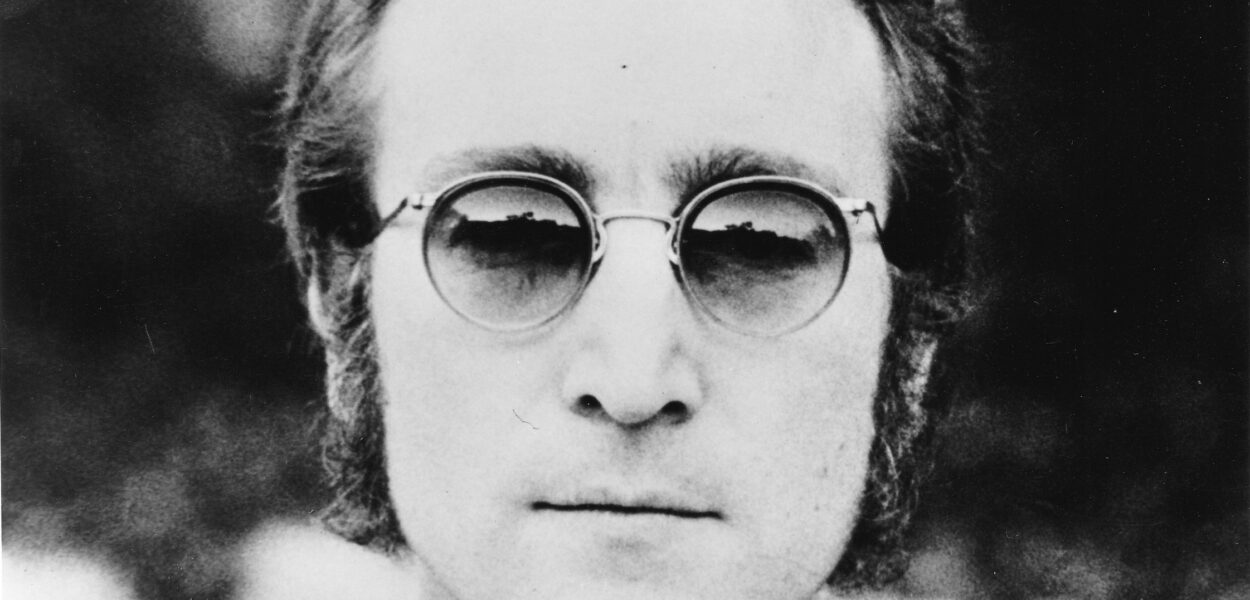

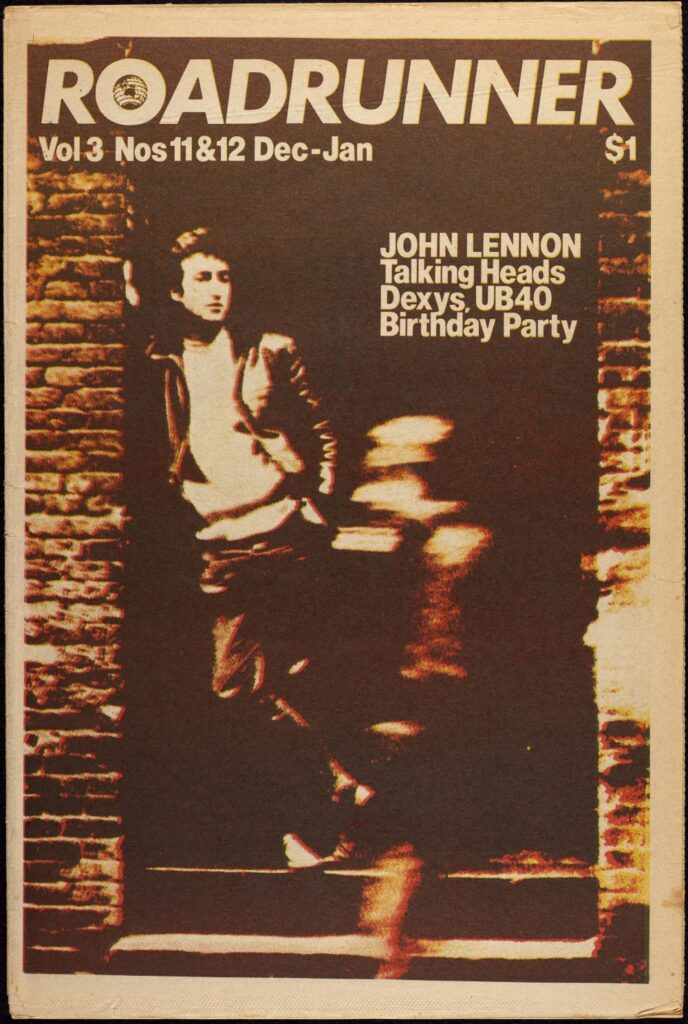

It was mid afternoon on Tuesday 9 December 1980 when the news hit. John Lennon’s been shot. And killed. We were working on the December 1980—January 1981 edition of Roadrunner: Geoffrey Gifford, Richard Turner, Kate Monger and myself. In Geoffrey’s studio up the east end of Rundle Street in Adelaide. We stopped what we were doing of course. And just talked. And after a couple of hours I went home and wrote this. It was the cover story of that edition.

βεατλες

At the inquest on Paul McCartney, aged 21, described as a popular singer and guitarist, P.C. Smith said, in evidence, that he saw one of the accused, Miss Jones, standing waving blood-stained hands shouting ‘I got a bit of his liver.’

—Adrian Henri, from the poem The New ‘Our Times’ (included in the anthology, Penguin Modern Poets 10, The Mersey Sound).

The immortality of the Beatles was shattered by four bullets from a screwball on a New York street a few days ago. All of you reading this will know that already, The Beatles, a full ten years after they went their individual ways still had the power to touch almost everybody and for a few hours the whole western world was united in its shock. The radio and TV blared the news, dailies bannered their headlines, people struggled to come to terms with what had happened, not a few shed tears. For however much they protested their humanity, the Beatles were gods. In the mid-sixties John Lennon said that the Beatles were more popular than Jesus, and for a lot of people that statement made perfect sense. Every religion has its high priests and rock’n’roll is no exception.

But as has often been said, the Beatles as a group were greater than their constituent parts. With rare Lennon and McCartney tracks the exception, the solo works of the individual Beatles in the seventies have had nowhere near the impact, inherent power or importance of the group work of the sixties. John Lennon is being mourned more I think for his being an ex-Beatle than his also being an English composer/songwriter living in New York, a husband to Yoko or a father to Julian and Sean.

Any explanation of John Lennon’s career as an artist has to take into account the myth of the Beatles and how Lennon fought to dissociate from it and assert himself, find himself, as an individual. Although he suffered pain and bitterness and misunderstanding, he did achieve it. And it took five years of living the life of a recluse (a ‘househusband’ as he describes it in the excellent and comprehensive interview in Australian Playboy, Jan. ’81) to do it. John Lennon died a happy man I think. The personal tragedy is that the myth got him, in the shape of an obsessed fan, before he could enjoy it.

The Beatles

The Beatles were a four-man revolution. A music and youth revolution that, with a little help from their friends, changed the face of Western culture in the sixties. The NME Book of Rock puts it fairly succinctly:

The importance of Beatles recorded work in the shaping of contemporary rock is incalculable and is approached in significance only by the career of Bob Dylan. By far the best songwriting team in the field, Lennon-McCartney, supported increasingly by Harrison after Revolver, provided basic material for a series of albums monumental in scope, imagination and technical expertise.

Most of the basic production precepts of today came into being as innovations on particular Beatles tracks and it is extremely unlikely that rock, as it is presently commercially structured, will ever again offer the claustrophobic, hot-house urgency of the conditions in which the Beatles made their most revolutionary music.

The Beatles revolution is well documented. Apart from the millions of words and pictures written in the press, there are countless books on the Beatle phenomenon. Some of the most important are Hunter Davies’ authorised biography, The Beatles, recently updated to include the band’s solo careers (Granada paperback); As Time Goes By by Derek Taylor, which basically covers Apple years: The Man Who Gave The Beatles Away by Alan Williams, one of their early managers, which covers the early Liverpool and Hamburg days; and of course, Lennon Remembers—The Rolling Stone Interviews by Jann Wenner, which dates from the early seventies, just after the first Plastic Ono Band album. There’s also the Playboy interview I mentioned earlier with David Sheff.

I won’t attempt a detailed analysis of the Beatles’ career. Everyone has their own feelings about the group and most of the facts and figures are in the books mentioned above. But it’s interesting to get Lennon’s views on the phenomenon, and as most interviewers do tend to concentrate on it, there’s a wealth of opinion.

‘It is impossible to exaggerate Beatlemania because Beatlemania was itself an exaggeration. For those who can’t believe it, every major newspaper in the world has miles of words and pictures in its cuttings library giving blow by blow accounts of what happened when the Beatles descended on their part of the world.’

What was Beatlemania? Hunter Davies in The Beatles:

Beatlemania descended on the British Isles in October 1963.

It didn’t lift for three years, by which time it had covered the whole world. There was perpetual screaming and yeh-yehing from hysterical teenagers of every class and colour, few of whom could hear what was going on for the noise they were making. They became emotionally, mentally or sexually excited. They foamed at the mouth, burst into tears, hurled themselves like lemmings in the direction of the Beatles, or just simply fainted.

Throughout the whole of the three years it was happening somewhere in the world. Each country witnessed the same scenes of mass emotion, scenes which had never been thought possible before and which are unlikely to be repeated.

It is impossible to exaggerate Beatlemania because Beatlemania was itself an exaggeration. For those who can’t believe it, every major newspaper in the world has miles of words and pictures in its cuttings library giving blow by blow accounts of what happened when the Beatles descended on their part of the world.

Once it had stopped, in 1967, and everyone was either overcome by exhaustion or boredom, it was difficult to believe it had all happened. Could everyone have been so mad? People of all ages and intellects eventually succumbed, although perhaps not all as hysterically as the teenagers.

John maintained that that period was when the Beatles died as musicians. In Lennon Remembers—The Rolling Stone Interviews he said:

‘We were just a band who made it very very big, that’s all. Our best work was never recorded.’

‘Why?’

‘Because we were performers … in Liverpool, Hamburg, other dance halls and what we generated was fantastic, where we played straight rock, and there was no-one to touch us in Britain. As soon as we made it, we made it, but the edges were knocked off. Brian put us in suits and all that and we made it very, very big. But we sold out, you know. The music was dead before we even went on the first theatre tour of Britain. We were feeling shit already because we had to reduce an hour or two hours’ playing to twenty minutes and… repeat the same twenty minutes every night. We killed ourselves then to make it . . .’

They made it, but the price was high. Hunter Davies again:

During all the shouting and screaming and boasting of the record breaking tours, in Britain and America, the Beatles were crouching somewhere inside a giant piece of machinery which was transporting them round and round the world. They’d retreated inside it in 1963, forced by all the pressures, and remained there, hermetically sealed.

Earning $1,000 or $10,000 or $100,000 for a one night stand was meaningless. Being rich and powerful and famous enough to enter any door was pointless. They were trapped.

Although they stayed together til 1969, the Beatles seemed to lose something after 1966. The last two ‘Beatlemania’ albums, Revolver and Rubber Soul, are arguably the peak of their career while Sgt Pepper …. is generally considered to be their masterpiece.

John at the time said he realised that ‘None of it is important. It just takes a few people to get going and they con themselves into thinking it’s important. We’re a con as well. We know we’re conning them because we know people want to be conned. They’ve given us the freedom to con them. Let’s stick that in there, we’ll say, that’ll get them puzzling.’

Sgt Pepper … was a collage of nostalgia, reaching back for brass bands, music hall routines and artefacts from the past. The Beatles, and particularly Lennon were really starting to analyse what they were doing. Fuelled by psychedelic drugs they dipped into Eastern religion (leaving George behind when they moved on), movies (although they’d made A Hard Day’s Night and Help earlier, Magical Mystery Tour and Yellow Submarine were actually their own projects), and other projects like Apple. Their manager and guiding figure through the days of Beatlemania, Brian Epstein, died suddenly—and most importantly of all for John, he met Yoko Ono, an avant-garde Japanese artist.

‘The lovable mop-tops became the arrogant leaders of the popocracy. They in turn were absent at the funeral of Swinging London, emerging shortly afterwards as grannie-bespectacled, hirsute, drug-orientated weirdies, just in time for Flower Power.’

It was in that period, 1967-68, that the seeds of John Lennon as John Lennon rather than John Lennon as John Beatle, sprouted. In his fascinating description of the ‘pop arts in Britain’, Revolt Into Style (1968), George Melly put forward his thesis for their continuous success up to that time.

They had from the off, a formidable talent, perhaps genius; but very early on they recognised that in order to be free to exploit it, they would have to spend a great deal of their time in weaving and dodging. They knew that in the pop world, the moment of total universal hysteria is the harbinger of complete rejection. Unwilling to retreat into conventional showbiz, the traditional get-out, they invented their own escape route. What Brian Epstein called their ‘marvellous instinct’ has allowed them to recognise the precise second before the band wagon they were riding plunged into the abyss.

The lovable mop-tops became the arrogant leaders of the popocracy. They in turn were absent at the funeral of Swinging London, emerging shortly afterwards as grannie-bespectacled, hirsute, drug-orientated weirdies, just in time for Flower Power.

But after Sgt Pepper they all jumped on different bandwagons. George got heavily into Eastern music, Paul got into the business side of their career, with projects such as Apple, Ringo hung around getting bored and John—well John got into Yoko, and through her into the avant-garde and peace politics.

Their incredible momentum kept them going until 1970 but it was a sinking ship. Many saw the split as having been caused by Yoko, but John offered his personal explanation in the David Sheff/ Playboy interview:

They (the other Beatles) were so upset about the Yoko period and the fact that I was again becoming as creative and dominating as I had been in the early days, after lying fallow for a couple of years, it upset the applecart. I was awake again and they couldn’t stand it.’

PLAYBOY: Was it Yoko’s inspiration?

LENNON: She inspired all this creation in me.

Yoko was Lennon’s escape route from the Beatles. But although the band broke up, the myth remained and it was to haunt Lennon like for the rest of his life—no matter how he tried to shake it.

∞

‘Let’s talk about mythology, Lobey. Or lets you listen … You remember the legend of the Beatles? You remember the Beatle Ringo left his love even though she treated him tender? He was the one Beatle who did not sing, so the earliest forms of the legend go. After a hard day’s night, he and the rest of the Beatles were torn apart by screaming girls and he and the other Beatles returned, one by one, with the great rock and the great roll.’ I put my head in La Dire’s lap. She went on. ‘Well that myth is a version of a much older story that is not as well known. There are no 45s-or 33s from the time of this story. There are only a few written versions … In the older story Ringo was called Orpheus. He too was torn apart by screaming girls. But the details are different. He lost his love—in this case Eurydice—and she went straight to the great rock and the great roll, where Orpheus had to go to get her back. He went singing, for in this version Orpheus was the greatest singer, instead of the silent one. In Myths things always turn into their opposites as one version supersedes the next.’

I said, ‘How could he get into the great rock and the great roll? That’s all death and all life.’

‘He did.’

‘Did he bring her back?’

‘No.’

—Sam Delany, The Einstein Intersection (1967).

All the Beatles had to live with the myth that was created around them, but Lennon felt it most and tried most fiercely to put it behind him. ‘Don’t believe in Beatles’, he sang on God from the Plastic Ono Band album. ‘Just-believe in me/ Yoko and me/ And that’s reality.’ And that album, written after a period of primal therapy, was full of similar deep soul cleansing songs.

It was followed by the less intense and more commercial Imagine, then the loose rocking of Sometime in New York City. Mind Games and Walls and Bridges were a return to the melodicism of Imagine, but his last album before the present Double Fantasy, Rock’n’Roll was a craftsman-like reworking of some of his favourite fifties songs. It was a superb offering but indicated Lennon had come to a creative dead end. He and Yoko at last had a child, their son Sean, and Lennon vowed to take the next five years away from the ‘merry-go-round’ as he calls it in Watching the Wheels from Double Fantasy, to be with his son.

Do we have to divide the fish and the loaves for the multitudes again? Do we have to get crucified again? Do we have to do the walking on water again because a whole pile of dummies didn’t see it the first time or didn’t believe it when they saw it? No way.

Commenting on that line, ‘Don’t believe in Beatles’ in the Rolling Stone interview, he said:

‘Yeah. I don’t believe in the Beatles, that’s all . . . there’s no other way of saying it, is there? I don’t believe in them whatever they were supposed to be in everyone’s head, including our own heads for a while. It was a dream. I don’t believe in the dream anymore.’

And when the hoary old topic of a Beatles reunion was brought up in the Playboy interview:

‘… I don’t believe in yesterday … Do we have to divide the fish and the loaves for the multitudes again? Do we have to get crucified again? Do we have to do the walking on water again because a whole pile of dummies didn’t see it the first time or didn’t believe it when they saw it? No way. You can never go home. It doesn’t exist.’

Later in the same interview, Lennon put an additional perspective on it:

‘With the Beatles, the records are the point, not the Beatles as individuals.’

And it is the music alone that has any claim to immortality. John Lennon’s deeds, his great work for peace in the late sixties and seventies, his performances, in interviews and on stages, all his work is now in the past. That he left his mark on the world is without doubt. He has left his music to remember him by, but finally the dream, for John, is over.

The myth of the Beatles will outlive all the Beatles. John Lennon will always be a working class hero, even if it was only ‘just something to be’.

Great read Donald! Thanks for sharing.

I will always remember stepping off a bus at Franklin Street Depot in Adelaide after a week long holiday at Normanville with my two boys and staring in stunned silence at the newspaper poster: Lennon Shot Dead.

That image has never left me.