punk rock ‘badly’, the tape captures authentically the speed, energy and spirit of punk. A follow-up tape, An Evening With the Dagoes, also did well. It featured an impressive vocal performance from law student Dick Dago as the record store men played their favourite psychedelic riffs from the sixties and early seventies. The result wasn’t bad at all.

Young Modern released a single on their own Top Gear label, She’s Got The Money, produced by Stephen Cummings of the Sports, and promptly moved to Sydney. One of their last shows was a New Year’s Eve Ball for the Progressive Music Broadcasting Association, which had just been awarded an FM radio licence. 5MMM-FM was on its way and it would help to spawn one of the most eventful periods in Adelaide’s music history.

The first of the stations Rock Offs was held in mid-1979. Established to give exposure and encouragement to South Australian talent, these Rock Offs proved popular and constructive for local musicians. The first winners were Terminal Twist, a post-punk outfit playing a strange and quirky strain of pop. They moved to Sydney immediately afterwards, leaving sacked singer Peter Tesla behind, but failed to make any major impression on the Harbour City. Their self-titled/self-financed E.P. was their only tangible legacy.

Jazz funk bands eked out a living on the suburban hotel circuit or broke up or drifted off to Melbourne.

Their heir apparent, Lemmy Caution, were runners-up in that first Rock Off. They took off for Sydney at the earliest opportunity where their catchy economical pop (somewhat reminiscent of Edinburgh’s Rezillos) fell on mainly deafened and uncaring ears.

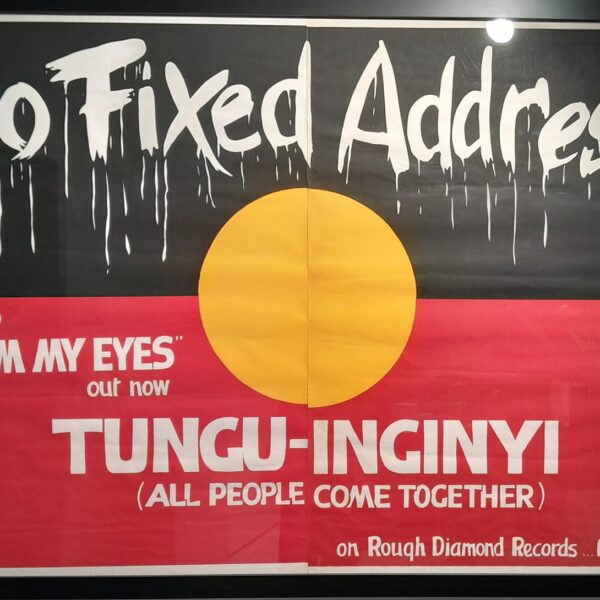

As the seventies drew to a close there was little inkling of the new band explosion that was to turn Adelaide into the most exciting ‘local’ music scene in the country. Within a year bands such as Nuvo Bloc, Systems Go, the Lounge, No Fixed Address, the Bodgies, the Jumpers, Desperate Measures, the Sputniks (who became the Moodists), the Units, the Screaming Believers and others were to dazzle and delight musical enthusiasts with a staggering diversity of musical styles.

It was ironic, but perhaps fitting that an Adelaide band made national headlines on New Year’s Eve 1979, playing in Sydney. One hundred and seventeen fans were hospitalised and two of the Angels were felled by beer cans as a drunken portion of a crowd of over 100,000 at the Opera House surrounds turned nasty.

The Angels and their management stablemates Cold Chisel ended the decade as the undisputed kings of the lucrative Australia pub circuit—their success created in large part by ex-Adelaide agents and promoters. But like their sixties predecessors, the Masters Apprentices, the Twilights and Zoot, they had to go interstate to do it. Adelaide was a great place to get an act together, do a few gigs, write songs and rehearse like crazy. But time and time again, it proved a terrible base from which to crack the rest of the country. Things like image and presentation came low on the scale of priorities in purist music-conscious Adelaide. But those purist qualities stood Adelaide musicians in good stead when they did venture east.

Feature pic: Fraternity 1970

An earlier version of this piece was published as a chapter titled The Seventies, in SA Great It’s Our Music 1956-86, David Day & Tim Parker 1987.

* * *

Playlist: Seasons of Change

Good one Donald! Let me know if you want any pix etc, cheers Tony Faehse

I would love to see any pictures from inside Largs Pier hotel, preferably with either Cold Chisel or Fraternity with Jimmy Barnes. I have plenty of audio but no images.

Hi Mikko – sorry, I don’t have any pictures from inside the Largs Pier. In fact I don’t think I have ever seen any. Cheers, Donald

Thanks for the answer. Sorry I double posted this because did not see my initial posting. I have one of Dave Blight and Mossy playing there. Still, any old photos or sound of Chisel are of interest.

Hi Mikko – no, sorry, I was in the UK 1975-77 when Chisel first formed and started playing.

Love this nostalgia. I worked at 5ka with Vinnie, Daisy, steve Witham, Don Lunn etc. Those were some times.

Just found this site. Brings a lot back. I arrived in Adelaide at the end of 78 after spending most of 1977 in London saturating myself in music. I leave it up to your imagination. I have fond memories of Systems Go, Lounge, Bodgies, the Dagoes in particular. These bands to my mind were the equal of anything the Eastern States produced in that period. Pity there is so little recorded evidence of them.

Many memories of the 1960’s in Adelaide Chris Bailey forming Red Angel Panic.Seeing Blues Rags and Hollers in the Beat Basement in Rundle Street and going to the Oxford Club in King William Street to see The Twilight’s with Glenn Shrrock. Finally The Scene Disco in Pirie Street with the Five Sided circle who are still performing.

I am looking for any old stuff from Cold Chisel during their early Adelaide times.

Great article, thanks for sharing!

There’s a lot of this kind of Adelaide music history recorded on the Adelaide Music Wiki too.

Check it out here:

https://adelaidemusic.wikia.com/wiki/Adelaide_Music_Wiki

A fantastic resource.

I remember Bands like Bullit, Fat Angel, Red Angel Panic, The Harts, Inkase, Octapus and many more what an Era